29 May 2023 | Author: Chip Taylor

Preamble

The first draft of the text that follows was written without consulting the literature. I wanted to work out my interpretations without the weight of the points of view of others. While I drew on my memory of the literature for the portions of the narrative dealing with demography, the behavioral interpretations were based on my experience. The idea was to add references later, and I have done so, but the list of relevant texts is surely incomplete. In my search of the literature, I came across a paper published in 2018 (Fisher, A., et al. Climatic Niche Model for Overwintering Monarch Butterflies in a Topographically Complex Region of California) that I should have remembered. It’s likely that prior knowledge of that paper would have changed my approach to the subject. As it stands, some of what follows validates the niche model outlined in that paper and it could be said, that the model, at least the portion that deals with overwintering, supports my interpretations. Just as there are no quantitative data to assess the validity of the model at this time, there is no way to validate my interpretation of what happened in the fall of 2020 and the 2021 growing season. Both are based on known properties of overwintering sites and conditions and known behavior of monarchs and both appear to be reasonable based on our current state of knowledge.

The Western monarch puzzle: the decline and increase in monarch numbers

by Chip Taylor

Introduction

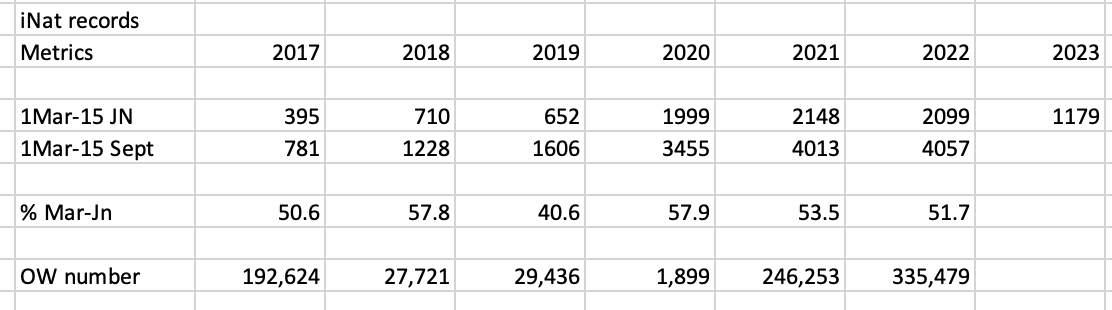

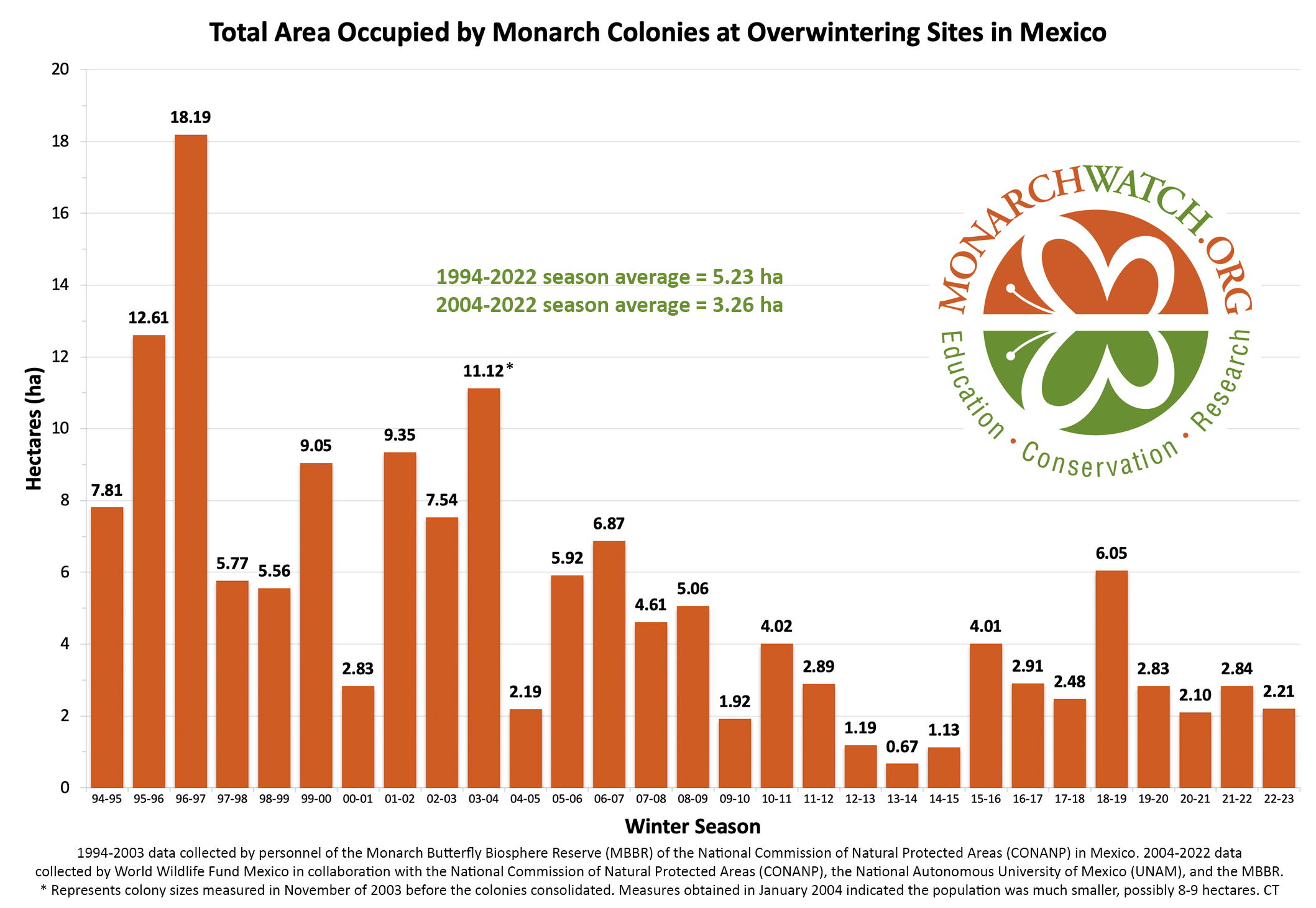

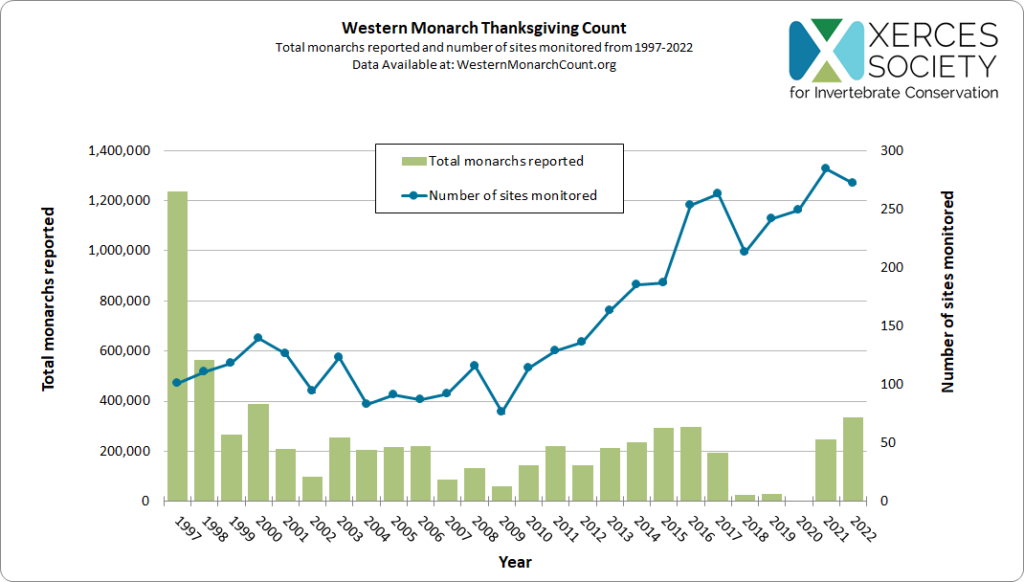

The Western monarch population declined sharply in 2017 followed by further declines in 2018 and 2019. Even more alarming, and yet perplexing, were the counts of 2020 and 2021. The Thanksgiving counts in 2020 yielded only 1849 monarchs at California overwintering sites from San Diego County in the south to Sonoma County in the north (Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count Data, 1997-2021). Of the 249 sites examined, the vast majority had zero to less than 20 monarchs, and there were only 5 sites with more than 50 (westernmonarchcount.org). These numbers were taken as a clear sign that the population was below the theoretical extinction threshold and that recovery from such a low number was problematic (Pelton, et al., 2020, Semmens, et al., 2016). Yet, the Thanksgiving count in 2021 yielded 246,253 monarchs at California sites – an over 100-fold increase – and the 8th highest count in the records since 1997 (Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count Data, 1997-2021). There have been many attempts to explain this rate of increase since it’s impossible for a cohort of 1849 overwintering monarchs to initiate a cascade of reproduction over 3-4 generations that would result in a large fall migratory population. This result is improbable since the number of surviving females would have been less than 600, and the known rates of mortality for all life stages indicate that rates of increase are strongly constrained. Clearly, the population growth in 2021 was initiated by thousands of females, perhaps 10s of thousands. The need to understand the increase leads to questions about where those females came from.

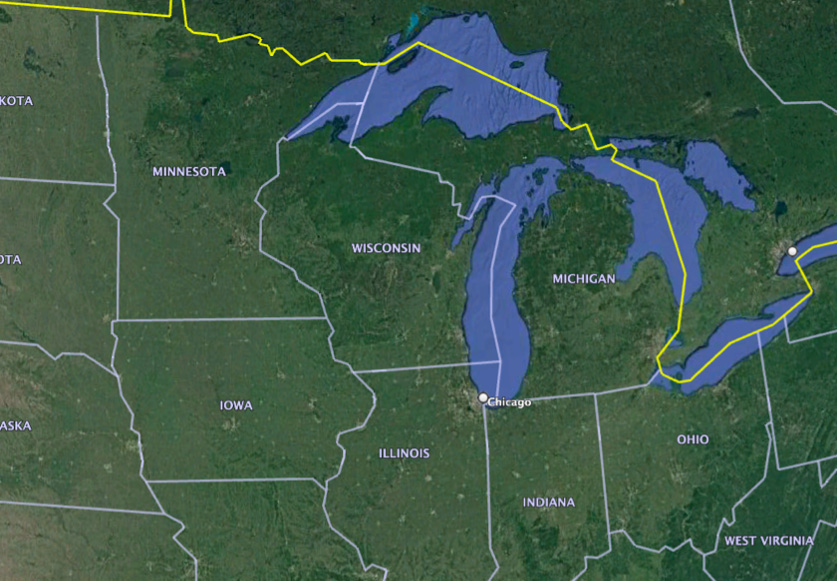

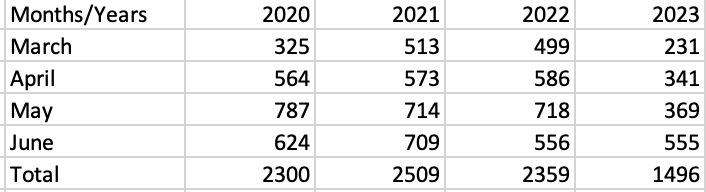

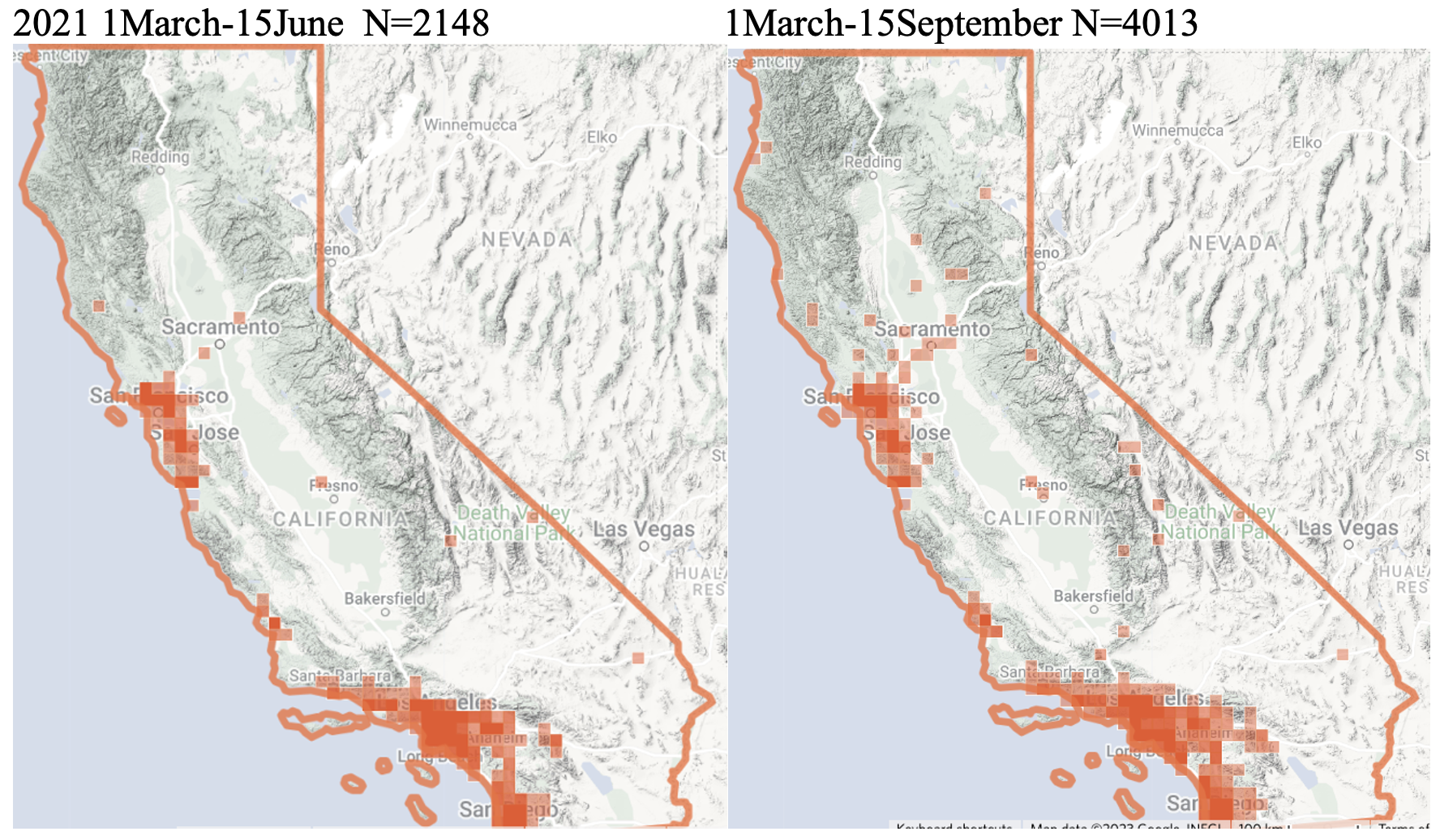

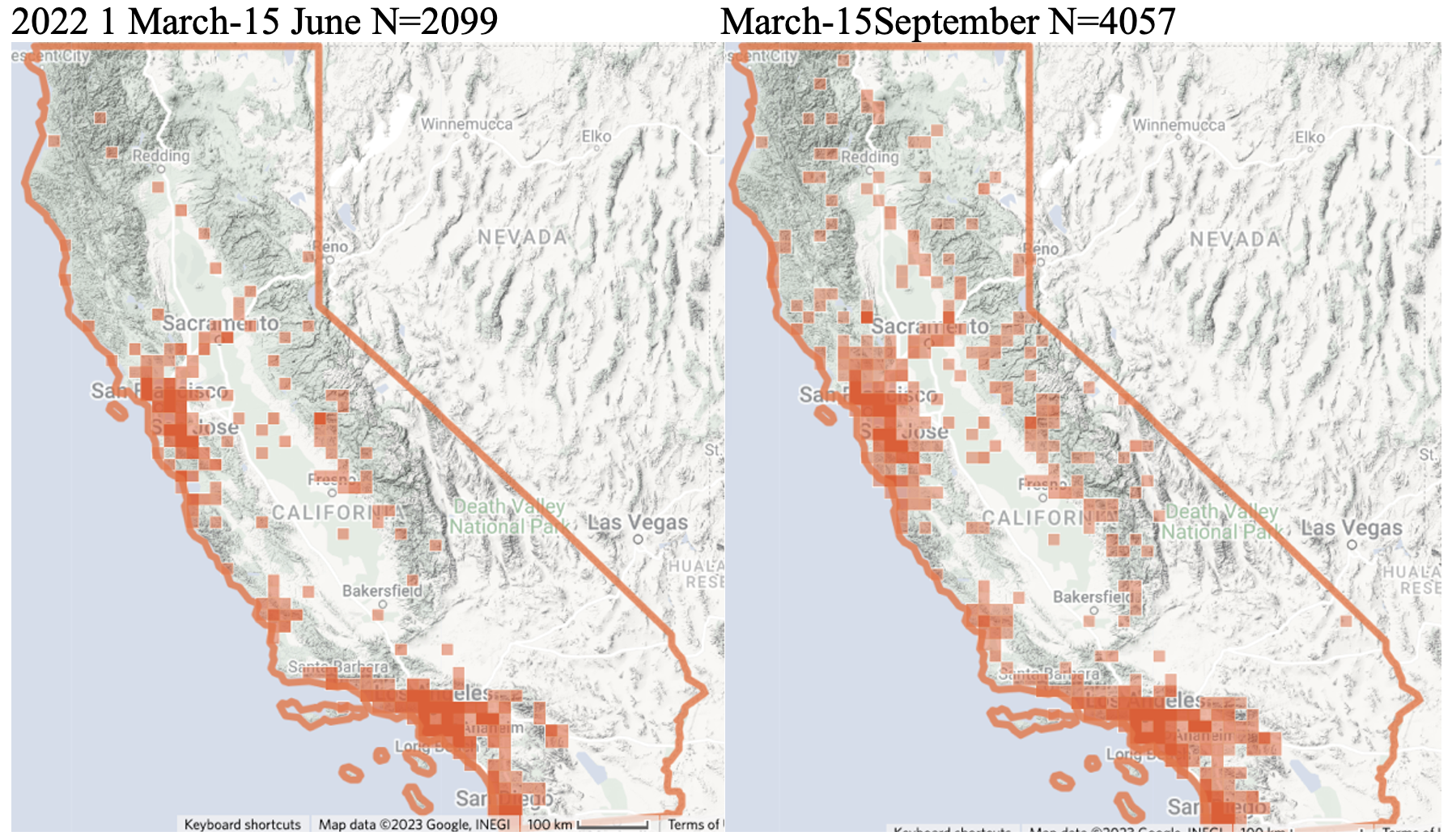

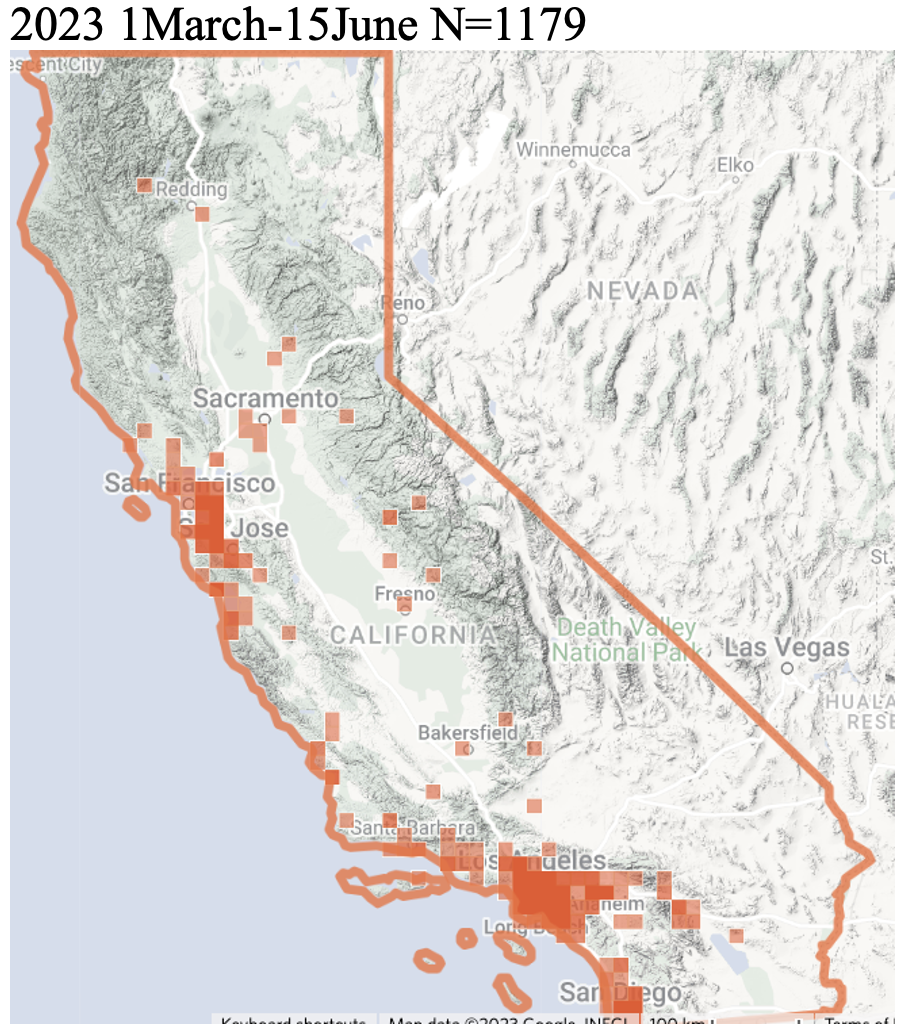

In the text below, I will make the case that, due to the all-time high temperatures along the coast in September and October in 2020, large numbers of non-reproductive monarchs overwintered inland from the coast in small scattered clusters and that these monarchs survived to mate in late February and March. The high temperatures during September-October may also have resulted in many butterflies terminating reproductive dormancy both before and after reaching coastal areas. Some likely dropped out of the migration and failed to reproduce in areas with few or no milkweeds. Others, especially in urban areas where milkweeds were available, continued breeding through the winter months (James 2021, James et al. 2021). The overwintered females, perhaps joined by some breeding monarchs from urban areas, mated and moved inland. These females laid a sufficient number of eggs to produce a large first generation that then migrated eastward to the Sierras and the inner mountain West where, in the course of 3, and in some cases, 4 generations, a migratory population of more than 300K monarchs progressed toward the California coast in September and October. Unlike in 2020, these monarchs encountered October temperatures that were slightly below or close to the long-term average all along the California coast leading to a resurgence in numbers at the overwintering sites.

This interpretation is based on the behavior of diapausing monarchs that seek moderate (60-75F) to cool (40s-60F) temperatures to maintain a non-reproductive condition through the migration and the winter months. Additional support for this hypothesis comes from the decline in monarch numbers since 1998 at overwintering sites in the three southern-most California counties. These declines appear to be related to both increases in temperature from September through December and a general decline in monarch numbers (see Addendum). The estimations of the number of reproducing females required to create a large first generation that migrated to breeding areas are based on data and estimations of mean number of eggs per female and the probabilities of surviving from one generation to the next.

Interpretation

In the narrative that follows, I will outline an explanation for why the overwintering Western monarch population appeared to be at an all-time low in 2020 yet increased in a spectacular manner in 2021. I will explain why the low numbers at overwintering sites in 2020 and the relatively high numbers in 2021 are rooted in the monarchs’ response to temperature that is based on their need to remain non-reproductive during the winter months. In effect, I will set forth a hypothesis based on the response of adult monarchs to temperature. Support for the hypothesis is based on observations of monarch behavior in Kansas, Texas and Mexico and the decline in the numbers of sites and monarchs as temperatures increased over the last decades in San Diego, Orange and Los Angeles counties.

The scenario I envision was foretold by Fisher, et al., 2018 in their niche model paper that predicts the tendency for wintering monarchs to move away from the coast to winter in cooler locations in the coastal foothills if coastal temperatures continued to increase. As they pointed out, “Our results suggest that estimating the size of the western overwintering population in the future will be problematic, unless annual counts compensate for a shift in the distribution and a potential change in the number and location of occupied sites.”

Let’s start with what we think we know about the influence of extremely high temperatures on monarch migrations and on monarch physiology and behavior. Three things are likely to happen when the temperatures are extremely high (>90F) during the migration. First, the start of a migration can be delayed. Late recolonizations in May and June can result in later migrations that can be further delayed due to high temperatures that stop the migration or reduce the number of flight hours per day (Taylor, et al., 2019). Second, some of the monarchs will become reproductive since high temperatures increase the production of juvenile hormone and ovariole development. Third, monarchs become highly dispersed and do not form high density clusters under high temperatures. The latter point is supported by observations of clustering behavior when temperatures are in the 90s in Kansas and Texas and the numerous observations of temporary clustering sites that form from mid-October into early November in many areas along the California coast. Next, we need to know how monarchs respond to temperatures while at overwintering sites. Surviving from late October to reproduce in late winter or early spring requires that monarchs remain non-reproductive – a state of low endocrine production, low metabolism and low energy expenditure. To stay non-reproductive, monarchs appear to seek low temperatures that help maintain this condition.

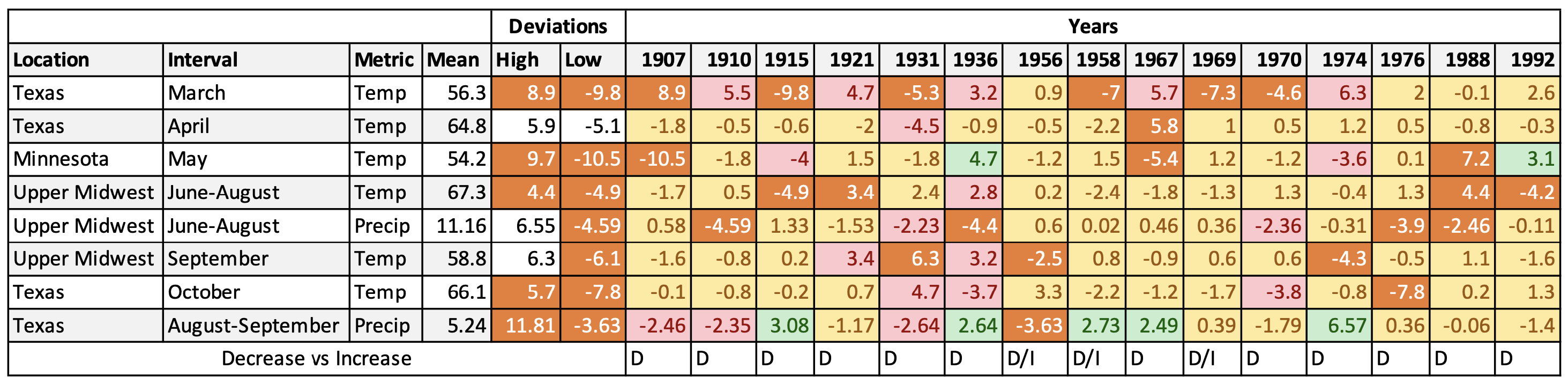

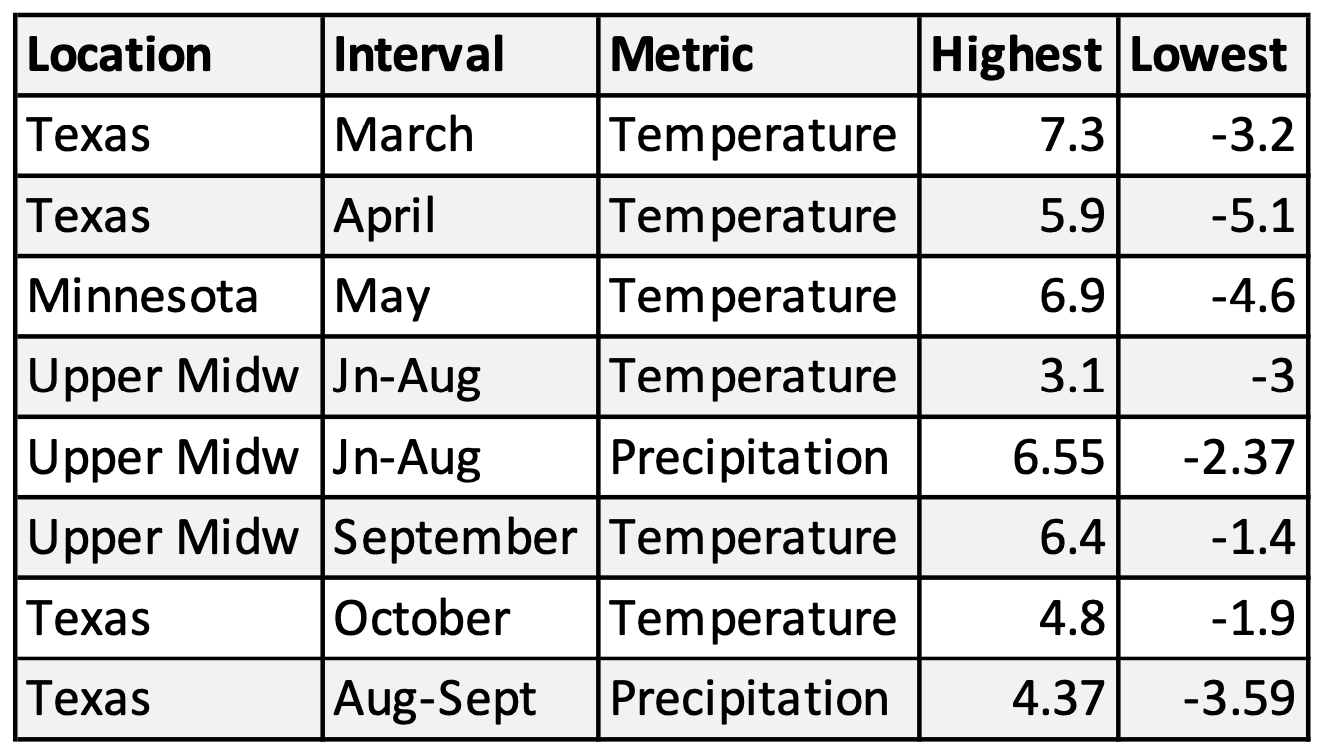

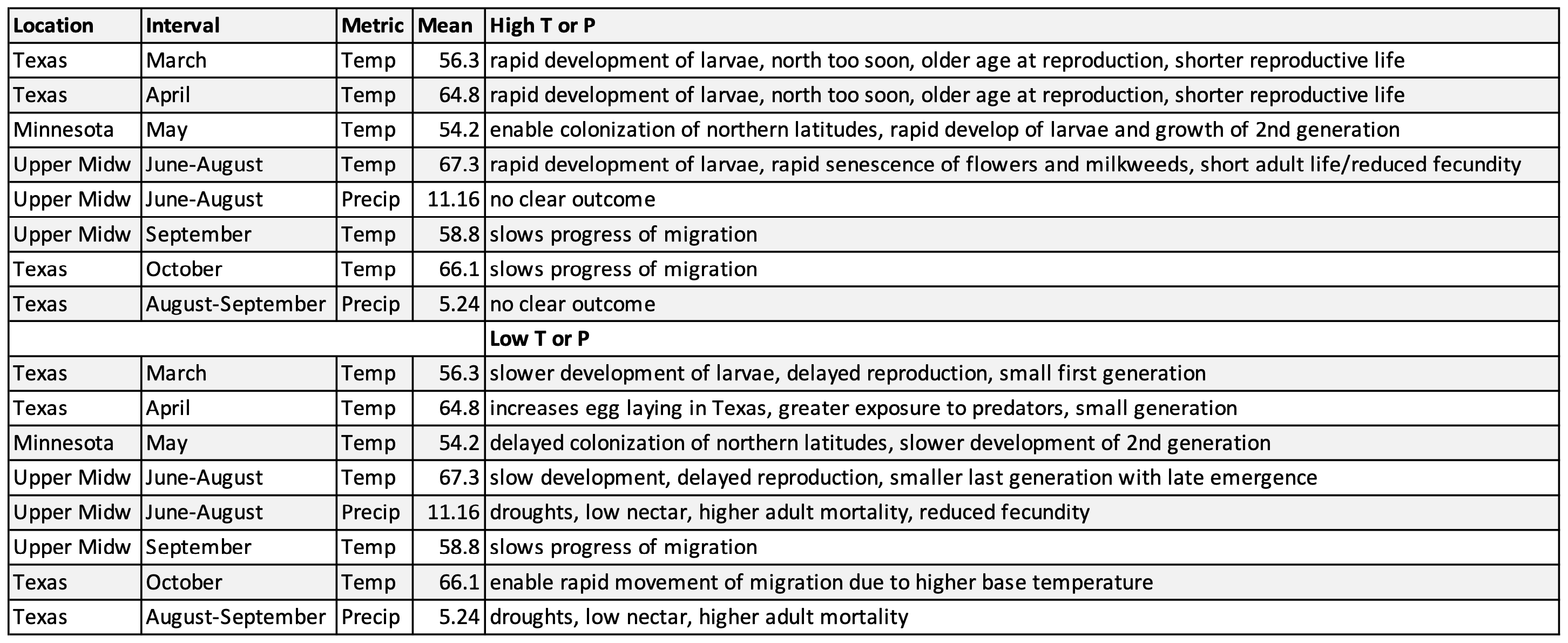

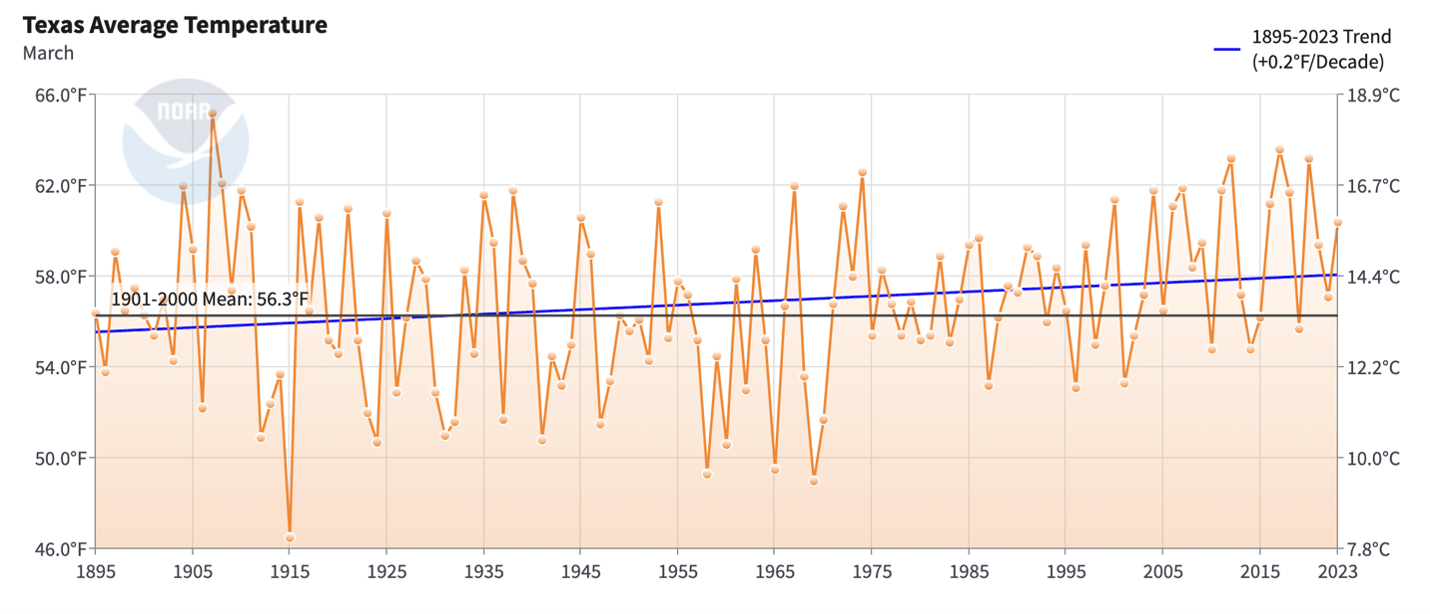

Based on these considerations and data on the conditions that favor population growth, I have been trying to develop a stage specific model for the Western monarch population. The premise of the model is that an analysis of the effects of both physical and biotic factors within a stage allows us to predict the numbers entering the next stage. By tracking the results through all stages, it should be possible to a predict the relative size of an overwintering population. There are five stages in the West: overwintering, reproduction by overwintered adults, migration by first generation monarchs to the inner mountain West and Northwest, summer reproduction and fall migration. The temporal sequence of those stages is reasonably clear and is similar to the same stages in the East. What is less clear is where the monarchs breed in the summer months that return to the coastal areas each fall. Sometimes, the main production areas seem to be in the NW, and in other years (such as 2021) the conditions in the inner mountain west to the east of California seem to be the more favorable for monarch production. As part of the model, I’ve developed a large matrix of the monthly and stage specific time periods for the years 1998-2021. The matrix includes the temperatures and rainfall amounts for each interval. The idea was to use these data to determine if the physical factors could account for the decreases and increases in monarch numbers. The one and only monarch data base in the mix was the yearly monarch counts – the Thanksgiving counts coordinated by the Xerces Society. The underlying assumption has been that these totals (or the totals each year from the 20 sites measured most consistently) are reasonable representations of the population and therefore serve as a measure of the size of the monarch population. Indeed, comparing stage specific temperatures, and sometimes rainfall, seemed to work, and there is a reasonable but not entirely satisfactory explanation for the crash in the population from 2016-2019 based on these values. Yet, there were inconsistencies. There were years in which the Thanksgiving counts were lower (2001) and others when they were higher (2014) than expected based on the temperatures and rainfall amounts from one stage to the next. Overall, the explanatory power of the assembled data, once promising, was rather weak. Something was missing.

I was stuck but still hopeful. There was a mismatch between the metrics and the overwintering numbers. I was either using the wrong metrics or the numbers weren’t adequately representing the size of the population and both could be off. The metrics were certainly off being too course to reveal the details of population growth. But what about the Thanksgiving counts?

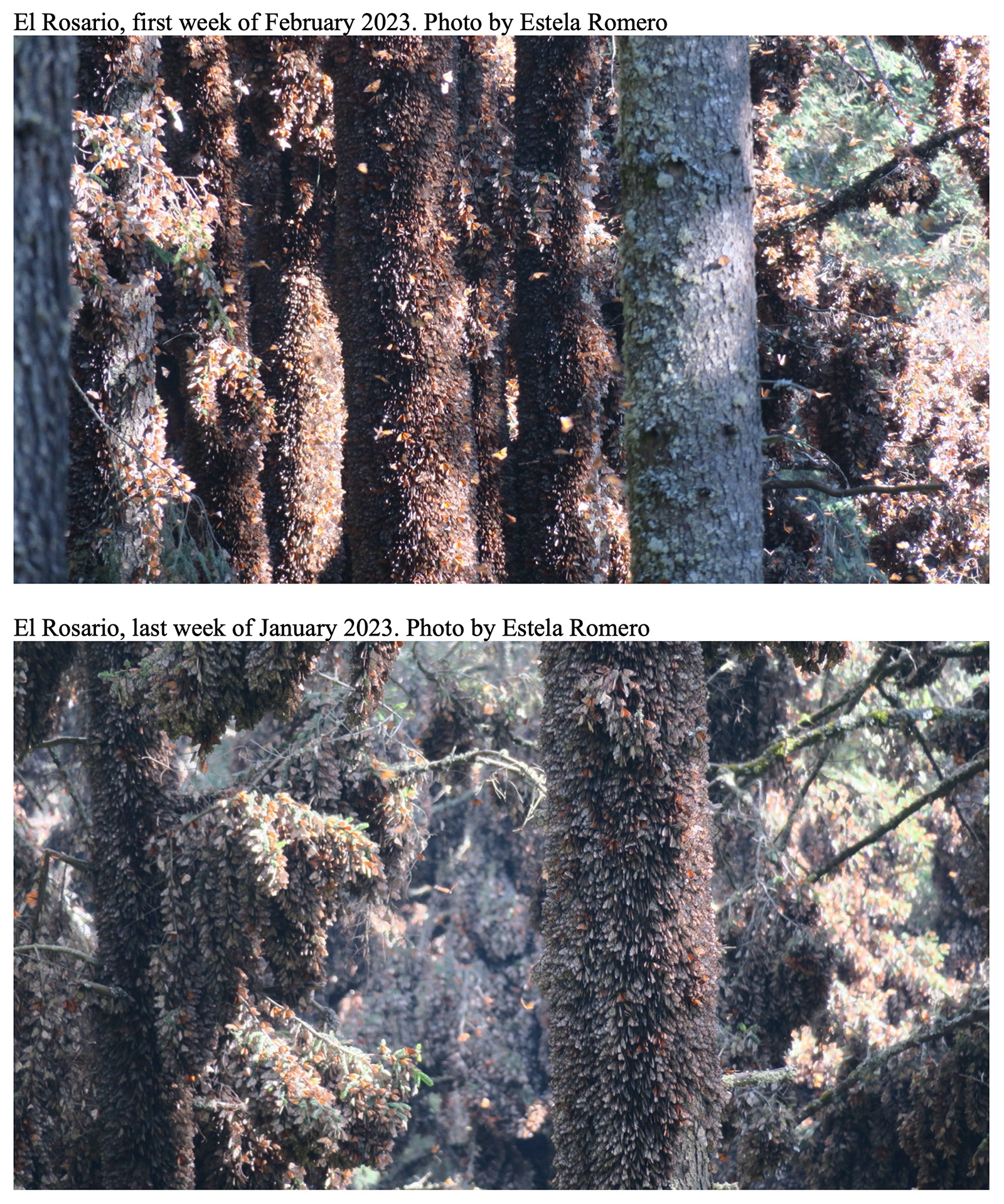

One approach to getting unstuck is to write down all your assumptions and to detail all you know about each assumption. In the case of the Thanksgiving counts, there are several assumptions. First, all the teams making the counts are equally skilled at “estimating” the number of monarchs in each cluster they examine. Second, all, or nearly all, roosting sites are located each year and that all clusters at each site have been identified and counted. Third, all, or nearly all, the migratory monarchs cluster at the coastal sites. Indeed, Schultz et al., 2017, assume that the monitoring constituted “an independent index of the total abundance in that year.” Human error is expected since making the counts is extremely difficult, demanding and tiring. Kudos to all those who have engaged in these counts and doing their best to be accurate. Given the conditions, the number of sites, the coordination required and more, these counts are a significant achievement. So, as counts go, due to the difficulties, we can expect some over-counts and under-counts at various sites. It follows that another assumption might be that these counting errors cancel each other out with the result that the counts are reasonable estimates of monarch numbers at the end of each season. Ok, if we accept that premise, we can ignore the third assumption – that all the monarchs cluster at the overwintering sites. The numbers don’t lie, except when they don’t represent what we think they do. It’s reasonable to expect that the counts are accurate measures of the population. After all, the monarchs in Mexico represent all areas east of the divide, with the exception of peninsular Florida, and are consolidated into a small number of colonies each year. So, why shouldn’t that be true in the West? In Mexico, the colonies occur on massifs at 10,500’ or higher where the temperatures for most of the winter range from the 30s at night to the 60s during the day with the temperature rarely reaching the low 70s at the sites themselves. In effect, these are low temperature islands that are surrounded by areas with much higher temperatures at the lower elevations. Thus, in the winter months, to stay non-reproductive, the monarchs need to remain on these islands. Freezing conditions are more likely to be a threat to monarchs in Mexico than high temperatures. That said, warmer winters are expected in Mexico in the future.

Monarch behavior during the winter months along the California Coast is different. Rather than staying in one place, monarchs are on the move when temperatures allow movement. Initially, monarchs reaching the coastal areas settle in small to modest numbers in a large number of scattered sites as well as the well-known wintering sites. Most of these temporary sites are abandoned with the occupants moving to more permanent sites as the temperatures continue to cool in late October and November. The presumption here is that monarchs leaving temporary sites seek clustering locations that are both cooler and better protected from variable weather conditions. These movements generally end by late November. The clusters/colonies are thought to be at their seasonal maximum at that time hence the timing of the Thanksgiving counts. However, the numbers generally begin to dwindle following (but perhaps even before) the Thanksgiving counts such that counts in the following January indicate numbers that are lower by roughly 35 to 45 %. Further, a large proportion of the sites that had monarchs during the first count no longer have monarchs during the second count. In addition, there are locations where the numbers increase from Thanksgiving to January and sites where the declines over that 5-6week interval are quite low. The reasons for the declines are not clear. Mortality could be one factor, and it could be that monarchs are still moving in an attempt to stay in reproductive diapause by seeking cooler and more protected sites. The assumption by Schultz et al., that counts are a useful index of abundance is difficult to justify. Due to the continuous movement of monarchs in the early fall and whenever the temperatures allow through the winter season, the numbers appear to be a moving target. While there is no doubt these counts are of value, the fact that a hundred and fifty more sites are counted now than as recently as 2011 makes it difficult to assess current and historical trends and to associate those numbers with changing physical and biological conditions.

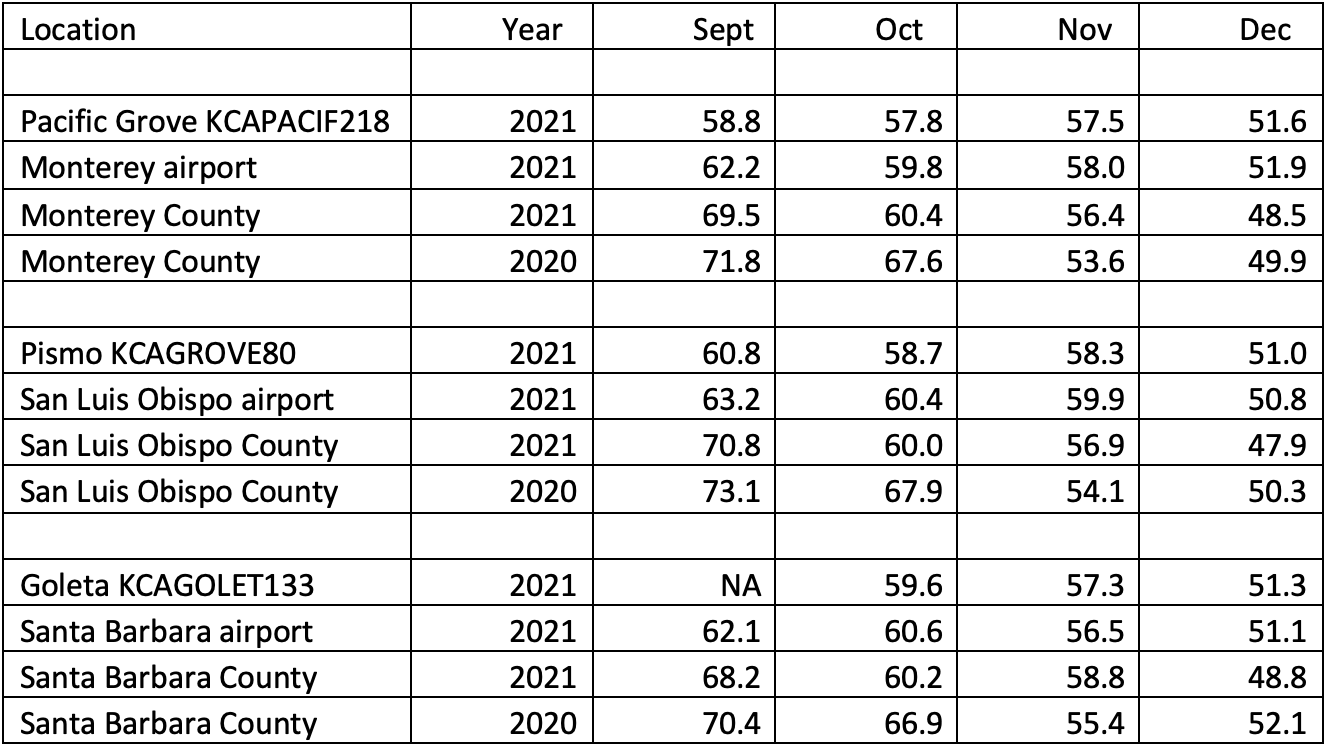

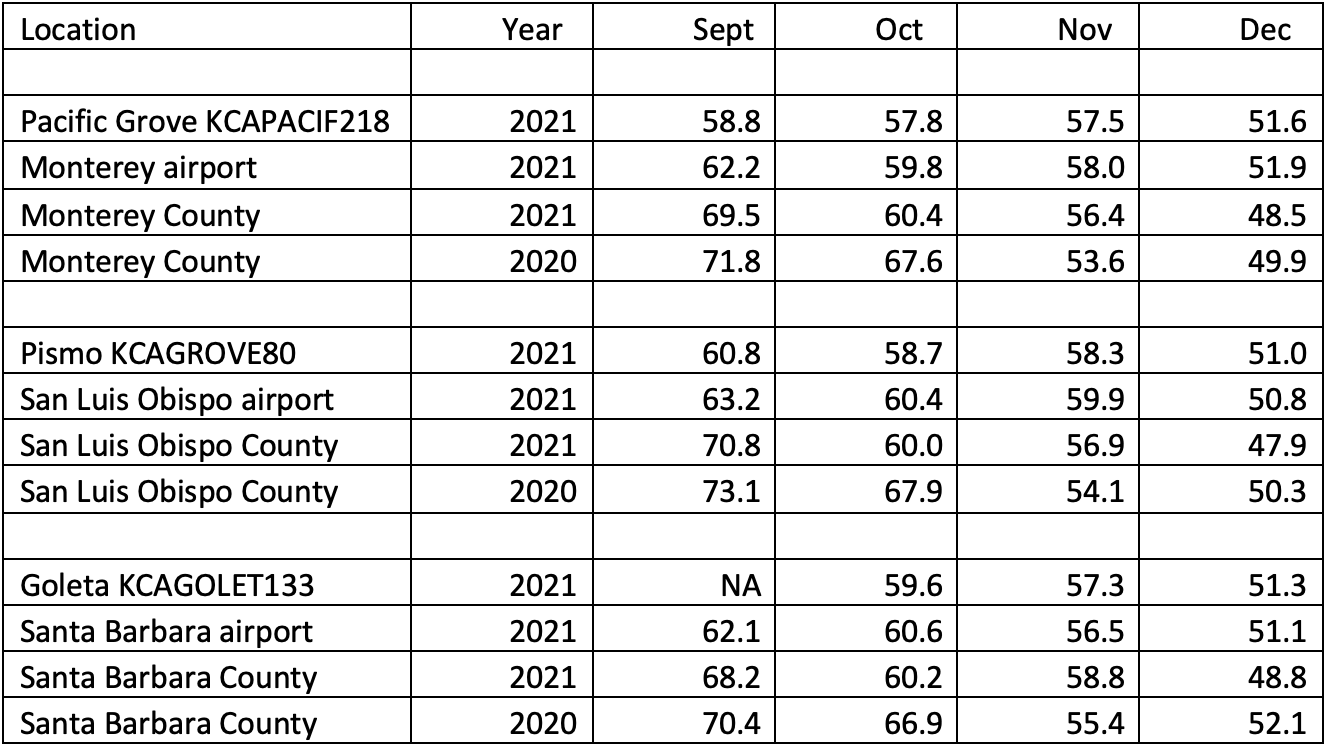

While temperatures along the coast have historically been cooler than the interior as the monarchs arrive in mid-October, as the season progresses, and the interior cools, it can actually become cooler in many locations away from the coasts (Table 1). That the temperatures along the coast have been increasing during the winter months and that monarchs have been leaving the coastal sites earlier over the last 20 years or more seems clear (Addendum, Figure 1). Monarchs which used to stay clustered at some sites until early March are now leaving sites in large numbers in late January and early February according to many accounts although actual data on this point are scarce. Unfortunately, we don’t know the fate of monarchs that leave overwintering sites. There seem to be three options – they die, they become reproductive, mate and search for milkweeds that are scarce to non-existent at that time, or they move inland to sites which are cooler and more suitable for maintaining a non-reproductive condition. It’s probable that all three happened with the latter being the most frequent outcome for monarchs seeking cooler temperatures. I’m assuming that some of these monarchs survive from January through mid-March singly or in small scattered clusters well inland from the coast, perhaps at 1500-3000ft.

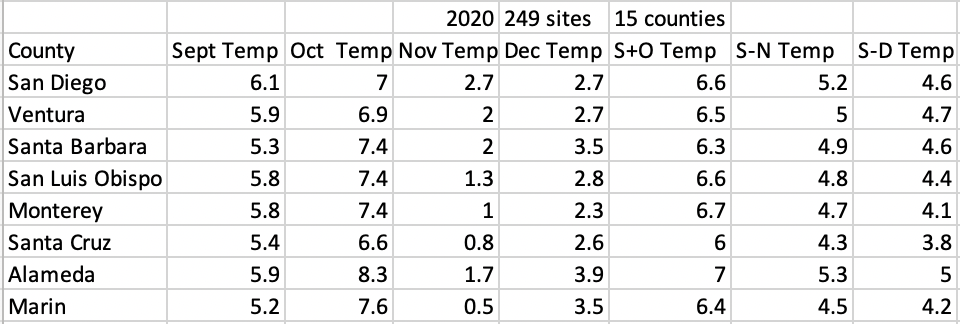

Table 1. Mean temperatures for months indicated for Tempest weather stations close to overwintering sites, nearest airports and counties for 2021 and county temperatures for 2020. The latter show the extreme temperatures for September and October in 2020. Temperatures are generally lower near overwintering sites for September and October but are warmer than county means during November and December (except for November Santa Barbara). Overwintering site temperatures are closest to airport temperatures in December. Counties generally represent large areas inland from the coast with lower temperatures than coastal areas from late fall through February.

Monarchs seek moderate temperatures. They need to stay non-reproductive for months. So, what happens if the coastal areas are too warm in mid-October? What if there are no temperature gradients, they are too weak or it is uniformly hot? It’s clear that there is an optimal temperature range for staying non-reproductive, and though we don’t know exactly what those limits are, monarch behavior appears to be telling us that they are seeking temperatures below 70F when migrating and need temperatures in the high 50s to 70s to reach and settle in to the overwintering sites to stay in those sites through the winter requires temperatures in the 40s to low 50s. There is a well understood relationship between temperature and the density of clusters that form during migrations and colony establishment. This relationship is key to what happens in California, and particularly what happened in 2020. First, two observations from Kansas are relevant. If the temperatures are in the 90s during the migration in eastern Kansas, most of the monarchs stop migrating and seek the shade and higher humidity found in the gallery forests along the rivers, streams and drainage areas. Once in these shaded and more humid sites, the monarchs roost in the trees often singly, but frequently in small and open, even scattered, clusters of 6 or so. Monarchs will stay in these locations for days if the temperatures remain in the 90s. The second observation involves clustering at the end of the day. When temperatures are in the low 80s, monarchs form clusters scattered loosely in trees from ground level to much higher. If the temperatures are in the 60s, with overnight lows in the 30s expected, the clusters are higher and denser in the trees with few or none of the monarchs settling near ground level. Similarly, in Mexico, the first clusters are loose and scattered and slowly consolidate as the temperatures become cooler. In effect, the colonies become smaller and smaller as the winter progresses usually reaching the maximum density and smallest area occupied by mid-December. That’s when the colonies are measured by WWFMX in collaboration with CONANP, UNAM and the MBBR. These observations indicate that cluster formation and density is a function of behavioral responses to temperature with loose or no clusters forming when it is hot to tight, cohesive clusters forming when temperatures are at the lowest that allow for flight.

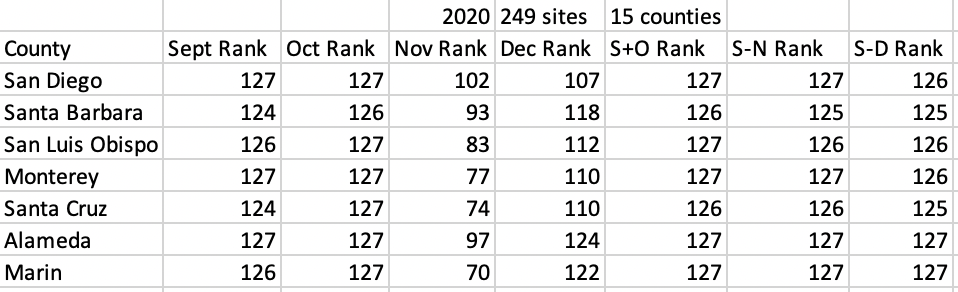

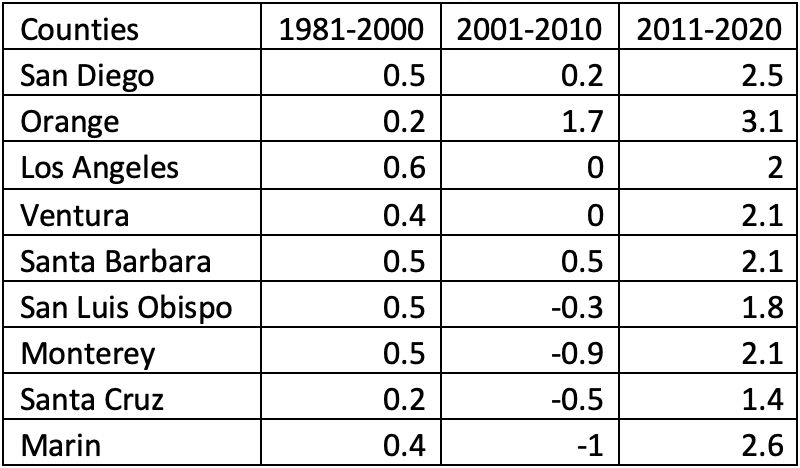

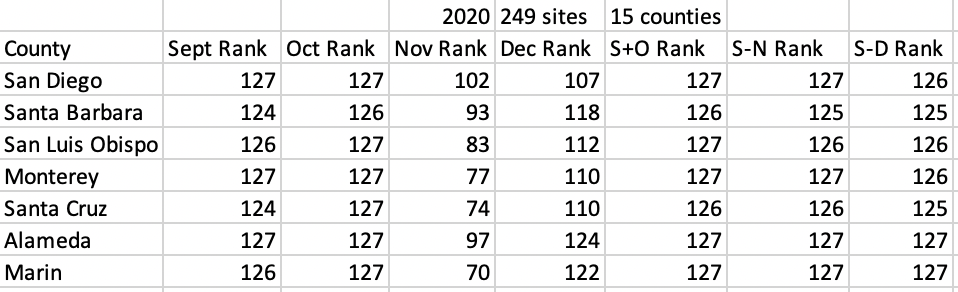

These behaviors bring me to what happened in 2020 along the California coast. The temperature records for all the counties along the coast go back to 1895. That’s 127 years, and those years are ranked from coolest to hottest. I first looked at the mean temperatures for October for counties from San Diego to Marin. All averaged over 7F above the long-term means (7.0-7.6) and all but one (SB ranked 126) were ranked as the hottest in the record to date. The rankings were similar, but the deviations were lower when using 30yr means (5F-6.1F). I then looked at the mean temperature for September, a period during which the monarchs are moving toward the coasts. The results were the same, and when I combined September and October and then, September, October and November and finally added in December, each showed that those means ranked 125-127 (Tables 2a, 2b).

Table 2a. Temperature rankings for September through December separately and combined for 2020. There are 127 years in the record ranked from coldest to hottest with 127s being the hottest mean monthly temperatures in the record.

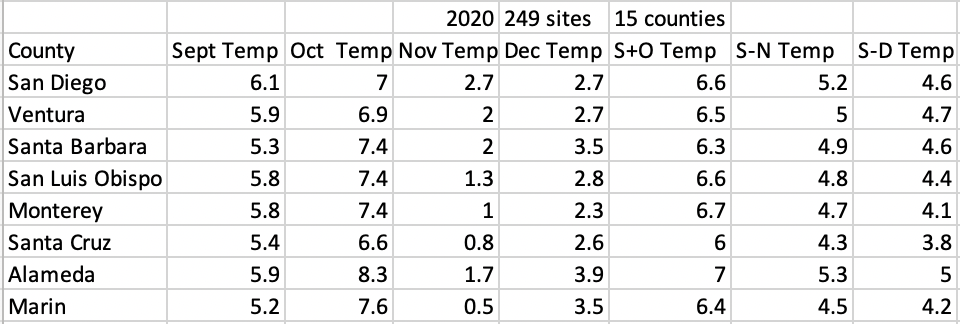

Table 2b. Deviations from long-term mean temperatures for the intervals indicated.

Given these extremes and the known effects high temperatures have on the initiation and progress of migrations, as well as the physiological and behavioral responses of monarchs to these conditions, what happened in 2020 that rolled over to the influx of monarchs in 2021? Here is the scenario that seems likely. The migration in 2020 started late and moved slowly due to the temperatures in the 90s along inland pathways leading to the coastal locations. For example, the mean maximum temperatures were the third highest in the 126year record for Fresno and the highest in the 75year record for Sacramento. Some monarchs became reproductive on the way to the coast, these monarchs dropped out of the migration altogether (James 2021, James et al. 2021). Other monarchs seeking cool temperatures stayed individually or in small clusters in the foothills and drainages inland from the coast and due to the continuing high temperatures stayed in these areas rather than moving to the coast. Some of the monarchs reaching the coast became reproductive and continued to reproduce through the winter where milkweeds were available. Others, a mere 1849, clustered at an all-time low number of sites along the coast. Santa Cruz, the county with the largest proportion (38.55%) of all the wintering monarchs in 2020, also had a high retention rate (91.2%) for the sites that were counted during the Thanksgiving and January surveys. The mean temperatures at Santa Cruz were the lowest among all counties in October, November, October-November and for September through December (Table 2). This result is consistent with the interpretation that monarchs seek the coolest locations or some combination of temperatures, protection from direct sun and strong winds.

The resurgence in the numbers at the overwintering sites in 2021 suggests that spring reproduction was extremely successful, so successful, that it seems likely that the resurgence was founded by a large number of mated females that began laying eggs in late February, a process that continued into April. Given the behavior I described with respect to clustering and the need for monarchs to seek out temperatures that enable them to stay non-reproductive, it seems likely that many of the overwintered females that began the breeding in 2021 overwintered singly or in small clusters at sites interior of the usual overwintering sites. Monarchs originating from winter breeding populations in urban areas may have also moved inland in the spring adding to the reproduction that produced a new generation from late April through May (James 2021, James et al. 2021).

Monarch demography

Part of the challenge in explaining what happened during the 2021 breeding season is not only figuring out the origins of females that started the first generation, but estimating how many survived to reproduce. That reproduction had to result in a large first generation that subsequently colonized the summer breeding areas, mostly east of California, followed by additional reproductive success that yielded an initial migratory population of at least 300,000 monarchs.

For the purpose of illustrating the potential reproduction of a cohort of females, I’ve assumed constant rates of mortality from one generation to the next. However, the incidence of parasitism by tachinid flies and infection by the protozoan Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (O.e.) tends to increase as the season progresses. Such increases would reduce both the proportion of larvae reaching the pupal stage and those surviving to the adult stage. In the case of the surviving adults with O. e., their fitness to reproduce would be compromised. We also need to recognize that realized fecundity, i.e., the mean eggs per female per generation, varies with temperature, nectar availability, and the distribution, abundance and quality of milkweeds. These factors also affect population growth. In other words, the calculations below represent a best-case scenario that is most often approached early in the season.

Calculations

The calculations that follow are based on estimates taken from the literature (Grant et al., 2020, Nail, et al., 2015, De Anda and Oberhauser, 2015, Oberhauser, et al., 2017). I used constant rates of egg laying and mortality for a cohort of 10,000 females for three generations. The results look promising but are not realistic.

10,000 females x 250 eggs = 2,500,000 eggs x 0.03 proportion surviving to pupal stage =75,000 x 0.76 = 57,000 new adults x 0.85 proportion that reproduces = 48,450 x 0.45 proportion of females = 21,803. These calculations therefore yield a 2.18 rate of increase in females per generation. If we multiply 21,803 x 2.18 for three generations, we get 225,884 females or a total potential migratory population of about 510,000. That’s more than enough monarchs to yield an overwintering count of 246K. However, it is unlikely that these rates of increase would be the same from one generation to another. They could be lower due to an increase in O.e. and tachinid parasitism or the losses due to other predators, all of which tend to increase as the season progresses. That could decrease the proportion surviving the pupal stage and the number of new adults substantially. As an alternative, we might imagine conditions that would allow females to lay more than 250 eggs followed by higher survival through the larvae stages that would lead to an increase in the population. The later scenario seems less realistic to me. It should be noted that the proportion of eggs (0.03) surviving to the pupal stage used in these calculations is probably too high by a factor of 2. If true, and all other estimates were the same as above, it would take about 20,000 females to produce a migratory population of 246K wintering monarchs. That number would have to be even greater if the incidence of O.e. and tachinid parasitism increased thus reducing the size of the reproductive population. The point of making these calculations is to show that to produce an overwintering population of 246K required an initial female population numbering in the 10s of thousands, probably 30,000 or more. While a portion of these females may have originated from scattered areas of winter reproduction, the majority were probably overwintered monarchs that survived in small, highly dispersed clusters in the coastal foothills (Fisher et al., 2018) that went undetected during the surveys for overwintering monarchs.

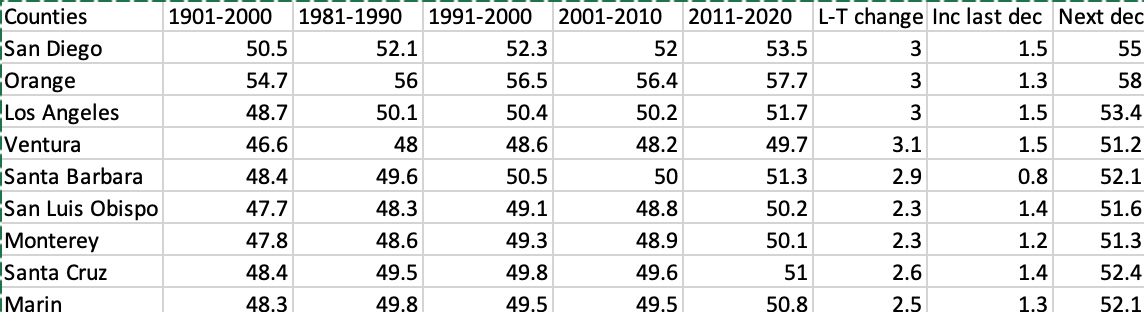

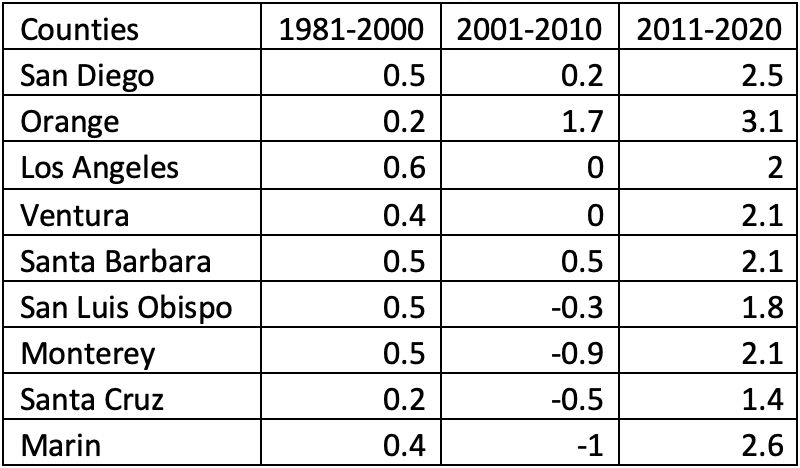

If these interpretations are correct, it is likely that the Thanksgiving counts may underestimate the size of the overwintering population during years when the October – November temperatures are substantially above the long-term average. The increases in temperature along the coast during both the fall and winter suggest that southern counties in California are likely to see fewer and fewer monarchs in the coming decade. In addition, the tendency of monarchs to seek cooler locations will lead to an increasing dependency on the more northerly overwintering sites. However, if the rapid increases in temperatures during October and November along the California coast (Table 2) continue at a rate similar to that of the last decade, monarch overwintering along the coast (Table 3) is likely to decline. Should this be the case, it will become increasingly important to maintain and improve on the structural features of the overwintering sites that offer the best protection throughout the winter.

Table 3. Increases in mean temperatures for October-November for the intervals indicated. Note the exceptional rate of change in the last decade for all coastal counties.

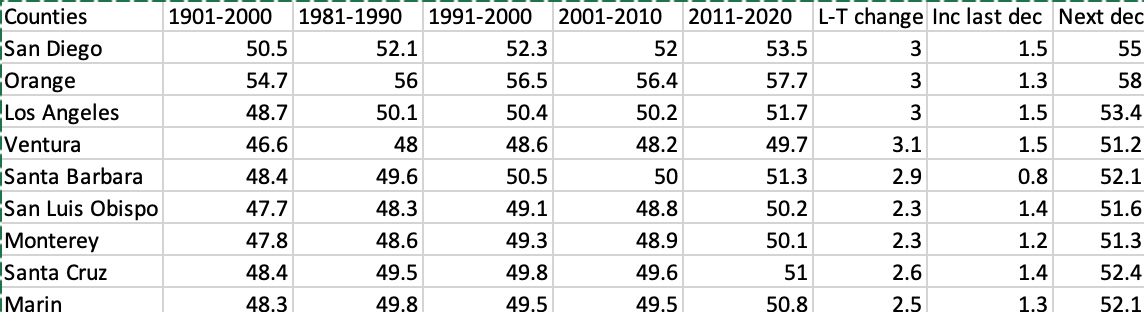

Table 4. Mean December through February temperatures for coastal counties in California.

The first column represents the long-term mean followed by means for the last four decades.

The long-term change, the increase from the previous decade and the projected increase are shown in the following columns. Most of the increase in mean temperatures occurred in the last decade. Monarch numbers at overwintering sites trend lower as mean December-February temperatures increase beyond 51.0F in San Diego, Orange and Los Angeles counties (Addendum Figure 1). The estimations for the next decade were based on the increases during the previous decade. Given the recent trends, the means for the next decade could be higher than shown.

Analysis

The analysis I’ve used to support the interpretations outlined in the text is based on monthly means for counties. While the counties are all coastal, their areas vary with some extending significantly inland, with the result that there is some loss of equivalency. Further, the means can only be seen as proxies for the conditions at the colony sites and should not be taken as exact representations of the temperatures which are likely to be lower at specific overwintering sites (Table 1). Means can also conceal events such as short intervals with weather extremes that can have a significant impact on the monarch population. For example, after an exposure to a 3-4day interval with temperatures in the mid 70s or higher, many overwintering monarchs are likely to break diapause. The same is likely to occur during the migration. Mean temperatures also don’t capture mortality due to other weather events such as high winds or extreme rainfall. All the same, there are patterns associated with increasing temperatures that appear to explain much of what has been happening at overwintering sites along the coast from 1997 (when the counts began) to the present. Mean temperatures have risen from 1.8F to 1.0F per decade from San Diego to San Francisco. The range of mean maximum temperatures is even greater being from 2.7F to 1.3F per decade. While these changing conditions affect the overwintering monarchs, and likely their movement and survival, a deeper dive into the weather data is needed to understand what determines the number of monarchs that arrive at the overwintering sites each winter.

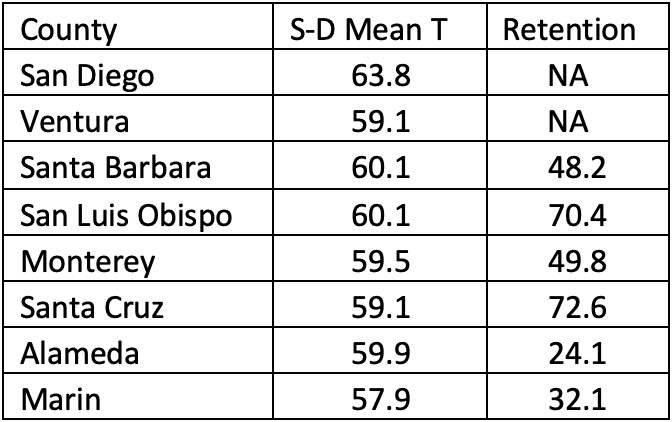

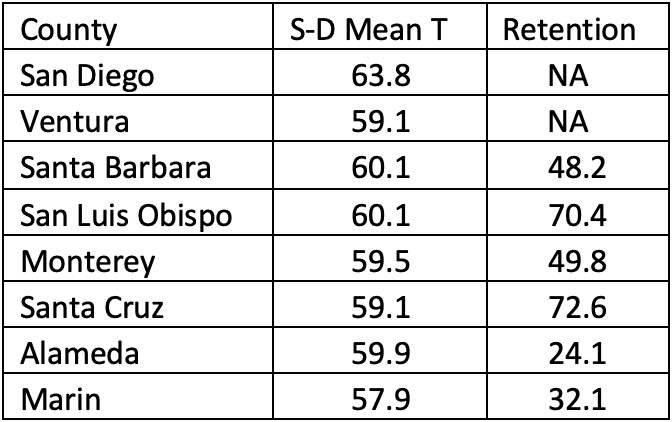

Retention

In addition to the Thanksgiving Counts, counts are made for most counties again in January. Retention refers to percentage of monarchs remaining in each county once the January counts are completed. These data are summarized by county, for the 5 years (2017-2021) during which both Thanksgiving and January counts are available in Table 4. The numbers of monarchs in both San Diego and Ventura counties were too low for meaningful estimates of retention. Two factors, temperature and site quality, probably account for much of the retention. But high winds and other weather events could account for some of the decline. The overall retention doesn’t appear to be associated with differences in temperature among years for colonies collectively, e.g., warmest year (2020) and the coolest year (2021) have similar rates of retention (63.8 vs 62.8). However, within years in the 4 core colonies (SB, SLO, MT, SC), the highest retentions are often associated with the counties with the lowest temperatures, such as Santa Cruz in 2020, Table 6. The retention rates for both Alameda and Marin counties are both low, but there are no indications those rates are associated with temperatures.

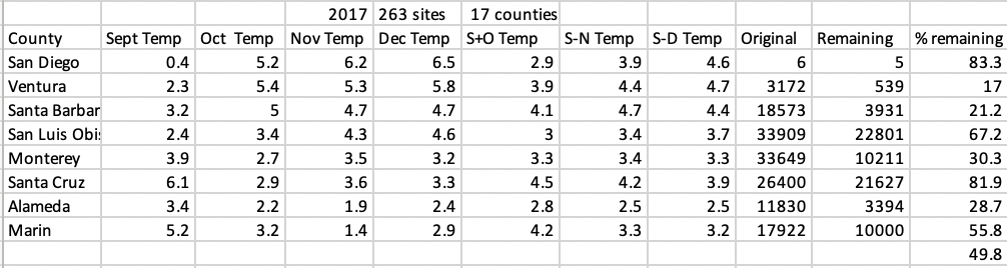

Table 5. Mean temperatures for September – December and percentages of monarchs remaining at all overwintering sites in each county at the time of the January counts for the years 2017-2021.

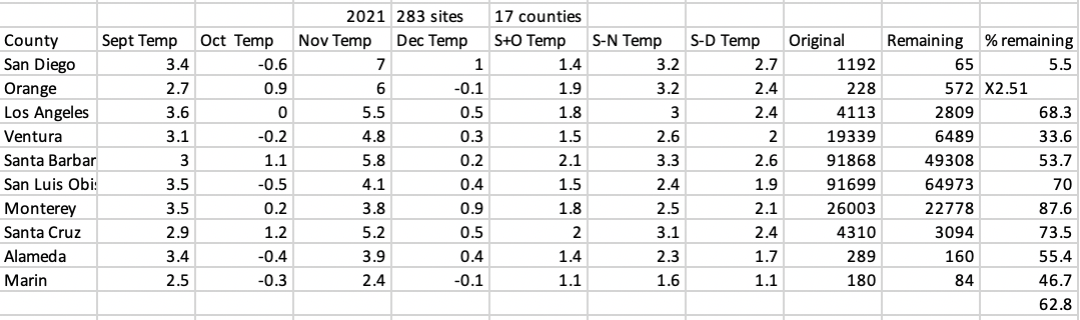

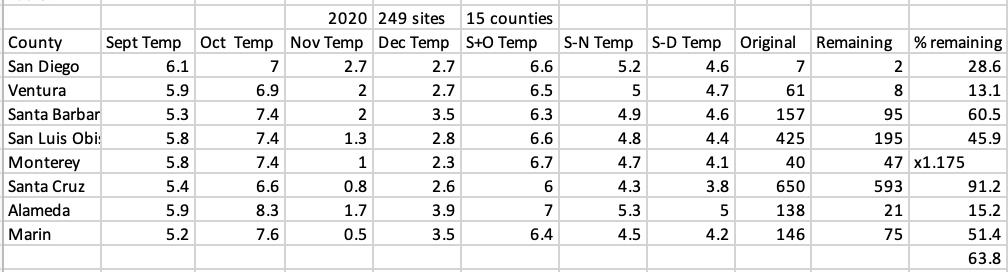

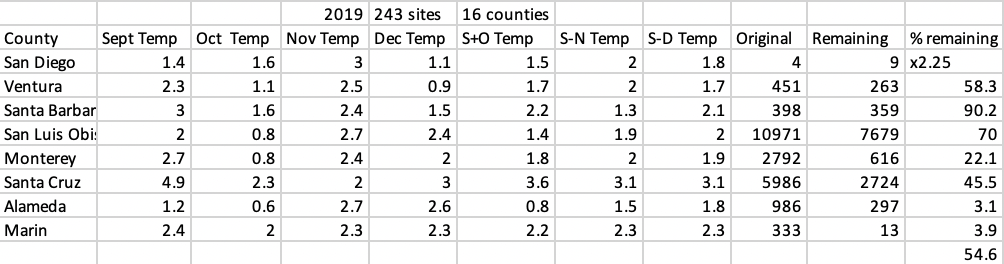

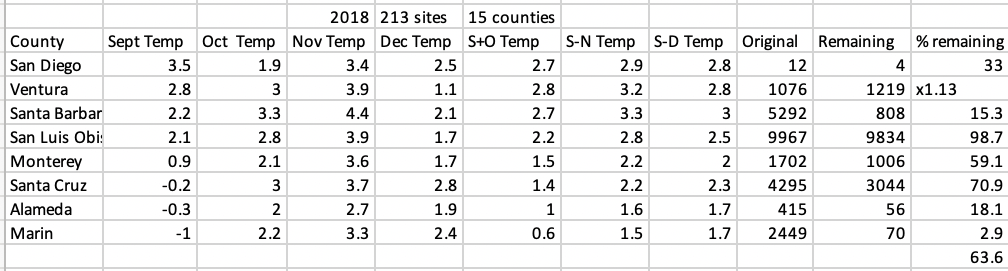

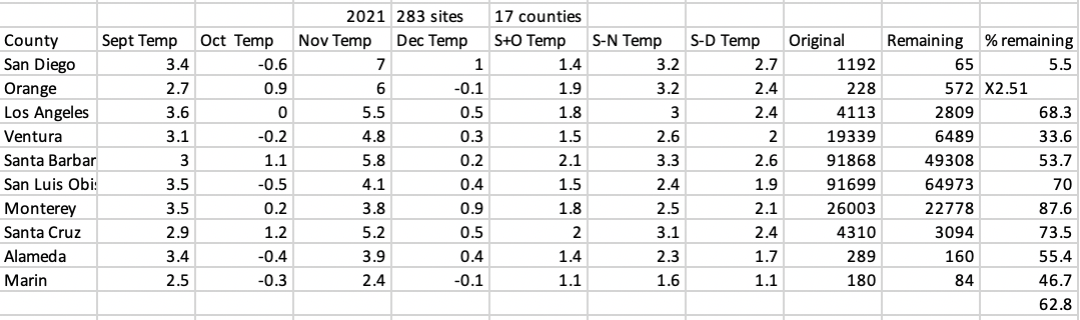

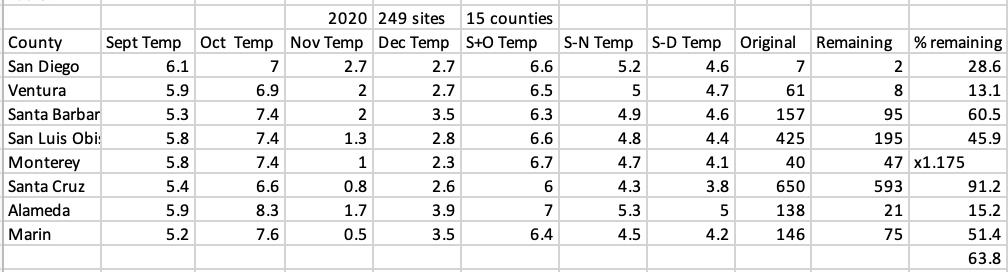

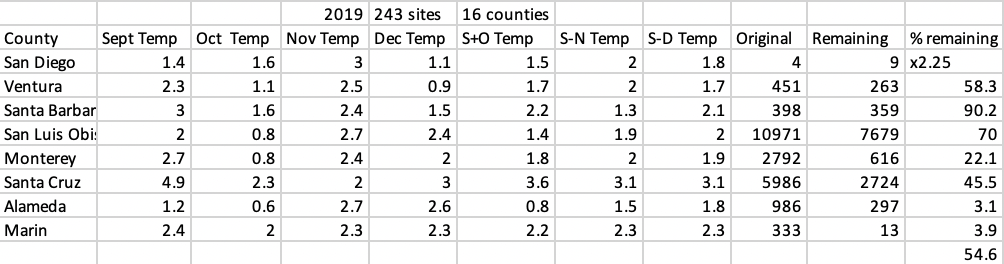

The temperature records for 8 counties are summarized for the years 2017-2021 in Tables 6-10. The data represents deviations from the long-term means for each county. September represents the interval during which most of the long-distance migration occurs. October and November temperatures correspond to the period of arriving at and settling in at overwintering sites. December represents a period of decline in number of occupied sites and numbers per site. These tables also include the original and January counts.

Extremely high temperatures in September, as in 2020, Tables 1 and 6, probably reduced the numbers of monarchs reaching coastal sites by causing some to break diapause and drop out of the migration. Attrition due to the lack of nectar resources under these conditions could also be a factor. Unfortunately, there are no means to assess the impact of September temperatures on the number of migrants reaching the coast. October and November temperatures are key. They can be too extreme as in 2020 or favorable by being close to the long term means as in 2021, Tables 6 and 5. December temperatures were included to determine if they influenced the declines within and among years. While there is no clear association of these temperatures with the declines, more analysis might be helpful.

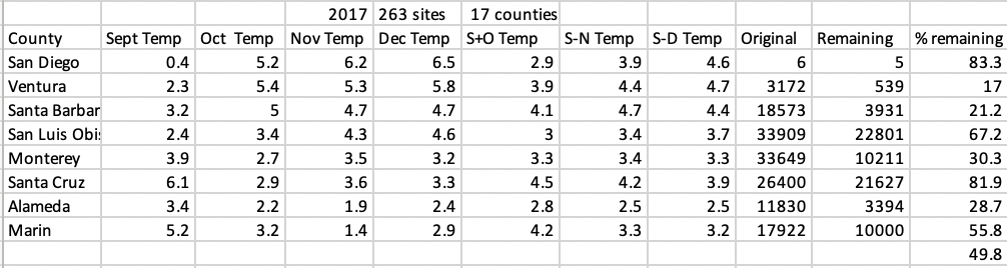

Table 6. Deviations from the long-term mean temperatures for 10 counties surveyed for monarchs in 2021. Original refers to the number of monarchs in the Thanksgiving count and remaining refers to the numbers counted at the same sites in the following January.

Table 7. Deviations from the long-term mean temperatures for 8 counties surveyed for monarchs in 2020. Original refers to the number of monarchs in the Thanksgiving count and remaining refers to the numbers counted at the same sites in the following January.

Table 8. Deviations from the long-term mean temperatures for 8 counties surveyed for monarchs in 2019. Original refers to the number of monarchs in the Thanksgiving count and remaining refers to the numbers counted at the same sites in the following January.

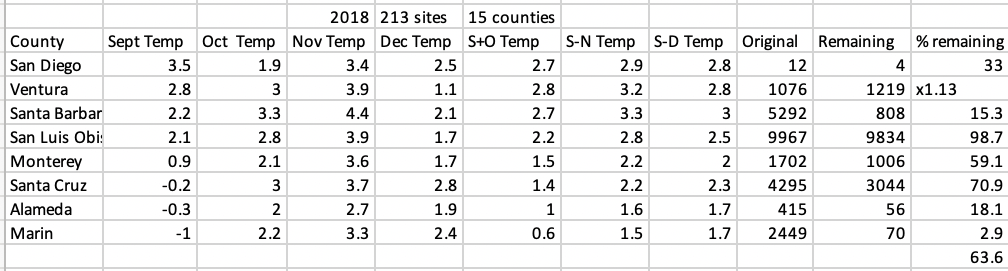

Table 9. Deviations from the long-term mean temperatures for 8 counties surveyed for monarchs in 2018. Original refers to the number of monarchs in the Thanksgiving count and remaining refers to the numbers counted at the same sites in the following January.

Table 10. Deviations from the long-term mean temperatures for 8 counties surveyed for monarchs in 2017. Original refers to the number of monarchs in the Thanksgiving count and remaining refers to the numbers counted at the same sites in the following January.

Summary

Monarchs are an enzyme. That’s the title I used for three posts to the Monarch Watch Blog to introduce the concept that monarchs operate most effectively at a limited range of temperatures for each activity. We can imagine an enzyme activation curve for each behavior. These optimal ranges have not been defined analytically or experimentally, but we know enough to approximate their limits. For example, temperatures ranging from 65-75F favor migration. Migratory flight appears to diminish either side of this range. Overwintering monarchs appear to do best when temperatures range from 30-60F with monthly means in the high 40s. Both of these conditions apply to the fall and overwintering conditions along the California coast where it is getting too warm both during the fall migration (September flights and October-November clustering at overwintering sites) and the wintering interval from December-February. These changing conditions have resulted in a decline in the numbers of monarchs overwintering in Southern California counties. The tendency for diapausing monarchs to seek temperatures within the range that maintains a non-reproductive condition leads to the progressive abandonment of warmer and less protected sites during the period of cluster formation and throughout the winter months. The result is both consolidation at some overwintering sites and the movement away from many sites as early as December. In the case of 2020, when few clusters formed, it is likely that the fall population overwintered inland in small scattered clusters as suggested by the niche model of Fisher, et al., 2018. Breeding populations that carried over from summer breeding in urban areas may have been augmented by fall monarchs that became reproductive. Offspring from these populations may have moved inland (James et al. 2021) along with overwintered monarchs to produce a large first generation. The numbers of females (10s of thousands) appeared to have been sufficient to produce a first generation that colonized summer breeding areas, mostly in the inner mountain west from May to mid-June in 2021. The multi-generation reproduction that followed produced a migratory population of 300,000, or more, monarchs that populated the overwintering sites under the near average temperatures that occurred from September through November 2021. The rates at which temperatures are increasing during the fall and winter along the California coast suggest that overwintering numbers are likely to decline in the coming decade. While the climate projections in Fisher, et al., 2018, were well into the future, the predicted outcomes seem to be partially represented by the distribution and abundance of wintering monarchs in 2020.

Acknowledgments

Exchanges with Paul Cherubini about Western monarchs on the WesternMonarchs@groups.io discussion list reminded me of the basics of how monarchs respond to temperatures during the migration and when clustering at overwintering sites. Jay Diffendorfer, Peter Ipsen, David James and Patrick Guerra offered their perspective on a number of points and Janis Lentz read the text and kindly pointed out missing commas, run on sentences and some non-sentences. Any errors or misinterpretations are mine.

References

De Anda, A., and K. S. Oberhauser. 2015. Invertebrate natural enemies and stage-specific mortality rates of monarch eggs and larvae. Pages 60– 70 in K. S. Oberhauser, K. R. Nail, and S. Altizer, editors. Monarchs in a changing world: Biology and conservation of an iconic butterfly. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York, USA.

Fisher, A.; Saniee, K.; Van der Heide, C.; Griffiths, J.; Meade, D.; Villablanca, F. Climatic Niche Model for Overwintering Monarch Butterflies in a Topographically Complex Region of California. Insects 2018, 9, 167. doi.org/10.3390/insects9040167

Grant, T. J., D. T. T. Flockhart, T. R. Blader, R. L. Hellmich, G. M. Pitman, S. Tyner, D. R. Norris, and S. P. Bradbury. 2020. Estimating arthropod survival probability from field counts: a case study with monarch butterflies. Ecosphere 11(4):e03082. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3082

James, D. G.; Schaefer, M.C.; Krimmer Easton, K.; Carl, A. First Population Study on Winter Breeding Monarch Butterflies, Danaus plexippus (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) in the Urban South Bay of San Francisco, California. Insects 2021, 12, 946. doi.org/10.3390/insects12100946

James, D.G.; Schaefer, M.C.; Krimmer Easton, K.; Carl, A. Reply to Davis, A.K. Monarchs Reared in Winter in California Are Not Large Enough to Be Migrants. Comment on “James et al. First Population Study on Winter Breeding Monarch Butterflies, Danaus plexippus (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) in the Urban South Bay of San Francisco, California. Insects 2021, 12, 946”. Insects2022,13,64. doi.org/10.3390/insects13010064

Nail, K. R., C. Stenoien, and K. S. Oberhauser. 2015. Immature monarch survival: effects of site characteristics, density, and time. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 108: 680– 690.

Oberhauser, K., R. Wiederholt, J. E. Diffendorfer, D. Semmens, L. Ries, W. E. Thogmartin, L. Lopez-Hoffman, and B. Semmens. 2017. A trans-national monarch butterfly population model and implications for regional conservation priorities. Ecological Entomology 42: 51– 60.

Pelton EM, Schultz CB, Jepsen SJ, Black SH and Crone EE (2019) Western Monarch Population Plummets: Status, Probable Causes, and Recommended Conservation Actions. Front. Ecol. Evol. 7:258. doi: doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2019.00258

Semmens, B. X., D. J. Semmens, W. E. Thogmartin, R. Wiederholt, L. López-Hoffman, J. E. Diffendorfer, J. M. Pleasants, K. S. Oberhauser, and O. R. Taylor. 2016. Quasi-extinction risk and population targets for the Eastern, migratory population of monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus). Scientific Reports 6: 23265.

Schultz, C.B.; Brown, L.M.; Pelton, E.; Crone, E.E. Citizen science monitoring demonstrates dramatic declines of monarch butterflies in western North America. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 214, 343–346.

Taylor, O. R., Lovett, J. P., Gibo, D. L., Weiser, E. L., Thogmartin, W. E., Semmens, D. J., et al. (2019). Is the timing, pace and success of the monarch migration associated with sun angle? Front. Ecol. Evol. 7:442. doi: doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2019.00442

Data Citations

NOAA National Centers for Environmental information, Climate at a Glance: National Time Series, published June 2022, retrieved during June 2022 from ncdc.noaa.gov/cag/

Xerces Society Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count. 2022. Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count Data, 1997-2021. Available at westernmonarchcount.org

Addendum

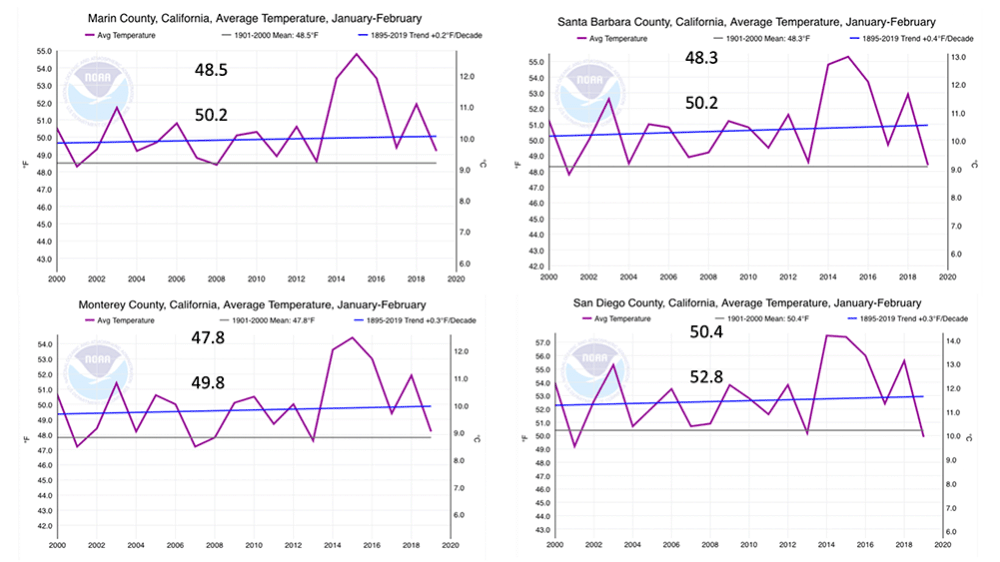

Figure 1 below and supporting commentary can be found at:

monarchwatch.org/blog/2020/02/25/monarchs-and-climate-in-the-west

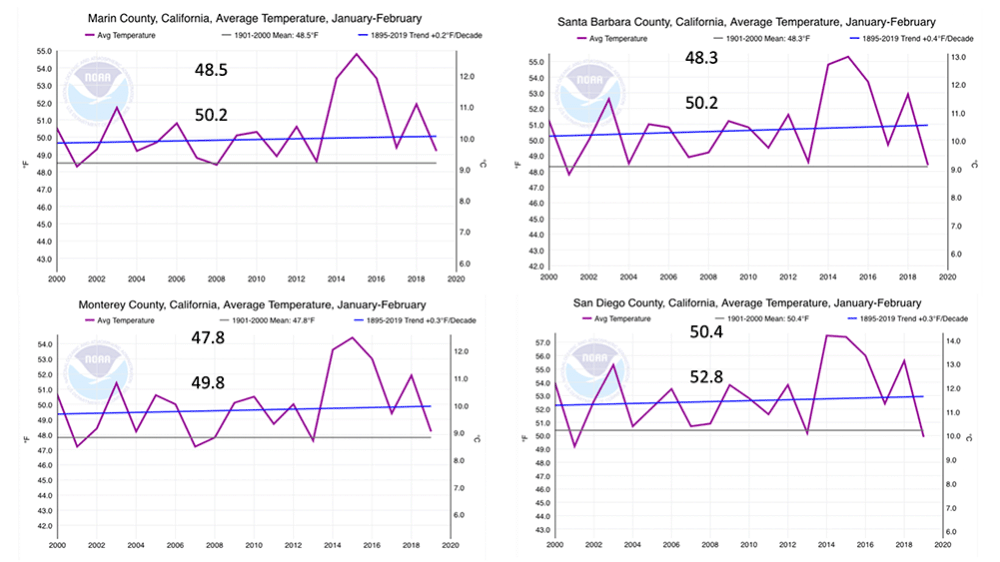

Figure 1. Both the long-term mean (upper) and the mean for the last 20 years (lower) for January–February for 4 counties from Marin in the north to San Diego in the south are displayed above. The differences between the long-and-short term temperatures range from +1.7F for Marin County to +2.4F degrees (.85–1.2F degrees/decade) for San Diego County. Along with these increases in temperature, the number of sites and individuals per site has been decreasing in the southernmost counties and while increasing in Marin County. Over the 20-year interval in San Diego, the number of sites declined from 18 to 3 while the count declined from 2,590 to 12. Overall, the data suggest that the numbers of sites and monarchs both decline as temperatures increase. Further, the data suggest monarchs are seeking cooler temperatures by moving northward along the coast. The alternative possibility is that they could be moving to cooler inland sites – if such exist.

Note 1. Although the number of females that survived the winter of 2020-2021 to reproduce is unknown, it’s possible that the number was as high as 30,000. If so, then, how many monarchs started the overwintering cycle in the fall of 2020? Generally, since females are usually about 45% of the population, the total surviving would have been approximately 66,500. If this number represented only 50% of initial population due to mortality, the starting number would have been roughly 133,000. While these numbers are speculative, they provide a glimpse of the possible magnitude of the population that overwintered in 2020-2021. It appears to have been much larger number than the1849 represented by the Thanksgiving counts.

Note 2. In theory, monarchs could return from Mexico to repopulate the West and perhaps a few do so. The entry to the West could involve monarchs entering as they followed the Rio Grande north through Las Cruces and then moved to the West into eastern AZ and western NM.

An alternative route would involve advancing through the mountains in Mexico with entry into AZ east of Nogales into southeastern AZ south of Sierra Vista. From there monarchs could advance northward into east-central AZ. Both routes are >300 miles longer than the routes that take monarchs to reach Texas. That would involve a minimum of 6 more days of flight to reach the border.

At present, there is no evidence monarchs use either of these routes to reach the US. To establish that such movements occur, we need evidence from isotopes and first sightings. To obtain the isotope evidence, worn monarchs suspected of having returned from Mexico need to be collected and analyzed. First sightings recorded by Journey North and photos from iNaturalist from March and April in the West could help as well.

Monarchs return from Mexico to TX in early March. Arrival continues until mid-April. Similar arrival times would be expected in AZ and NM. In 2020, the year of interest, there was one first sighting in Carlsbad, NM on the 20th of March along with a note that 5 others were seen nearby. There were no other reports of monarchs in NM until the first and second of May. One was described as old and tattered and another as fresh. All were sighted east of the divide. No monarchs were sighted west of the divide until 12 of May in Utah. There were no records on iNaturalist as well. So, there is no evidence from first sightings in 2020 that helps us understand the growth of the population that summer.

Overall, while it is possible that monarchs reach the US along these routes now and then, the probability that the numbers that return are sufficient to lead to substantial increases in western monarch numbers seems low.

Note 3. Ecological release is another possible explanation for the resurgence of the population in 2021. This term is used to explain explosive population growth following an event that eliminates factors that normally limit population growth. Such an explosion of butterflies occurred after the 7month drought in Texas in 2011. That drought was followed by 7months of above normal moisture starting in the fall of 2011. Evidently, due to the suppression of predators and parasites during the drought, 16 species of butterflies were able to produce large numbers which led them to expand their distribution northward into Kansas and beyond in April and early May of 2012. While precipitation in 2020 was the second lowest for the 127year record for the West Climatic Region, the more normal, but still below average, pattern of precipitation in 2021 has not been associated with explosive increases in the numbers of other butterfly species.

Filed under General | Comments Off on The Western monarch puzzle: the decline and increase in monarch numbers