Species Status Assessment and the three r’s

Friday, October 13th, 2023 at 4:42 pm by Chip TaylorFiled under General | Comments Off on Species Status Assessment and the three r’s

When species are being considered for listing under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) by the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), a Species Status Assessment (SSA) is usually prepared. This assessment is based on the available science, and in some cases, the opinions of scientists that work closely with that species. At the core of the assessment are the three r’s: resilience, redundancy and representation. Resilience refers to data that may or may not support the ability of the species to respond to stochastic (random) events. Redundancy represents an assessment of the ability of a species to respond to catastrophic mortality. Representation seems to have two interpretations, the ability of a species to adapt to long term changes in the environment and/or the species role in the ecological processes in the range it occupies.

Resilience and redundancy are somewhat similar in that both assessments address evidence of the ability of a species to respond to external factors such as weather events, diseases, or the actions of predators or competing species. Representation seems to be more difficult to assess since it depends on a known history of adaptability which is often lacking. Similarly, evidence of the role a species plays in the ecological processes of the environment in which it resides is also difficult to assess. Representation would seem to rely quite often on subjective assessments rather than quantitative data. For example, what is the role/contribution (value) of an herbivorous insect that is one of many species that feeds on a particular plant, but whose main contribution is as a food item for foliage-gleaning wasps and birds? How is that judged? As a practical matter, it is quite difficult to assess how the presence of a species fits into the ecological mix in a particular environment. Still, it’s possible to define species that are host specific as lacking in adaptability if their host is removed from the environment by disease or other factors. Weevil and moth species, and perhaps many other insects, were lost as the result of the blight that killed the American chestnut (Anderson, 2017). This is an example of co-extinction. Co-extinction is likely to apply to most of the 300 species of insects that use ash trees as their hosts. Many will become extinct due to their inability to adapt to other hosts as their host ash trees (18 species) are eliminated by the introduced Emerald Ash Borer (Horne, et al., 2023). These will be silent extinctions. There will be no SSAs or clamor of any kind to save these species.

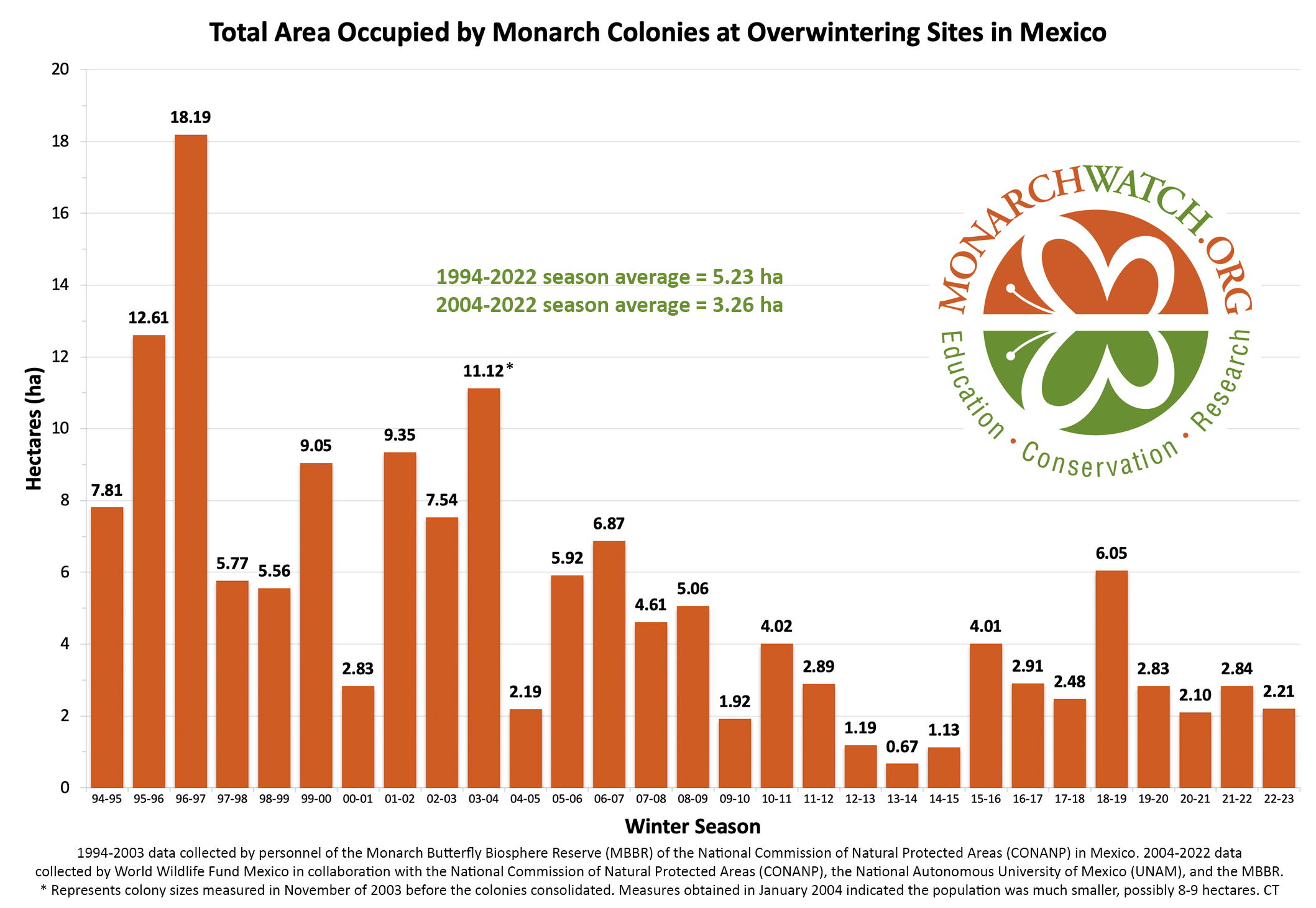

So, how do the three r’s apply to monarchs? As I have pointed out in previous articles, monarchs are remarkably resilient (Taylor, 2023A, B). The assessments of how monarchs have responded to weather events over the last 29 years have been used to ask how monarch populations might have been affected by extreme weather in the past. This approach led to two articles. One examined the probable responses to the most extreme weather events in the record that dates from 1895 and the other examined the likely outcomes of the extreme conditions during the dust bowl years from 1927–1936 (Taylor, 2023A, B). In both cases, there were several years in which it was likely that the population was as low or much lower than it was in 2013 (0.67ha). In all of these examples, monarchs recovered, again demonstrating the resilience of the species. Since many of the extremes were greater than any recorded in the last 29 years, it could be argued that these recoveries demonstrated adaptability to the climate and therefore a degree of representation. As for the last 29 years, there are numerous examples of recoveries from extreme weather events, e.g., the decline from 1999 (9.05) to 2000 (2.83) due to the drought in 2000 and the subsequent recovery in 2001 (9.35). There were similar declines and recoveries from 2003–2005 (11.12 – 2.19 – 5.92), 2008–2010 (5.06 – 1.92 – 4.02). Multiple factors were involved in the declines recorded in 2004 and 2009 (Taylor, in prep). There was also the big crash from 2011-2015 that began with the 7-month drought in Texas in 2011. In that case, the numbers, starting with 2011, were 2.89 – 1.19 – 0.67 – 1.13 – 4.01. There were significant increases in the population in each of the two years following the low (0.67) in 2013. For reference to the overwintering numbers see Figure 1. For an account of the decline and recovery from 2011–2015, see Taylor, 2021. A long explanation for what happened in the Western monarch population in the fall of 2020 with only 1,899 found at overwintering sites, to the following fall when 247K were counted can be found at Taylor, 2023C. This account represents another example of the resilience of the monarch population.

As to redundancy, which refers to the ability of a species to recover from catastrophic events, monarchs have that ability. In the last 29 years, the population has recovered from three El Niño related winter weather events that killed 75% of the butterflies in January of 2002, 70% killed in two January–February storms in 2004 and 40% in an early March storm in 2016 (Brower, et al., 2004, Brower, et al., 2017, Taylor, 2004). The severity of those storms was reflected in the post storm recovery of Monarch Watch tags from dead monarchs. These tags had been applied the previous fall migration. While tag recoveries typically number 400–600, the tags recovered after these storms numbered 3,331, 3,127, and 1,798 respectively. The monarch populations were lower in the year following each of these events (2002, 2004, 2016) but increased again in 2003 and 2005 and decreased only slightly from 2016 to 2017 (2.91 – 2.48). Thus, in each case, while the catastrophic mortality was severe, the population recovered in the second year or the following year. These are remarkable examples of the ability of the monarch population to recover following episodes of mass mortality.

The representation/adaptability/ecological role for monarchs is more nuanced. To some extent monarchs are pollinators and to another they are food for other species, but these roles are minor in the sense of representation. Monarchs cannot be described as a keystone species. In another sense, they are vulnerable since they are dependent on milkweeds as hosts for their larvae. Thus, if there are no milkweeds, there are no monarchs. Further, they show little capacity to explore alternative hosts in the Apocynaceae. Fortunately, milkweeds are diverse and widespread and monarchs are sufficiently adaptable to utilize at least 30 of the more than 70 species of milkweeds in the United States. A counter to concerns about habitat loss is our ability to propagate and restore milkweeds in habitats from which they have been extirpated. In the sense of representation, monarchs are adaptable, in that, if we create habitats, they will find them. Further, monarchs which were originally a species limited to the Americas, are now a pan-tropical species having adapted to a wide range of subtropical and tropical habitats following the introductions of several milkweed species. These examples surely speak to adaptability.

Curiously, though the three Rs are at the core of SSAs, they are only mentioned in passing in the SSA of 2020 (FWS, 2020, see pp 12-13). There was no discussion or analysis of how these criteria applied to monarchs even though all of the evidence outlined above was readily available at that time (except for the recovery in the West from 2020 to 2021). The data cited above, and more, should surely be incorporated into the SSA being prepared for the pending listing decision.

The silent partner in the push to have monarchs regulated is their cultural value. They are an iconic species. Their migration is remarkable. They are a species of wonder with a remarkable capacity to traverse a continent. Their beauty, and accessibility, along with charisma, generate emotional responses like no other insect. They are part of our heritage and reminders that we are the stewards of their fate being that we dominate the landscape and how it is used or misused. Biologically, they are an extraordinary example of the drive to survive and reproduce. Much remains unknown of how they respond to the physical cues in the environment and how those cues are processed in a manner that leads to behavioral responses. They are a model species for this research area. None of these considerations can be part of the SSA, yet they heighten the concerns about the need to sustain the monarch migration.

References

Anderson, R. S., 2017. Co-extinction: The Case of the American Chestnut and the Greater Chestnut Weevil (Curculio caryatrypes). https://nature.ca/en/co-extinction-and-the-case-of-american-chestnut-and-the-greater-chestnut-weevil-curculio-caryatrypes/.

Brower, L. P., Williams, E. H., Jaramillo-Lopez, P., Kust, D. R., Slayback, D. A., and Ramíerz, M. I. (2017). Butterfly Mortality and Salvage Logging from the March 2016 Storm in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve in Mexico. Amer. Entomol. 63, Issue 3, 151–164.

Brower, L.P., D.R. Kust, E. Rendon-Salinas, E. G. Serrano, K. R. Kust, J. Miller, C. Fernandez del Rey, and K. Pape. 2004. Catastrophic winter storm mortality of monarch butterflies in Mexico during January 2002, pp. 151–166. In K. S. Oberhauser and M. J. Solensky (eds.). The monarch butterfly: biology and conservation. Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

Fish and Wildlife Service. Monarch Butterfly Species Status Assessment (SSA) Report. September 2020. https://www.fws.gov/media/monarch-butterfly-species-status-assessment-ssa-report

Horne, G. M., R. Manderino, S. P. Jaffe. 2023. Specialist Herbivore Performance on Introduced Plants During Native Host Decline. Environmental Entomology, Volume 52, Issue 1, February 2023, Pages 88–97, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvac107

Taylor, O.R. 2004. Status of the population. Monarch Watch Update, 16 February 2004.Monarch Watch, Lawrence, Kansas. http://www.monarchwatch.org/update/2004/0318.html#4.

Taylor, O. R., 2021. Monarch population crash in 2013

https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2021/06/11/monarch-population-crash-in-2013/

Taylor, O. R., 2023A. Monarchs: Weather and population sizes in the past

https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2023/07/21/monarchs-weather-and-population-sizes-in-the-past/

Taylor, O. R., 2023B. Monarch populations during the Dust Bowl years

https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2023/07/17/monarch-populations-during-the-dust-bowl-years/

Taylor, O. R., 2003C. The Western monarch puzzle: the decline and increase in monarch numbers

https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2023/05/29/the-western-monarch-puzzle-the-decline-and-increase-in-monarch-numbers/

Figure 1. Total Area Occupied by Monarch Colonies at Overwintering Sites in Mexico.

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.