Monarch numbers: dynamics of population establishment each spring

Monday, March 27th, 2023 at 5:54 pm by Jim LovettFiled under General | Comments Off on Monarch numbers: dynamics of population establishment each spring

Chip Taylor, Director, Monarch Watch

Introduction

The short narratives that follow describe the outcomes of the timing and number of monarchs arriving from Mexico in March. Each cohort encounters different temperature scenarios in March and April that largely determine the size of the population the following winter season. To be sure, there are additional factors that determine the size of the migratory population and the overwintering number of hectares, but it is largely what happens in March, April and May that set the stage for the rest of the season. A key to population growth is both the number of first-generation offspring produced in this period and their age at first reproduction which is an outcome of their developmental history.

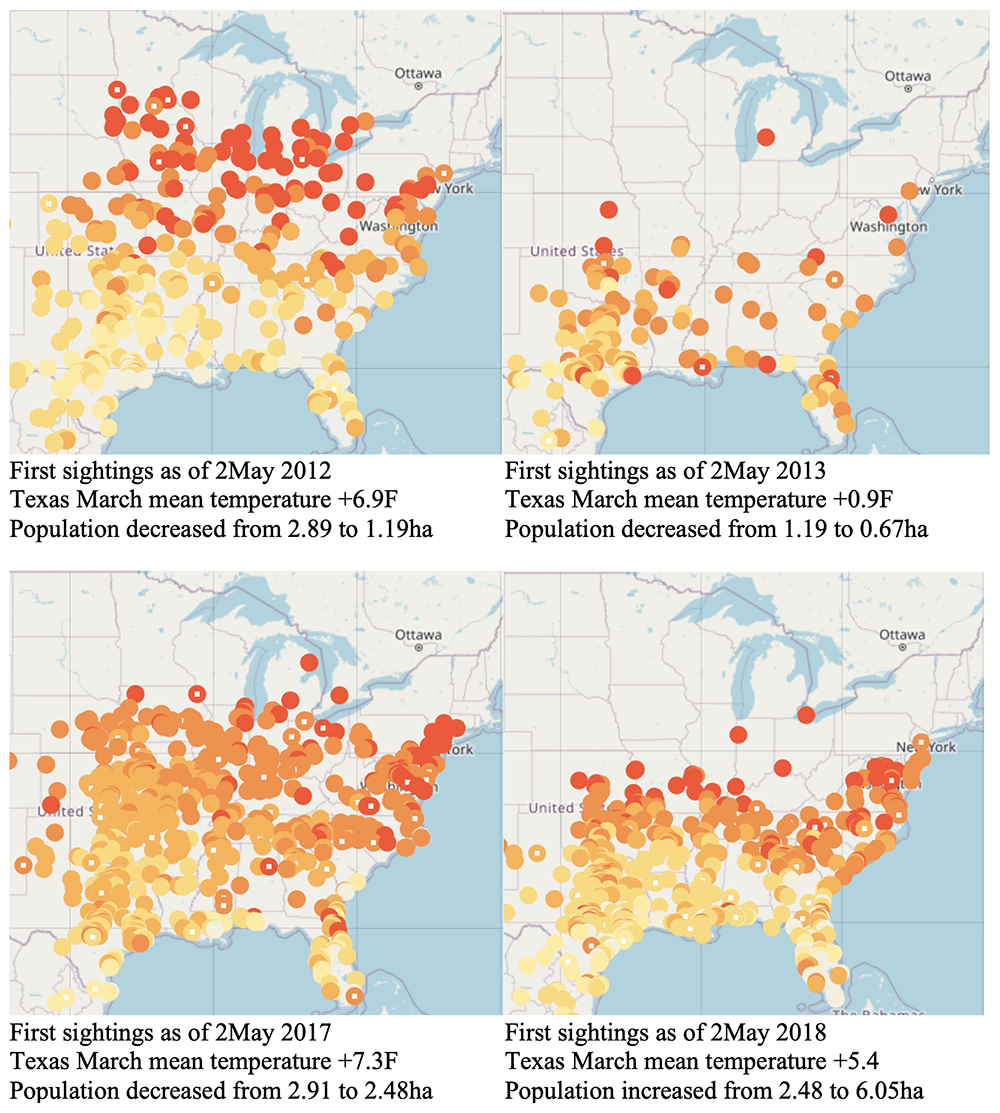

I’ve chosen 4 years – 2012, 2013, 2017, 2018 – to illustrate the dynamics associated with the interactions of the returning migrants and the weather each cohort encounters. The first pair represent both the earliest and most rapidly advancing migration and the smallest and latest cohort to advance north of 40N since 2005. The second pair were selected to show the consequences of advancing northward too soon as in 2017 or being limited to reproducing largely in Texas and southern Oklahoma as in 2018 due to colder weather further north. The latter two show that similar starting conditions can lead to different outcomes. The mean temperatures in March for Texas for three of these years were significantly above the long-term average (+5.4F, +6.9F, +7.3F). Elevated temperatures in this range are expected to become the norm in the near future.

As background, although some monarchs returning from Mexico enter Texas during the first week of March, the influx increases in the second week of March with monarchs often detected in areas of the Edwards Plateau as well as San Antonio, San Angelo and Austin. This progression continues N, NE as weather permits, with most of the returning monarchs dying by the 1st of May. In this analysis, I’ve totaled the first sightings from 30N, just north of the latitude (29N) at which milkweed diversity and abundance increases in Texas, northward beyond north of 40N. The longitudinal range is 80W (western PA) to 100W (mid Dakotas). These progressions each year are related to March and April temperatures for Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas. Throughout this treatment, 40N is used as the southern limit of the summer breeding habitat since tagging indicates that more than 80% of the monarchs reaching the overwintering area originate north of 40N.

2012

March in 2012 was the warmest recorded in the US for that month since record keeping began in 1895. The median arrival for first sighting in Texas was 13March, the earliest in the 24-year record of first sightings reported to and recorded by Journey North. The temperatures were significantly above the long-term averages for March and April from Texas through Kansas (Table 1). These conditions allowed monarchs to advance significantly from Texas into Oklahoma, Kansas and north of 40N by the 2nd of May, with 23% recorded beyond 40N. Overall, this recolonization was the earliest to date for all regions north of 40N with only 3.6% of the sightings reported in the last observation interval from 31May-9June (Table 2, see Appendix). There are significant consequences of advancing northward rapidly; getting ahead of emerging milkweeds and laying eggs in regions which are cooler results in a longer development time for immatures and therefore a delayed age to first reproduction. The latter can have the effect of lowering the rate of population growth. While it is likely that arriving too early at the northern latitudes had a negative effect on population growth, the summer temperatures were also extreme resulting in a substantial drought that also had a negative impact on the development of the generation destined to migrate. Together, these negative spring and summer conditions resulted in a decline in winter numbers from 2.89ha in 2011 to 1.19ha (-1.7ha). These developments were a precursor and likely a contributor to the crash in the population that occurred in 2013.

2013

The number of first sightings in 2013 was low relative to previous and following years, raising the possibility that many monarchs did not survive the winter in Mexico or during the return migration from the overwintering sites to Texas. It is also possible that the weather in Texas limited the activity of the monarchs and therefore the number of sightings. While the mean temperature for March in Texas (0.9F) was close to the long-term mean, the lower April temperatures for Texas through Kansas evidently limited northward movement, with the result that 83% of the first sightings were limited to the 30-35 latitudes (roughly Austin to Oklahoma City). The lower April temperatures for both Texas and southern Oklahoma evidently slowed the development of the first-generation offspring, resulting in the latest recolonization of the areas north of 40N in the Journey North first sighting records (55.7%, Table 2). Thislate arrival is in contrast to the arrivals in 2012 in which only 3% of the sightings occurred in the last observation period (Table 2). This delayed beginning to the production, together with the low numbers, were surely factors that led to the all-time low number of hectares at the overwintering sites during the 2013-2014 winter season.

2017

The mean temperature for March 2017 was 7.3F above the long-term average and the highest yet recorded. While the median arrival date (26March) was later than average (21March), arriving monarchs rapidly advanced beyond 35N such that only 28% of the first sightings were recorded for 30-35N and 56% recorded from 35-40N. The rapid advance beyond 35N resulted in two unusual events: massive clustering in northern Oklahoma beginning on 4Aprilwhich is described in detail in a Blog posting – Spring roosting: A rare event and a wind-aided surge of these monarchs northward from 7-9April that advanced the front 300miles – well into Nebraska. This event is described in another post to the Blog – Monarch Population Status (5/11/2017). In this case, monarchs were well ahead of emerging milkweeds, egg dumping was common on the few that were above ground and some eggs were subsequently frozen at the northern limits of this push.

We tracked the development from egg to adult for eggs laid 9-10April on tropical milkweeds in large containers maintained outside or our greenhouse in Lawrence, KS. The shortest time from egg to adult was 45 days – at least 15 days longer than if these same eggs had been laid in Texas rather than Kansas. It follows from these observations that distributing eggs too far north too soon contributes to competition among larvae due to egg dumping and perhaps greater predation on eggs. In addition, the loss of some eggs and larvae due to freezing temperatures and a delay in the development of the more northerly part of the distribution results in a higher mean age at first reproduction for the first-generation cohort. That in turn delays colonization of all areas north of 40N as shown by the late first sightings in 2017 (42.9%, Table 2). The overall result of the return migration and the colonization by the first generation was a modest decline in overwintering numbers from 2.91ha in 2016 to 2.48ha in 2017 (-0.43ha).

2018

The March temperatures in 2018 were also above the long-term average (+5.4F), but the outcome differed from that of both 2012 and 2017. In this case, 70% of the first sightings were in the 30-35N range. The monarchs were mostly confined to Texas and southern Oklahoma due to cooler temperatures in April from Texas north to Kansas. The result was the production of a large first generation that, on average, developed more rapidly than the first-generation cohorts in 2012 and 2017. The movement north of 40N was aided by warmer than average May temperatures (+7.0F) in the Midwest. Those elevated temperatures resulted in an earlier colonization of the northern breeding area with only 16.6% of the sightings being recorded in the last observation period (Table 2). As a consequence of these conditions, the population grew from 2.48ha to 6.05ha (+3.57ha). These conditions were similar to those that preceded the development of the population in 2006 (6.87ha).

Summary

These narratives demonstrate the complexities of the interactions of returning monarchs with the environmental conditions encountered during March and April. The development of the population is largely determined by the timing of the return together with the numbers arriving along with the weather conditions that restrict or enhance the expansion of the colonizing population. The limits of movement defined by weather conditions determine the latitudinal distribution of eggs, egg and larval mortality, the growth rate of immatures and the mean age of first reproduction for each returning cohort. In the future, elevated temperatures in March are likely to be associated with more rapid expansions of the breeding population resulting in smaller cohorts of first-generation offspring moving north. A later arrival of these monarchs in the summer breeding areas will also lead to smaller summer and fall populations and later migrations.

Acknowledgements

The interpretations in this text are largely based on Journey North’s first sightings maps and the data they are based on. The value of this data set, started in 2000, lies in the volume of first sightings reported through the winter to the 31st of July. Janis Lentz kindly organized a subset of the data for analysis.

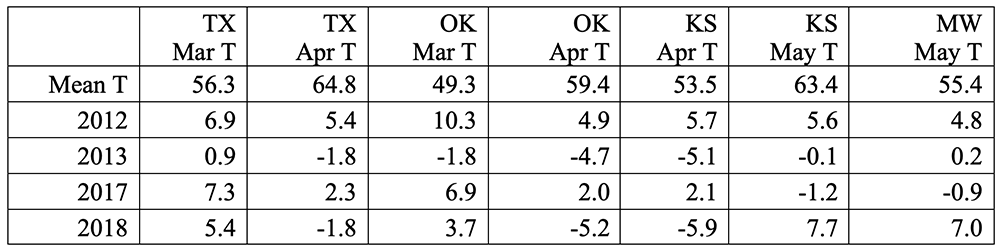

Table 1. Deviations from the long-term (1902-2000) mean temperatures for the months and states indicated.

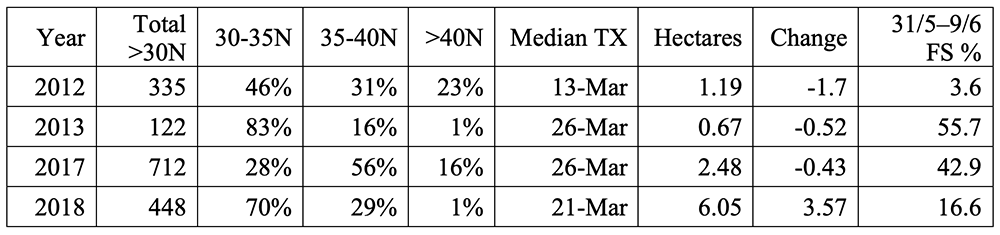

Table 2. Total first sightings from 30N to >40N latitudes from 1March to 2May with percentages sighted across the latitudes for each year. Median dates of first sightings in Texas, hectares measured at the end of the season and net change from the previous year are listed. The last column shows the percentage of first sightings recorded from 31May to 9June (see Appendix).

Appendix

The first sightings above 40N were sorted into four 10-day intervals from 1May-9June to assess the timing and number of first-generation monarchs arriving across the northern portion of the summer breeding range. Relatively few first sightings are recorded after 9June. That date is close to the end of directional flight by the first generation. The spring migration appears to stop on or close to the 12th of June as the difference in daylength from one day to the next drops below one minute. For a full discussion of this issue, see Monarch Puzzle Wrap Up.

Distribution maps of first sightings reported to and recorded by Journey North for 1January to 2May for the years indicated. The data in this analysis were based on sightings from 1March to 2May. Sightings were summarized from north of 40N from 1May to 9June as well. The line representing 40N latitude extends from the northern border of Kansas to Philadelphia.

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.