The pending decision: Will monarchs be designated as threatened or endangered?

Wednesday, June 14th, 2023 at 5:47 pm by Chip TaylorFiled under Monarch Conservation | Comments Off on The pending decision: Will monarchs be designated as threatened or endangered?

Will monarchs be designated as threatened or endangered?

by Chip Taylor

Introduction

As many of you know the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), a division of the Department of the Interior, has been mandated to make a determination as to whether the monarch butterfly should be warranted for protection under provisions of the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The choices seem to be either not warranted or warranted and either threatened or endangered. In a previous ruling in 2020, protection for the monarch was determined to be warranted but precluded on the basis that other species were more deserving of protection at that time. Included in that ruling was a provision to monitor the monarch numbers yearly and to reevaluate the status of the monarch in three years (Taylor, 2020). That time has passed, and the FWS is expected to issue an updated Species Status Assessment (SSA) for monarchs this month.

Because the previous decision was “warranted but precluded” it is probable that “not warranted” is off the table and that the decision will favor either a threatened or endangered status. Realistically, rather than endangered, monarchs are likely to receive a “threatened 4d” designation meaning that monarchs will receive some of the protections and support authorized under the ESA but will not attain the level of protections mandated by endangered status. The threatened 4d status allows for exclusions or exceptions and the overall impact of a 4d determination will be defined by those exclusions (fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/section-4d-rules_0.pdf). The issuance of the SSA will be followed by a public comment period. Following that, a final determination will be made in November, although there is some possibility the announcement could be pushed into 2024.

This pending designation brings forth a number of questions. First, is a threatened or endangered status merited based on the size of the monarch population, its geographic range and the habitat data on hand? In other words, do we have the evidence required to justify such a determination? We can also ask how either designation would benefit monarch conservation. Again, how could our actions, with respect to sustaining and restoring habitat, serve to maintain the monarch migration? That brings us to a matter of scale and investment. How many plants and how many acres would we need to restore each year? It is also fair to ask whether limiting “take” or contact of any kind by citizens with monarchs would be beneficial**.

Endangered vs Threatened

Endangered status is conferred to species that are in danger of extinction in all or in a significant portion of their historical range. Most species receiving this designation are uncommon to rare and have lost a portion of their range or have lost a significant amount of the habitat or resource base that is needed to sustain the population. Rarity can also be due to disease or forms of displacement by introduced species.

The threatened designation is used for species that appear to be likely to become endangered in the future due to declining numbers, a continuous degradation of critical resources in its preferred range or the growing threat of diseases or the introduction of superior competitors. Climate change is another consideration in some cases.

Interestingly, some species designated as endangered have recovered sufficiently to no longer be consider endangered, e.g., giant panda, gray wolf and others. Species once considered to be threatened could also be removed from that status if the original assessment proves to have been overly cautious.

Extinction

As applied in this case, extinction refers to the loss of the monarch migration and not the species per se. Given the link between the increase in greenhouse gas emissions and increasing temperatures and the world’s slow response to these changes, yes, the monarch migration will eventually be lost. The question is when. Is extinction imminent, or likely in the near future? Do we know enough about how monarchs respond to weather variability, and can we predict the course of the changes in climate accurately enough to forecast the demise of the monarch migration? No, we don’t and can’t. Rather, in this instance, due to our lack of certainty, we are applying the “precautionary principal” writ large. Fair enough. But what are the consequences and down-to-earth realities of designating the monarch threatened or endangered?

The Decline

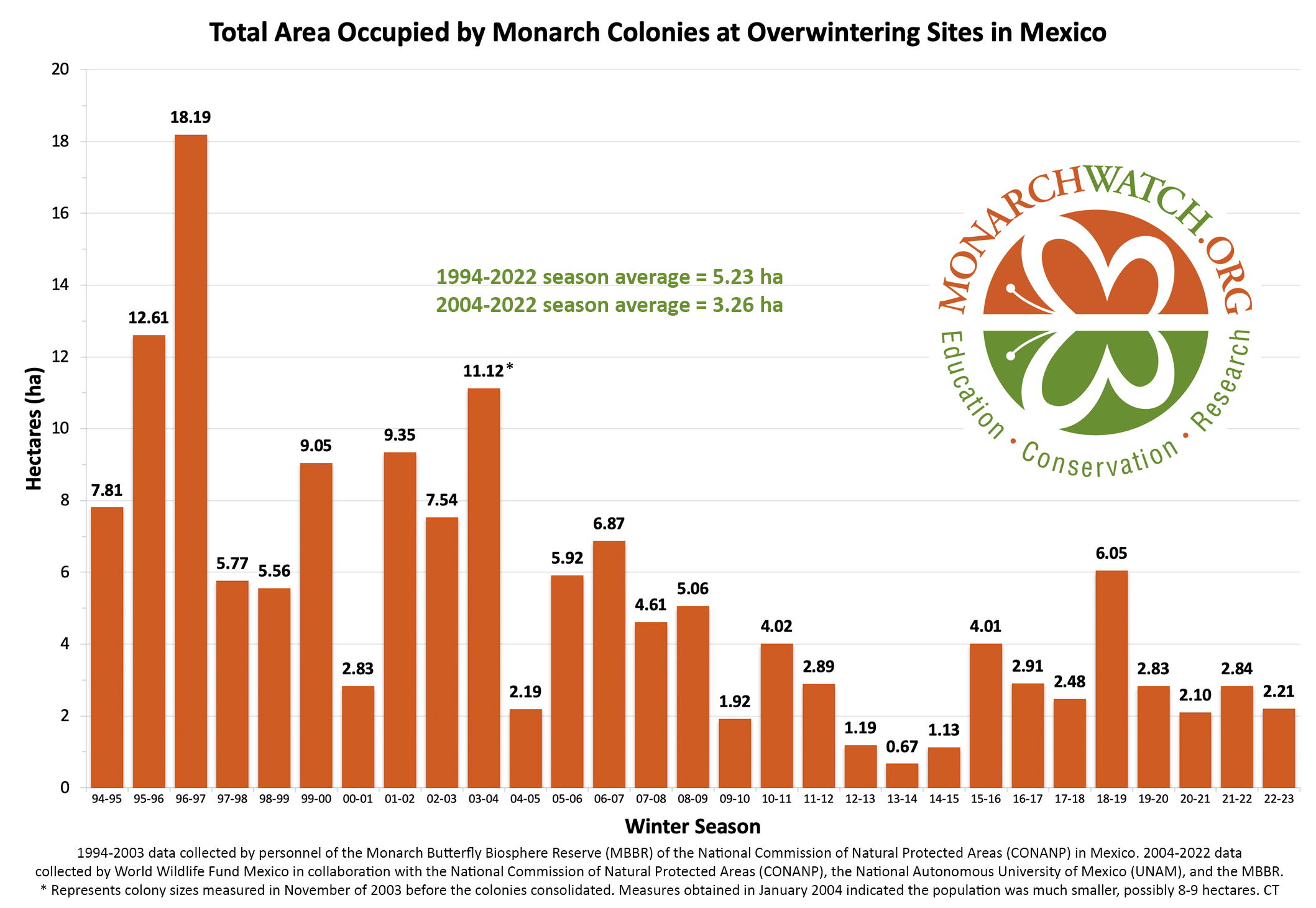

Monarch numbers have declined since the early 1990s. The high population numbers from 1994-1996 are taken as a baseline when the numbers were probably much lower many times in the past. There are no data supporting a supposition that these 1994-1996 populations were “average”. They may well have been the exception. Aside from declines due to specific weather events, e.g., the late spring freeze in 1997 and the drought of 2000, etc., there is ample evidence that the decline was due to the adoption of herbicide tolerant (HT) crop lines (1998 to 2006) (Pleasants, 2017) and the renewable fuel standard (RFS) from 2007-2011 (Lark, et al 2015). In both cases, millions of acres with milkweed that supported monarchs were eliminated from the landscape (Pleasants and Oberhauser, 2012, Pleasants, 2017). There seems to be an assumption that the decline has continued following the end of the surge in corn growing that was spurred by the adoption of the RFS. Perhaps it has, but if so, such effects are too small to be detected given the variability in the annual cycle and the measurements of the colonies in Mexico. Rather, as shown by Meehan and Crossley (2023), there is reason to believe that the monarch population is relatively stable. Further, there is no indication that the population is continuing to decline. One can argue that the population can be expected to continue to fluctuate with overwintering counts varying from .7 to 6hectares within the present climate and amount of available habitat. Under these conditions, running 5-year averages can be expected to vary from 2.5-3.5hectares. Obviously, we need to restore more habitat to improve those numbers.

Status

So, what is the status of the monarch population? How many were there in the Eastern and Western overwintering populations last winter? We also need to know how the populations respond to negative conditions and whether are they capable of rebounding from low numbers?

Abundance

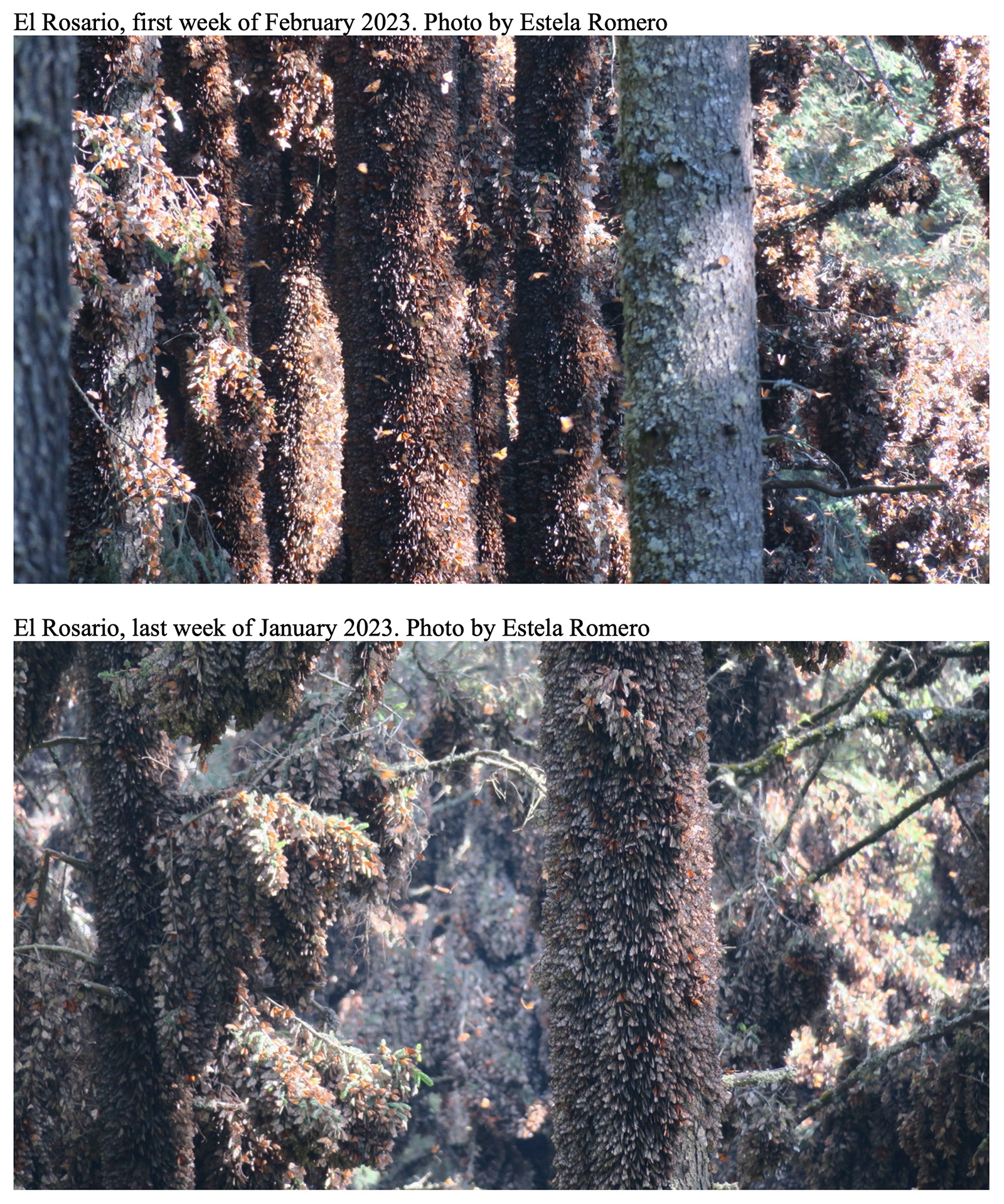

Although the winter count in Mexico of 2.21hectares was 22% lower than the previous year due to weather conditions in the summer breeding range and high temperatures during the migration, the number of butterflies was still substantial. Since there are an estimated 21.1million monarchs per hectare, it follows that roughly 46.6million monarchs overwintered in Mexico this past winter. There have been 6 years in the last 29 during which the overwintering numbers were lower.

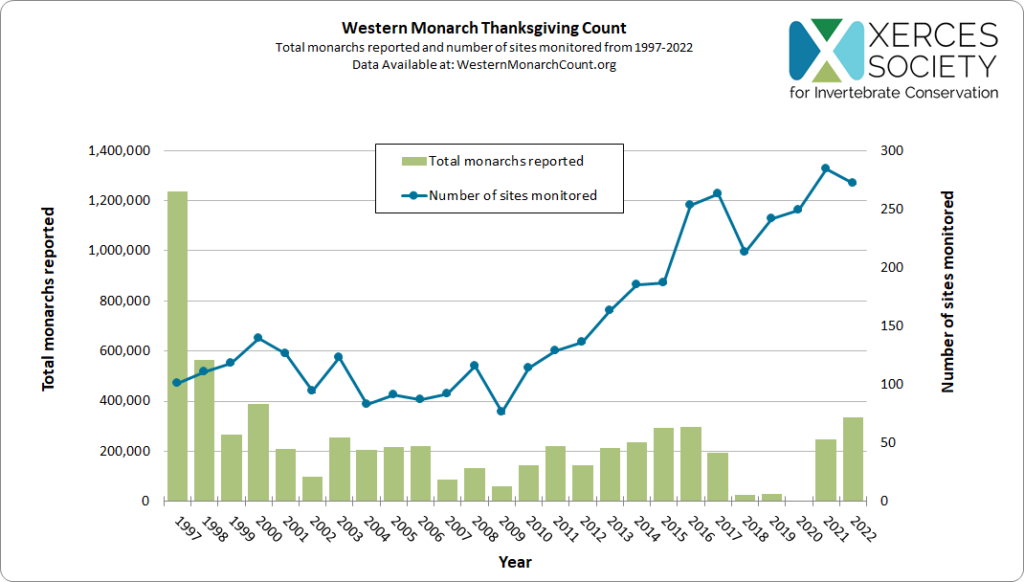

In California, the Thanksgiving counts, coordinated by the Xerces Society, indicated that at least 335 thousand monarchs overwintered at roost sites along the coast from San Diego in the south to Sonoma County in the north. This number was the highest recorded since 2000 (Taylor, 2023C).

Resilience

Have both populations experience lower numbers in the past? The answer is yes.

In the East, the lowest measured number occurred in 2013. During that year, the population measured 0.67hectares. The population increased to 1.13hectares in 2014 and to 4.01hectares in 2015 (Taylor, 2021). The number in 2015 was virtually identical to the number in 2010 (4.02), the year prior to the three-year crash that started with the 7month drought in Texas in 2011. In 2018, five years after the crash, the population measured 6.05hectares, the highest number since 2006.

The overwintering numbers in the West reached an all-time low along the California coast of 1849 monarchs in 2020. Yet, somehow, the population rebounded to 246,253 in 2021, the 8th highest in the last 25 years. The counts increased again in 2022 to 335,479 (Taylor, 2023C).

The recoveries from low numbers in both cases demonstrate the remarkable resilience of this species. Have monarchs recovered from low numbers such as these in the past? Yes, very likely.

The recent collapses are related to weather events, sometimes a series of negative conditions, that reduce reproductive, migratory or overwintering success either separately or in combination (Taylor, et. al. 2020, Taylor, 2023A, B). Using the association of negative conditions to the declines in the last 29 years to the probable success of monarch populations in the past reveals that there have been many episodes in the record during which the populations declined to low numbers. The conditions during the droughts and high temperatures of the “dirty thirties” were much more extreme than any encountered by monarchs in the last 29 years*.

The Choices

Should monarchs be classified as not warranted or warranted but threatened or endangered? The answer depends on whether we are talking near term, that is, the next few decades or look to the future such as 2040 and beyond. In the near term, the population is robust, though not as abundant as in the early 1990s, has maintained the same geographic range and shown itself to be resilient under the current habitat limitations and variation in weather. It is also likely that while monarchs thrived in the early 1990s, and did so from 1975 to 1996, the least variable climate interval from 1885 to the present, their numbers were as low or lower than in recent years many times in the past*. With that perspective, the designation should be “not warranted.”

The long view is different. In time, it will be clear that monarchs are threatened and then endangered. As we all know, the climate is changing, increasing temperatures, along with droughts, both of which are projected to increase in Texas in the coming decades. These changes will progressively limit monarch reproductive and migratory success and, in time, will reduce the ability to overwinter as well. But monarchs will not be alone in suffering the consequences of these changing conditions. Virtually all other species in the United States will be impacted by these changes and many, many other species will be threatened and then endangered. It’s fair to wonder when we will be overwhelmed with trying to protect species from becoming extinct. There is a reality ahead of us that we can’t ignore. We need to be mindful of the rates of change of a multitude of drivers, and we need plans, strategies and resources to cope with these changes. Adaptations will be costly and resources will be limited which will lead to cost/benefit assessments, priorities and triage. At lot of species will be left behind. That already seems to be happening.

So, what is the time frame for the envisioned changes? Do we have a decade, two, maybe three before the monarch migration is lost? We don’t know, but it will happen given the increases in greenhouse gas emissions. So, what should we do? Clearly, we need to maintain and increase monarch habitat, especially in the Upper Midwest, the source area of >80% of the monarchs that overwinter in Mexico (Taylor, et. al., in prep). As to maintaining habitat, we need to know how much habitat is being lost each year in the areas that produce the greatest number of monarchs. And we have to offset those losses with restoration. There are many restoration efforts underway now, but it is not at all clear that restoration is keeping pace with annual rate of habitat loss. Beyond annual losses, the goal is to replace the losses incurred as the result of the adoption of herbicide tolerant crop lines and implementation of the renewable fuel standard. The calculation by experts has been that we need to establish 1.8 billion milkweed stems to attain a monarch population that could sustain a mean of 6hectares of occupied trees at the overwintering sites in Mexico (Thogmartin, et al 2017). There are several difficulties with this projection. First, there is relatively little federal land in the Upper Midwest meaning that the restorations would have to involve marginal lands of tens of thousands of private landowners. That would be a major undertaking. Secondly, that would involve funding – massive funding – since it takes about $2 to establish each new stem. Third, there is neither the seed capacity for wide spread establishment via seeds nor do we have the nursery capacity to produce a sufficient number of plugs (small plants) to meet the restoration targets. And to repeat, those targets are extreme. To reach the 1.8 billion stem goal, we would need to establish at least 100 million stems a year for a decade or more. A hundred million is beyond our capacity to establish stems with seeds or plugs by at least a factor of 10.

Given our limitations, what should our goals be? First, we have to keep pace with the current rate of habitat loss – which is unknown at present – but which could be as much as two million acres per year. Secondly, we will need to do better than to keep pace with habitat losses since there will be losses due to the progressive increases in March temperatures in Texas and the September temperatures in the Upper Midwest and Northeast. Both of these conditions will result in lower numbers of monarchs reaching the overwintering sites (Taylor, et. al., 2020, Taylor, 2023A,B, Culbertson et. al. 2021). That means, that in addition to knowing the mean rates of annual habitat loss, we need to develop a deep understanding of the role of increasing temperatures and droughts on monarch numbers.

What will follow the decision?

Will declaring monarchs threatened or endangered enable us to reach these goals? Will either declaration, along with its associated provisions, lead to more pesticide regulations? If so, would that involve both EPA and the Department of Agriculture? Would such regulations be opposed by organizations that represent farming and ranching interests? Could this become a political issue? These are important questions. The decision by FWS is supposed to be based on science alone, but regulations could trigger a number of issues and conflicts that are independent of monarch biology.

Will the people of the United States be forbidden from all contact with monarchs as is now the case in California? If so, will separating monarchs and the people who care about them increase or decrease the incentives to sustain monarch numbers? Negatives seldom motivate people to do the right thing. Positive incentives that encourage the public to become part of a solution are more effective, but will such incentives be possible if monarchs are declared threatened?

Will a declaration of threatened 4d constitute a threat in itself to land owners who currently have milkweeds on their lands? This possibility seems real since many land owners fear regulations, and along the lines of the “shoot, shovel and shut up” practice that is spoken of in connection with the endangered species act, they might simply eliminate milkweeds from their lands.

More questions involve the possible benefits of a threatened or endangered status. How would either benefit monarchs? Would more money be available for restoration? If so, would the amount be a token relative to the need, and would such funds conflict with the need to protect other species? An initial proposal to sustain and restore monarch habitats could garner support, but the dollar amount would have to be in the 100s of million to mitigate the annual and past habitat losses, and that mitigation would have to be continuous.

While it seems wise to adopt the precautionary principal in the face of threats, we also need to be mindful that all actions along these lines have consequences and it is best “to do no harm”. It’s a delicate balance.

There are many more questions. This is just a start. But here is one more. If the monarch migration will be lost eventually, why make great efforts to sustain it? Faith. We have to have faith that the world will come to its senses and work collaboratively toward the reduction of greenhouse gases to save the natural systems that sustain us. There is hope. The rate of increase in CO2ppm has declined in recent years.

*The data supporting this statement will be posted along with a text describing the known responses of monarchs to temperature extremes.

**The term “take” refers to the impact of human actions on a candidate species and can be intentional or unintentional. Intentional “take” involves any action that would bring harm such as harassing, hunting, collecting, etc. Unintentional “take” would involve incidental harm that occurs as the result of normal activities. For example, you are not allowed to harm a threatened or endangered species, but you would not be at fault if you hit and killed one with your car. Of interest in this case is whether rearing of any sort would be considered “take” and therefore prohibited.

Acknowledgements

Once again, I’m thankful to Janis Lentz for correcting the many things I missed in this draft and to Jim Lovett for assisting with the formatting and posting it to the Blog.

References

Culbertson, K. A., Garland, M. S., Walton, R. K., Zemaitis, L., & Pocius, V. M. (2021). Long‐Term Monitoring Indicates Shifting Fall Migration Timing in Monarch Butterflies (Danaus plexippus). Global Change Biology. doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15957

Lark T.J., Salmon JM, Gibbs HK (2015) Cropland expansion outpaces agricultural and biofuel policies in the United States. Environ Res Lett 10:044003. doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/4/044003

Meehan, T.D. & Crossley, M.S. (2023) Change in monarch winter abundance over the past decade: A Red List perspective. Insect Conservation and Diversity, 1–8. doi.org/10.1111/icad.12646

Pleasants, J.M., and Oberhauser, K.S. (2013). Milkweed loss in agricultural fields because of herbicide use: effect on the monarch butterfly population. Insect Conserv. Divers. 6, 135–144. doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-4598.2012.00196.x

Pleasants, J. (2017) Milkweed restoration in the Midwest for monarch butterfly recovery: estimates of milkweeds lost, milkweeds remaining and milkweeds that must be added to increase the monarch population. Insect Conserv Divers 10 :42–53. doi.org/10.1111/icad.12198

Taylor O.R. Jr, Pleasants J.M., Grundel R., Pecoraro S.D., Lovett J.P. and Ryan A. (2020) Evaluating the Migration Mortality Hypothesis Using Monarch Tagging Data. Front Ecol Evol 8:264. doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.00264

Taylor, O.R. 2020. ESA listing decision for the monarch.

monarchwatch.org/blog/2020/12/15/esa-listing-decision-for-the-monarch

Taylor, O.R. 2021. Monarch population crash in 2013

monarchwatch.org/blog/2021/06/11/monarch-population-crash-in-2013

Taylor, O.R. 2023A. Monarch numbers: dynamics of population establishment each spring. monarchwatch.org/blog/2023/03/27/monarch-numbers-dynamics-of-population-establishment-each-spring

Taylor, O.R. 2023B. Monarch numbers: trends due to weather and climate. monarchwatch.org/blog/2023/03/27/monarch-numbers-trends-due-to-weather-and-climate

Taylor, O.R. 2023C. The Western monarch puzzle: the decline and increase in monarch numbers. monarchwatch.org/blog/2023/05/29/the-western-monarch-puzzle-the-decline-and-increase-in-monarch-numbers

Taylor O.R. Jr, Pleasants J.M., Grundel R., Pecoraro S.D., Lovett J.P., Ryan A., and C. Stenoien. (In prep) Geographic and temporal variation in monarch butterfly migration success.

Thogmartin W.E., Diffendorfer J.E., López-Hoffman L., Oberhauser K., Pleasants J., Semmens B.X., Semmens D., Taylor O.R., Wiederholt R. Density estimates of monarch butterflies overwintering in central Mexico. PeerJ. 2017 Apr 26;5:e3221. doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3221 PMID: 28462031; PMCID: PMC5408724.

Supplementary Materials

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.