Background on the relationship of overwintering monarch numbers in 2023-2024 to the extreme drought in October and November 2023

Wednesday, February 7th, 2024 at 12:13 pm by Monarch WatchFiled under General | Comments Off on Background on the relationship of overwintering monarch numbers in 2023-2024 to the extreme drought in October and November 2023

The text and graphics below are intended to provide the background needed to understand why many of the monarchs in the 2023 fall migration failed to reach the overwintering sites in central Mexico. This is a story of biology, weather and geography as well as the resource supply chains that support the monarch migration. This is not a scientific analysis. That is underway.

What is the monarch butterfly’s annual cycle?

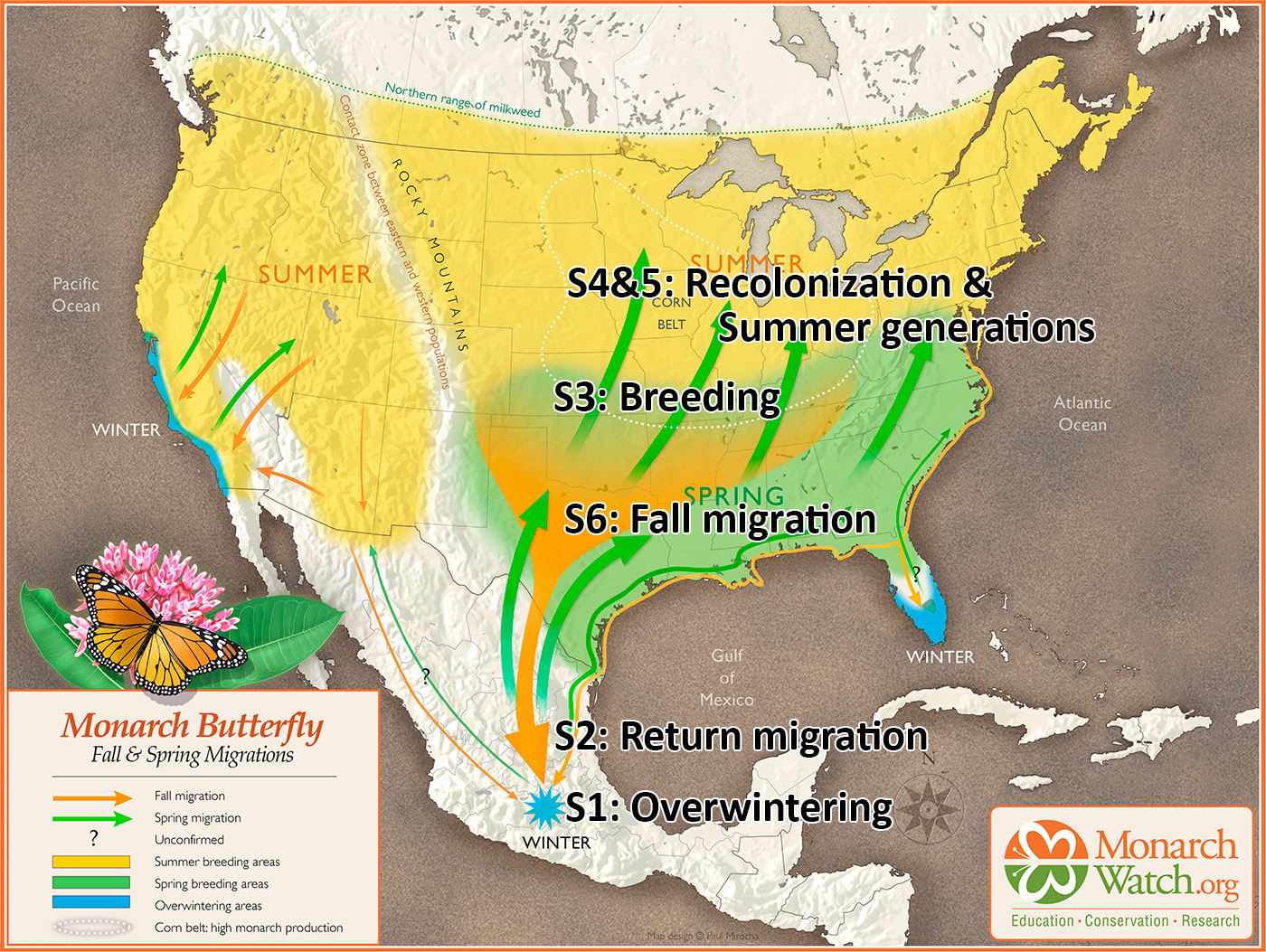

The eastern monarch population overwinters in Mexico. Monarchs that survive the 5month winter begin moving north at the end of February/beginning of March with the leading edge of spring migrants reaching Texas in the second week of March. The returning females lay eggs on native milkweeds through March and April with most dying by the first of May. The offspring of the returning monarchs begin to emerge in late April. These butterflies migrate northward to colonize the northern breeding areas. It is the reproduction in these northern areas, usually two more generations, that produces third and fourth generations that migrate in the fall. The pattern of the north to south movement is represented on the map in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Spring and fall migration map showing stages.

How can you predict monarch overwintering numbers?

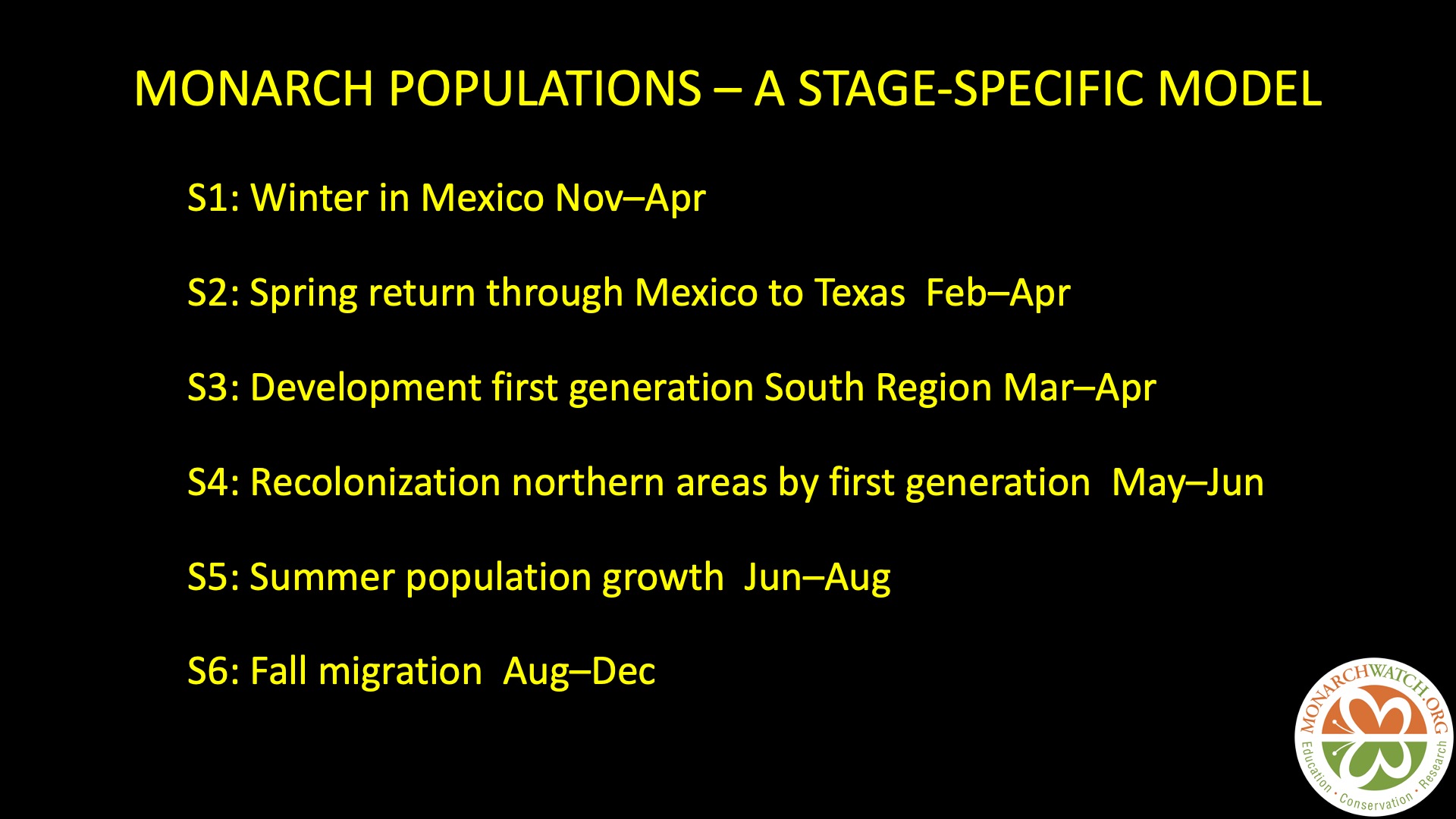

For the purpose of developing a model that predicts overwintering numbers, the annual cycle of monarchs is partitioned into six overlapping stages: 1) overwintering in Mexico from November to April, 2) migrating back to the United States from late February to April, 3) breeding from March to May by returning monarchs, 4) first generation recolonization of the summer breeding areas north of 40N, 5) summer breeding from May to September and 6) migration to the overwintering grounds in Mexico from August to December. The time intervals represented by each stage are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Stages in the annual cycle.

This stage-specific approach represents an attempt to understand/estimate the numbers of adult monarchs at the start of each stage, to define the weather conditions during the stage and to assess how those conditions determine the birth and/or death rates that establish the number of adults entering the next stage. The analysis used to predict whether a population in a specific year will increase or decrease starts with the timing and number of monarchs arriving from Mexico in March (stage 2) and following that the outcomes are compared among years to see if similar metrics result in similar outcomes. 2023 is the most similar to the conditions of 2012, which was the second lowest wintering population (1.19hectares). However, 2023 is different from 2012 because of the drought in Texas in 2023 which suggested even lower numbers in the winter of 2023.

How do weather patterns influence monarch numbers?

Monarch numbers are a function of the weather conditions that determine reproductive success and mortality. Reproductive success itself is determined by the abundance, distribution and quality of host plants (milkweeds) and nectar resources which are also influenced by weather conditions. Predators, parasites and pathogens also limit population growth, and these sources of mortality are also enhanced or limited by weather. The influence of weather on all components in this system allows us to both explain and predict population numbers from one stage to the next. This overall influence of weather tells us that the only way to sustain monarchs is to maintain and restore the milkweed and nectar resources monarchs require. That dictum applies to vulnerable pollinators and insects in general. Given that we can’t change the weather, we must maintain habitats for vulnerable insect species.

How do changing climate trends influence monarch numbers?

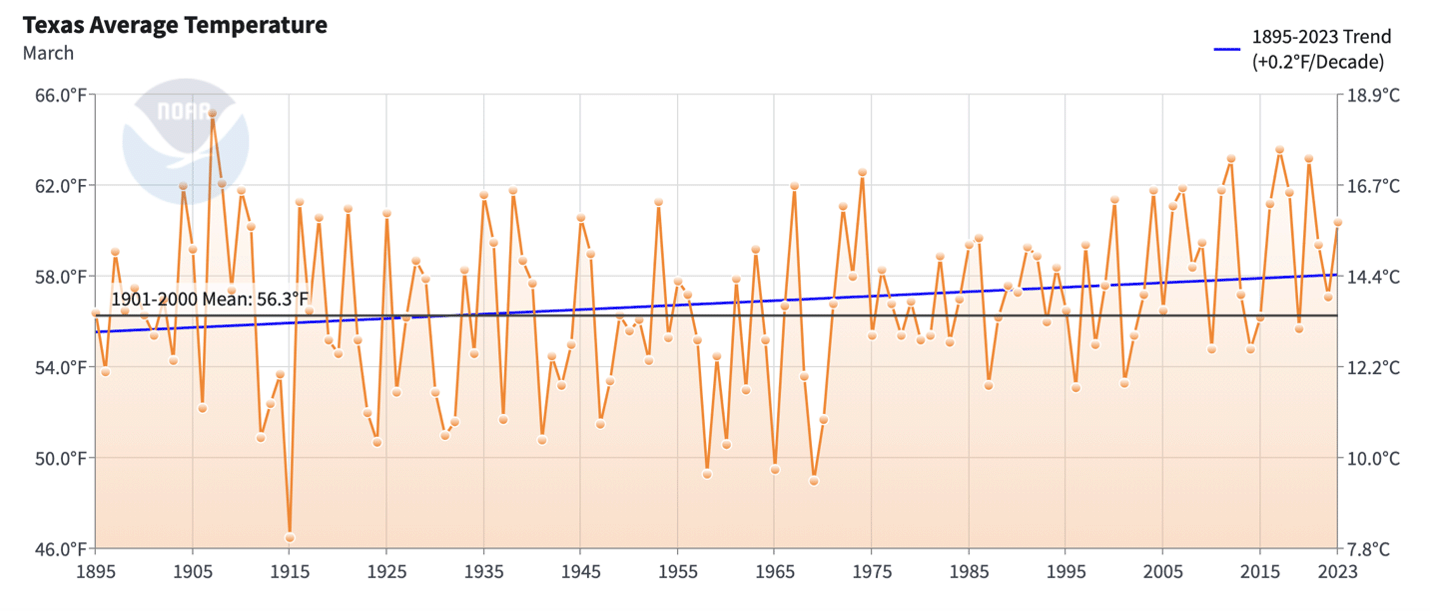

The development of the population each year is strongly influenced by March temperatures. These temperatures determine the timing of the arrival of monarchs in Texas as well as the rate of egg laying and larval development, and therefore, the size of the first generation. These effects follow through the breeding season and usually determine the size of the fall migration. The temperature record for Texas from 1895 to 2023 is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Average March temperatures for Texas from 1895-2023. Climate at a Glance Statewide Time Series

There are three trends in these records: the high variation from year to year that ended around 1974, the damped variation from 1975 to perhaps 1994 and the progressive increase in temperatures from 1994 to the present. The mean temperatures increased during these intervals from 1895-1974 = 56.1, to 1975-1993 = 57.7 and 1994-2023 = 58.6. The recent rate of increase is 1.3F per decade. Note the five periods of 2-3 years in succession with extreme cold March temperatures. Such temperatures delay recolonization by monarchs returning from Mexico and recolonization of the summer breeding area north of 40N. These conditions would have led to smaller migrations and lower numbers overwintering in Mexico.

Why and when do monarchs migrate in the fall?

Tens of millions of monarch butterflies migrate from eastern North America to Mexico each fall to overwinter in the high elevation oyamel fir forests of the Transvolcanic Range of central Mexico. Monarchs are unable to survive freezing temperatures and those breeding in temperate regions must escape to moderate climates to reproduce the next season.

The fall migration begins in early August in the north (Winnipeg) and in September at mid latitudes. The migration progresses at a pace of 25-30 miles per day, although individual butterflies often fly further during periods when conditions are favorable. Because not all monarchs join the migration at the same time and some advance faster than others, it takes the migration 25-30 days to pass through a specific area. Monarchs generally begin arriving at the overwintering sites in Mexico in late October a few days before the Day of the Dead (1-2 November). Most monarchs originate from the Upper Midwest from locations more than 1500 linear miles from the overwintering sites. The duration of the migration appears to be 2-2.5 months but can be longer.

How and when are monarchs counted on the overwintering grounds in Mexico?

The 13 overwintering sanctuaries located within the “Monarch Region” in central Mexico are visited twice per month starting in December. For each colony observed, GPS (global positioning system) coordinates are recorded. The area occupied by each colony is calculated by locating the tree that is farthest up slope and then recording the direction and distance from that tree to the trees around the edge of the colony. The formal report from the authorities includes a table with the size of the colony at each sanctuary. The combined total across all the sanctuaries is reported as the size of the overwintering population. The report from 2022-2023 is available and the most recent report will be posted soon.

2022-2023 Report: Area of forest occupied by the colonies of monarch butterflies in Mexico during the 2022-2023 overwintering period

Why are resource supply chains important?

The monarch annual cycle involves two phases, a period of births and population growth and a period of migration and wintering during which the population declines. Population growth rates are linked to the abundance, distribution and quality of resources and weather. The biological resources in this case involve milkweed host plants for larvae, and nectar for adults that is used to fuel flight and reproduction. In recent decades, it has become apparent that land use and weather largely define the distribution and abundance of the resource base that monarchs require. The intensive use of landscapes has increased fragmentation and eliminated the resources monarchs need. In a word, this is a supply chain problem. There are now big gaps in the resource base and that is limiting population growth (Crone and Schultz, 2022).

During the migration and wintering phase, monarchs are dependent on nectar and water. Nectar provides the sugars that are converted to fats (lipids) that monarchs require during the winter as well as water that is lost due to respiration. During the winter, the fats are broken down into a sugar known as trehalose that is used to fuel metabolic processes. This breakdown releases some “metabolic water”, but the quantities are evidently too low to replace water lost due to respiration, requiring monarchs to seek water sources when the temperatures are high enough for flight.

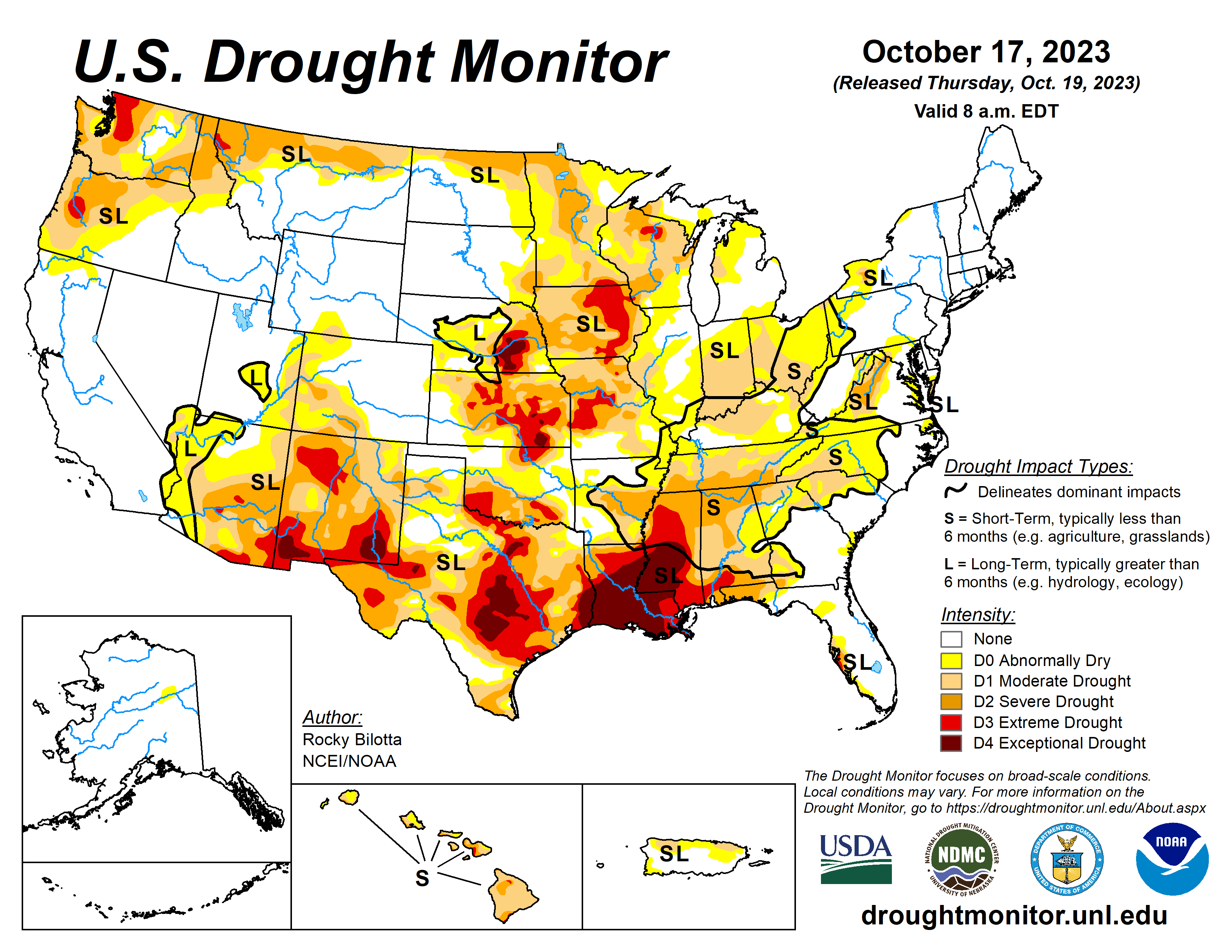

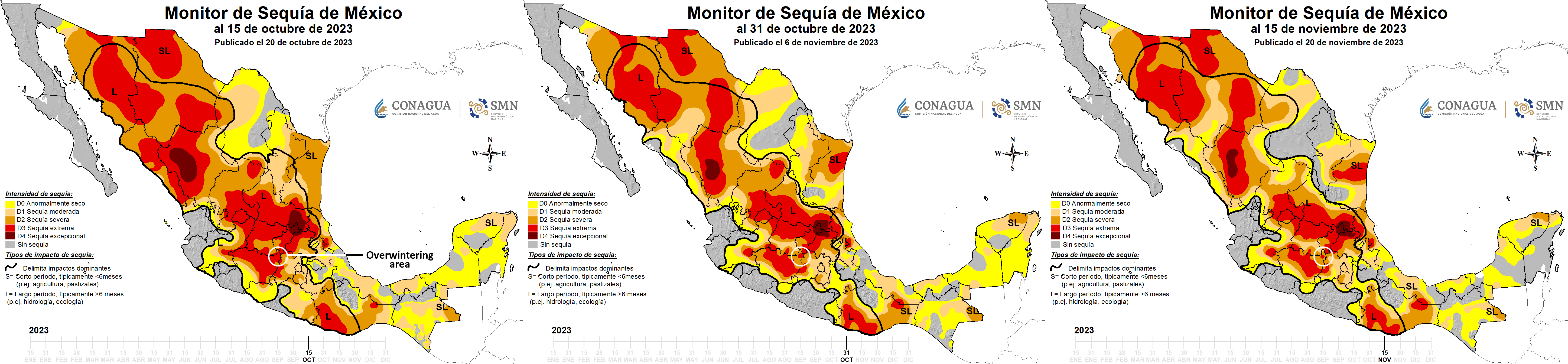

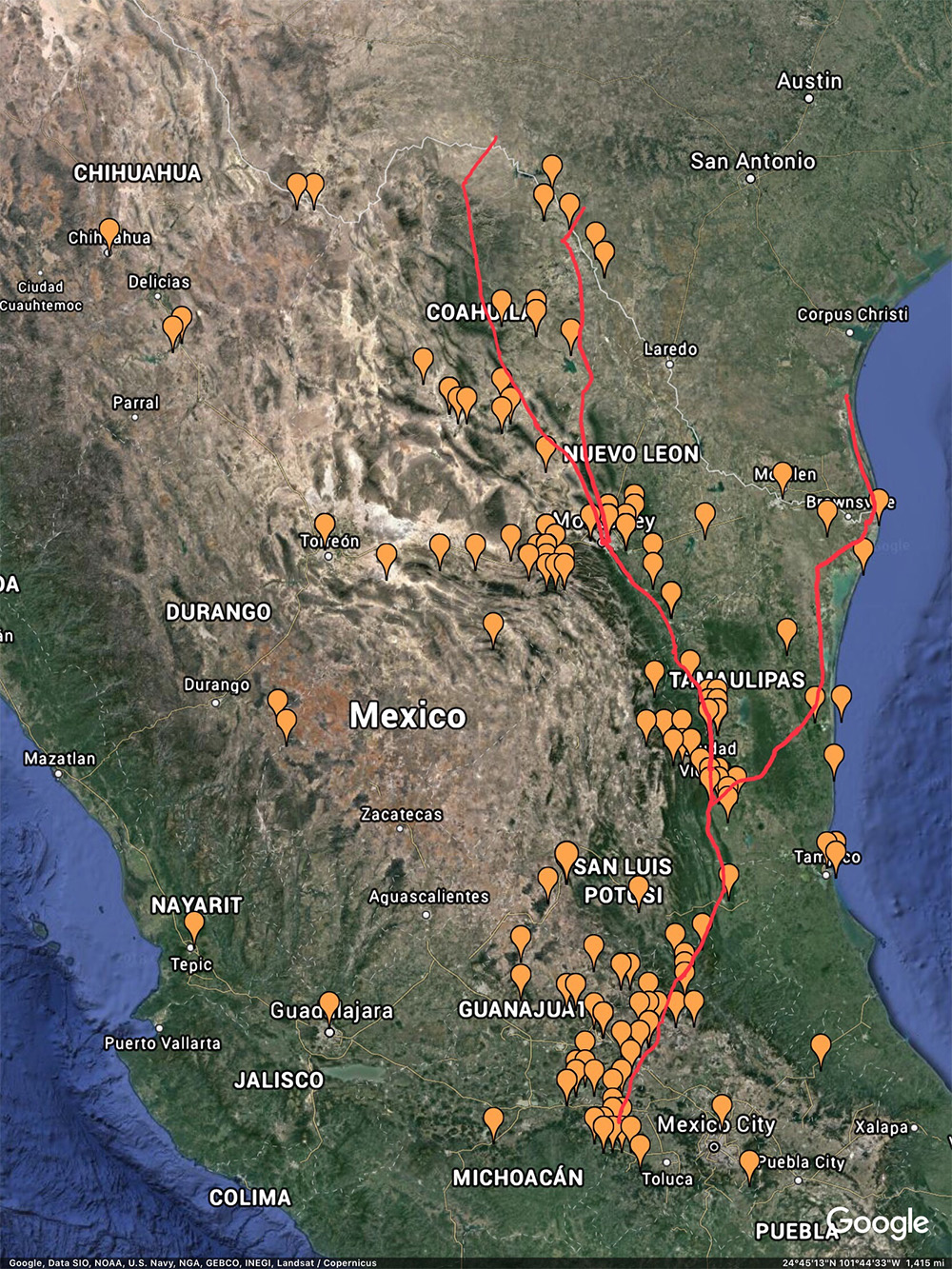

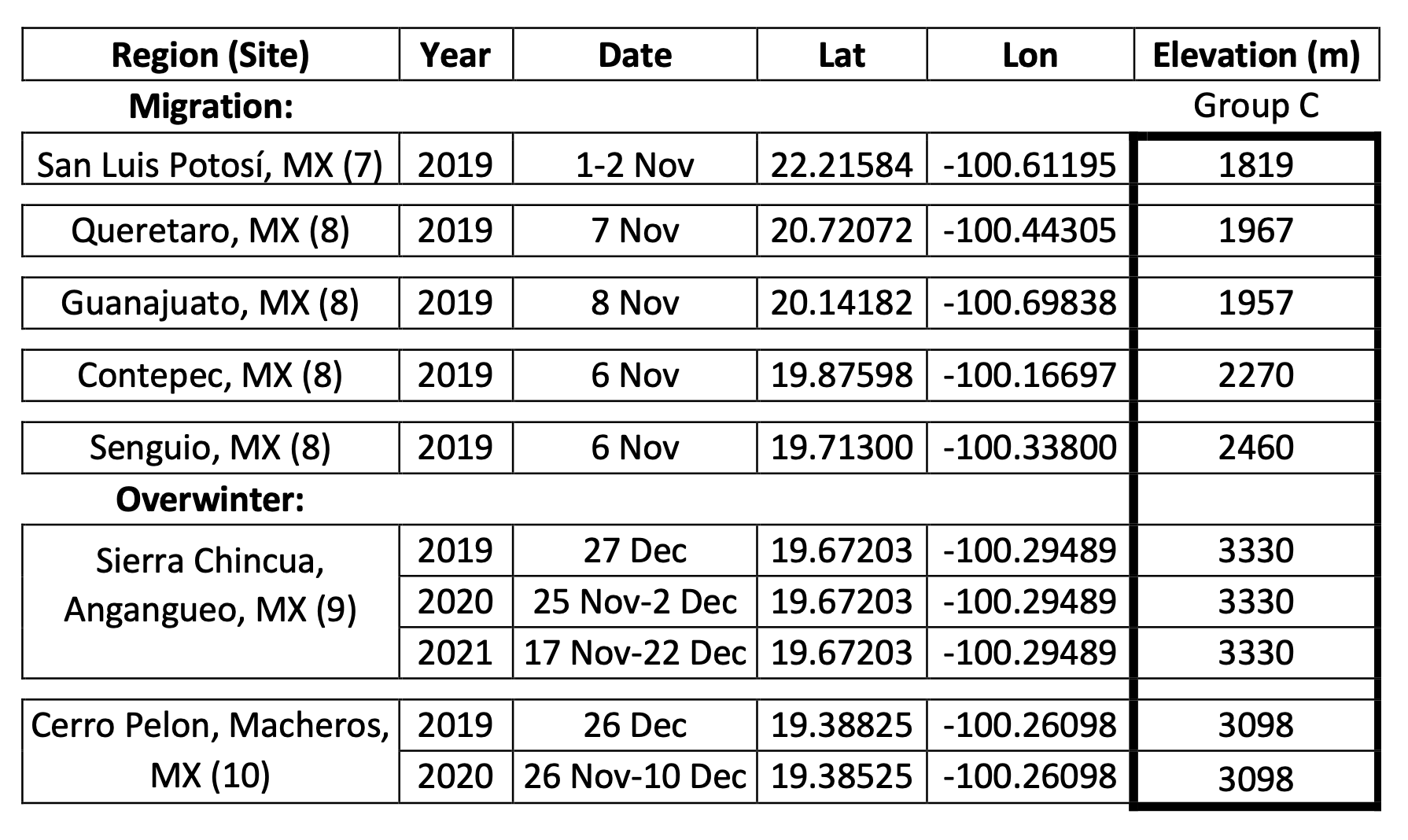

The availability of nectar along the entire migration route is critical. Again, it’s a supply chain problem, a supply chain in the form of fall flowers that is becoming increasingly fragmented. It’s also a supply chain that breaks due to droughts. And it’s the droughts that extended from southern Oklahoma and Texas all the way to the overwintering sites in Mexico that largely account for the low numbers of monarchs that reached the overwintering sites this past fall (Figures 4, 5). Monarchs entering Mexico from Texas in October encountered severe to extreme drought conditions along almost most of the pathway to the overwintering sites (Figure 6). In effect, they encountered a dearth of nectar required to fuel flight and develop fat reserves as well as the water in nectar needed to replace the water lost to respiration. It’s likely these conditions resulted in massive losses as monarchs continued to move south toward the overwintering sites. This interpretation is supported by the results of a recently published paper on the fat (lipid) levels in migratory monarchs from Canada to the overwintering sites (Hobson et al., 2023). There was a drought in Texas in 2019 that extended into northeastern Mexico. The lipid levels were low in monarchs collected in these areas in 2019, but increased and were effectively restored as monarchs passed through the mid-elevation sites in Mexico and approached the overwintering area (Figure 7, Table 1). There was no drought in these mid-elevation areas in 2019. The data from the monarchs reaching the overwintering sites in 2020 and 2021 also indicated that lipid levels had increased from the time they left Texas until they reached the overwintering area. Again, there were no droughts in central Mexico in 2020 and 2021. A conclusion from the Hobson et al., 2023 paper was that “The increase in mass and lipids from those in Texas to the overwintering sites in Mexico indicates that nectar availability in Mexico can compensate for poor conditions experienced further north.” It follows that the absence of nectar in mid-elevation areas in 2023 due to the extreme drought in October and November contributed to the low number of monarchs at the overwintering sites.

Figure 4. This drought monitor map for mid-October shows the extreme and exceptional drought conditions as monarchs migrated through Oklahoma and Texas and into Mexico. Map courtesy of NDMC via U.S. Drought Monitor.

Figure 5. The leading edge of the monarch migration reaches Mexico during the first week of October with some monarchs reaching the overwintering sites by the end of the month. Monarchs continue to arrive at the overwintering sites through the first week of December. The three drought monitor maps from mid-October to mid-November indicate the occurrence of severe and extreme drought conditions along most of the pathway from South Texas to the overwintering sites. Extreme drought characterized the mid-elevation sites that usually are the last source of nectar for monarchs before they reach the overwintering sites. Map courtesy of Mexico Drought Monitor.

Figure 6. Spring first sightings reported for Mexico to Journey North. These records suggest monarchs use two pathways (coastal and inland) to reach the breeding grounds in Texas and beyond. Records and observations suggest that monarchs use the same pathways to return to the overwintering sites in the fall. The coastal pathway is the weaker of the two pathways. In the spring, and sometimes in the fall, the temperatures can be too high and nectar availability too low for easy movement through this area. The inland pathway is longer (about 800miles vs 600miles). Much of this pathway hugs the mid-elevation contours where the temperatures are milder. From January 2023 Monarch Population Status (Taylor, 2023A).

Figure 7. Monarchs were obtained for lipid analysis from these seven marked sites in Mexico in 2019. All samples were obtained along the main fall and spring migratory pathway.

Table 1. The data for the seven sites in Figure 7 – five mid-elevation sites and two overwintering sites in Mexico. (Hobson et al., 2023).

How many monarchs are there in a hectare?

The sizes of overwintering monarch populations are a function of the summation of all the areas of oyamel fir trees occupied by clustered monarchs. The areas are given in hectares (2.47 acres per hectare) with the mean number of monarchs per hectare estimated to be 21.1 million (Thogmartin et al., 2017). Using this estimate, each twentieth of a hectare would be about 1 million monarchs and a tenth of a hectare about 2 million. A million sounds like a large number of monarchs, but it isn’t given the loss that occurs during the winter and return migration. Further, the land area to be recolonized each season is massive. Comparing the first sightings of monarchs reported to Journey North this spring in Texas with the numbers and timing of arrivals over the last 23 years (when Journey North started) will provide out next measure of the status of the population.

What does the low count mean for the future of monarchs?

Unfortunately, the numbers are so low that few monarchs will be seen this coming summer in many parts of the United States and Canada. Several things will be key for developing the largest possible population during the breeding season in 2024. First, a maximum number of the remaining monarchs have to survive the rest of the winter and the return migration to Texas. But there is more, the timing of the monarchs reaching Texas will need to be favorable along with the temperature and precipitation that favor reproduction (Taylor, 2023B).

Despite the low numbers, this count does not signal the end of the eastern monarch migration. Populations have been low in the past, perhaps even lower. Based on what we know about how the monarch population responds to weather, a review of weather records back to 1895 suggests there were several 2-3year periods during which overwintering populations were probably extremely low due to cold temperatures or high temperatures and droughts (Figure 3) (Taylor, 2023C, 2023D).

The bottom line is that the eastern monarch migration is down but not out. Monarchs are resilient and will recover (Taylor, 2023E, 2023F) The pace of the recovery won’t be as fast as the six-fold increase we saw from 2013 to 2015 (0.67ha to 4.01ha), but monarchs will increase (Taylor, 2021). The year-to-year increases will be determined by the weather and the number of milkweeds and nectar plants first in Texas and Oklahoma and then in the northern breeding areas and throughout the rest of the monarch’s breeding range. Monarchs need an abundance of milkweeds and nectar sources, and we need to make that happen for monarchs to recover.

Why do we need to maintain resource supply chains for monarchs?

To sustain the monarch migration, we need maintain the supply chain resources that monarchs depend on during their annual cycle. That means large scale restoration of milkweeds and nectar sources during the breeding season and migration as well as sustaining the integrity of the forests in which they overwinter in Mexico.

What can people do to help?

Monarchs need milkweeds and nectar plants. We need to get more milkweeds and nectar plants in the ground, and we all need to contribute to this effort. There are many resources available to support the creation and management of monarch habitat. For example, you can create or register a Monarch Waystation, and help others do the same. You can also request free milkweed for large-scale restoration projects or for gardens for schools and educational non-profits, or you can order a flat of milkweed plants from our Milkweed Market. Many other organizations have resources and programs to support these efforts, such as the Natural Resources Conservation Service, Farmers for Monarchs, Monarch Joint Venture, the Pollinator Partnership, the Xerces Society, and many more.

People can also contribute to monarch community science projects, such as Journey North. Submitting your first sightings of monarchs to Journey North will help us understand the status of the population this spring. You can also submit monarch nectar plant observations to the Xerces Society. The Monarch Joint Venture maintains a list of community science projects focused on monarchs and milkweeds.

Crone EE, Schultz CB. 2022. Host plant limitation of butterflies in highly fragmented landscapes. Theor Ecol 15, 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-021-00527-5

Hobson KA, Taylor O, Ramírez MI, Carrera-Treviño R, Pleasants J, Bitzer R, Baum KA, Mora Alvarez BX, Kastens J, McNeil JN. 2023. Dynamics of stored lipids in fall migratory monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus): Nectaring in northern Mexico allows recovery from droughts at higher latitudes. Conserv Physiol. 2023 Nov 24;11(1):coad087. https://doi.org/10.1093/conphys/coad087

Taylor OR. 2021. Monarch population crash in 2013. Monarch Watch Blog. https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2021/06/11/monarch-population-crash-in-2013

Taylor, OR. 2023A. Monarch Population Status. Monarch Watch Blog. https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2023/01/04/monarch-population-status-49

Taylor OR. 2023B. Monarch numbers: dynamics of population establishment each spring. Monarch Watch Blog. https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2023/03/27/monarch-numbers-dynamics-of-population-establishment-each-spring

Taylor OR. 2023C. Monarch populations during the dust bowl years. Monarch Watch Blog. https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2023/07/17/monarch-populations-during-the-dust-bowl-years

Taylor OR. 2023D. Monarchs: Weather and population sizes in the past. Monarch Watch Blog. https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2023/07/21/monarchs-weather-and-population-sizes-in-the-past

Taylor OR. 2023E. Why there will always be monarchs. Monarch Watch Blog. https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2023/08/25/why-there-will-always-be-monarchs

Taylor OR. 2023F. Species Status Assessment and the three r’s. Monarch Watch Blog.

https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2023/10/13/species-status-assessment-and-the-three-rs

Thogmartin WE, Diffendorfer JE, López-Hoffman L, Oberhauser K, Pleasants J, Semmens BX, Semmens D, Taylor OR, Wiederholt R. 2017. Density estimates of monarch butterflies overwintering in central Mexico. PeerJ 5:e3221 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3221

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

News reports

Drought in northern Mexico brings water shortages and social unrest

https://dialogochino.net/en/climate-energy/60151-drought-mexico-water-shortage-social-unrest

Mexico in Numbers: Drought

https://mexiconewsdaily.com/news/mexico-in-numbers-drought

Background information on monarch biology

Monarch Watch: Monarch Butterfly Press Materials

https://monarchwatch.org/press

Monarch Watch Blog articles

Taylor OR. 2023. Monarch numbers: trends due to weather and climate. Monarch Watch Blog. https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2023/03/27/monarch-numbers-trends-due-to-weather-and-climate

Taylor OR. 2023. The pending decision: Will monarchs be designated as threatened or endangered? Monarch Watch Blog. https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2023/06/14/the-pending-decision-will-monarchs-be-designated-as-threatened-or-endangered

Other links

Climate at a Glance Statewide Time Series

https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/climate-at-a-glance/statewide/time-series

Farmers for Monarchs

https://farmersformonarchs.org

Journey North: Monarch Migration & Milkweed Phenology Project

https://journeynorth.org/monarchs

Journey North: Monarch Sightings

https://journeynorth.org/sightings

Mexico Drought Monitor

https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/es/climatologia/monitor-de-sequia/monitor-de-sequia-en-mexico

Monarch Watch

https://monarchwatch.org

Monarch Watch: Free Milkweed Programs

https://monarchwatch.org/free-milkweeds

Monarch Watch: Milkweed Market

https://shop.milkweedmarket.org

Monarch Watch: Monarch Waystation Program

https://monarchwatch.org/waystations

Natural Resources Conservation Service: Monarch Butterflies

https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/programs-initiatives/monarch-butterflies

Monarch Joint Venture: Downloads and Links

https://monarchjointventure.org/resources/downloads-and-links

Monarch Joint Venture: Monarch Community Science Opportunities

https://monarchjointventure.org/get-involved/study-monarchs-community-science-opportunities

Pollinator Partnership: Monarch Resources

https://www.pollinator.org/monarch/monarch-resources

U.S. Drought Monitor

https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu

Xerces Society: Monarch butterfly Conservation

https://xerces.org/monarchs

Xerces Society: Monarch Nectar Plant Observations

https://survey123.arcgis.com/share/de1e0d022a4d4732939471cad6969b3a

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.