8 July 2021 | Author: Jim Lovett

This newsletter was sent via email to those who subscribe to our email updates. If you would like to receive periodic email updates from Monarch Watch, please take a moment to complete and submit the short Google Form at https://monarchwatch.org/subscribe/

Greetings Monarch Watchers!

Included in this issue:

1. Monarch Population Status

2. Monarch Watch Tagging Kits for 2021

3. Submitting Tag Data

4. Tagging Wild and Reared Monarchs

5. Monarch Waystations

6. Collect Milkweed Seed for Monarch Watch

7. Monarch Calendar Project

8. Upcoming Monarch Watch Events

9. Monarch Rearing, Tagging and Releasing Survey

10. About This Monarch Watch List

——————————————————

1. Monarch Population Status —by Chip Taylor

——————————————————

EASTERN MONARCHS

As you may recall, I was concerned about the conditions monarchs would encounter as they returned from Mexico in March due to the devastating impact of the 11-day freeze in Texas in mid-February. That led to a project to determine 1) how the vegetation recovered from the freezing conditions, 2) the plants the monarchs used for nectar and 3) the phenology of the emergence of milkweeds. Those investigations were summarized in two entries posted to the Blog:

Nectar plants used by monarchs during March in Texas

https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2021/05/25/nectar-plants-used-by-monarchs-during-march-in-texas/

Monarchs and the freeze in Texas

https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2021/06/01/monarchs-and-the-freeze-in-texas/

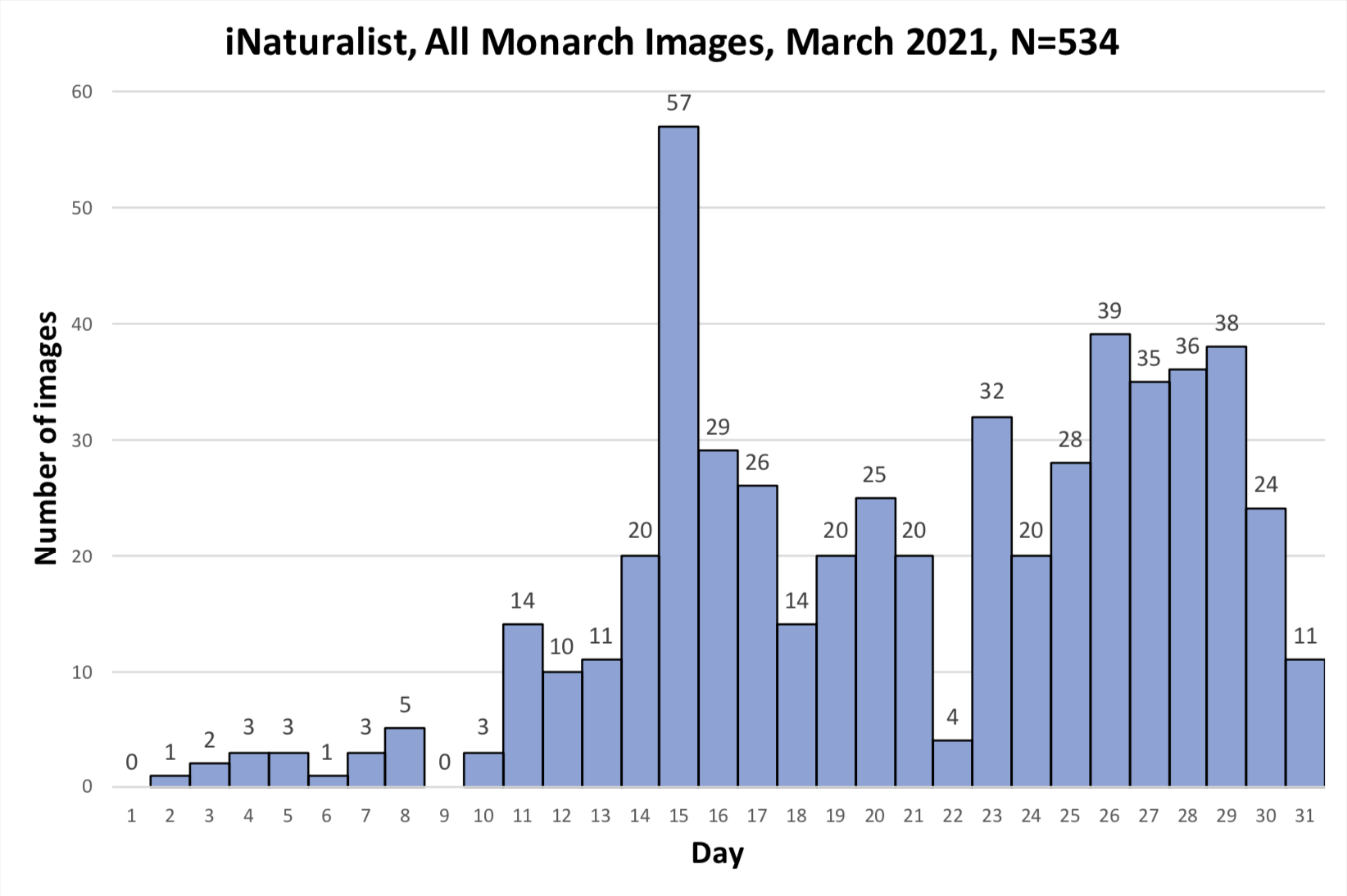

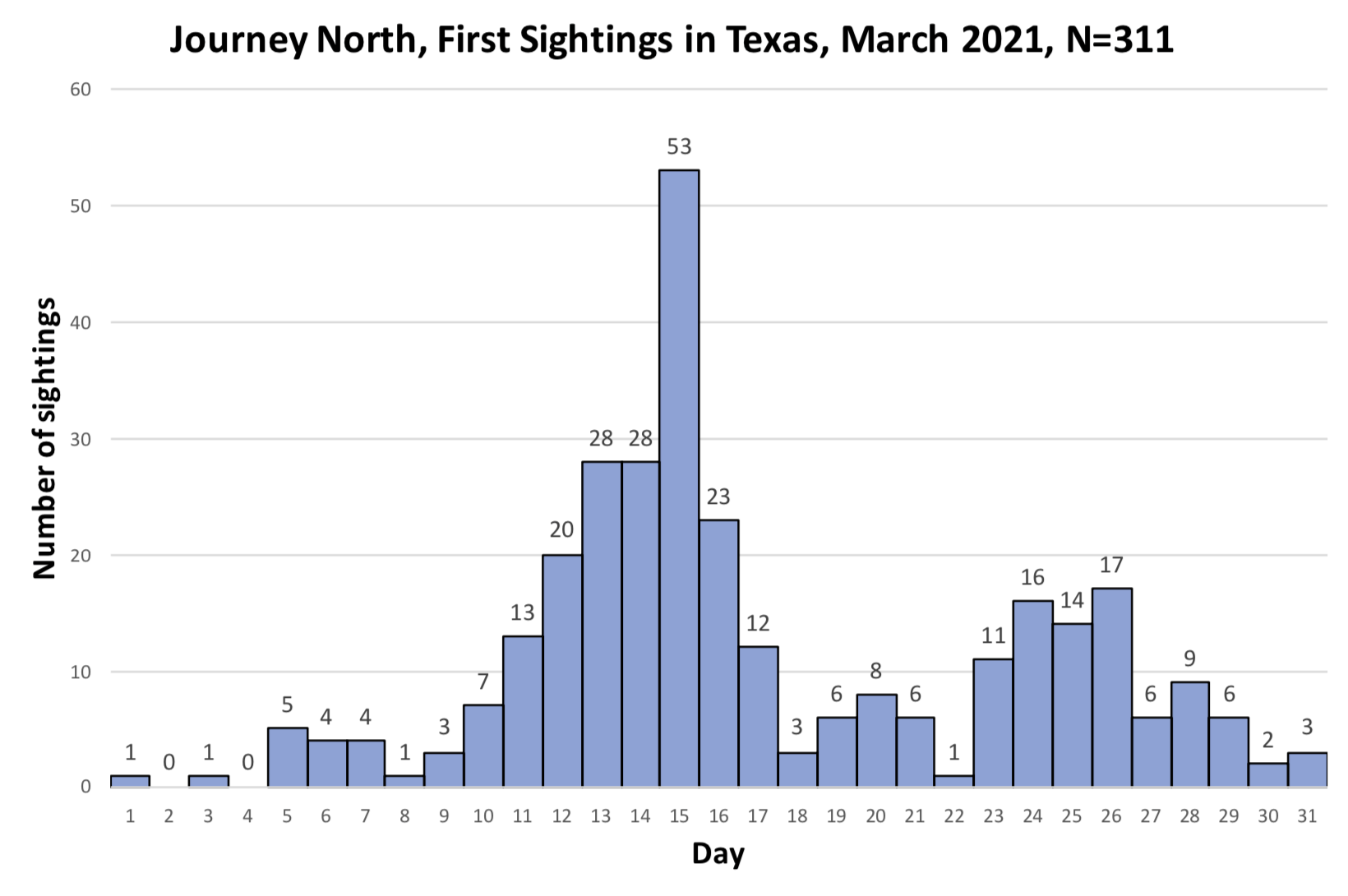

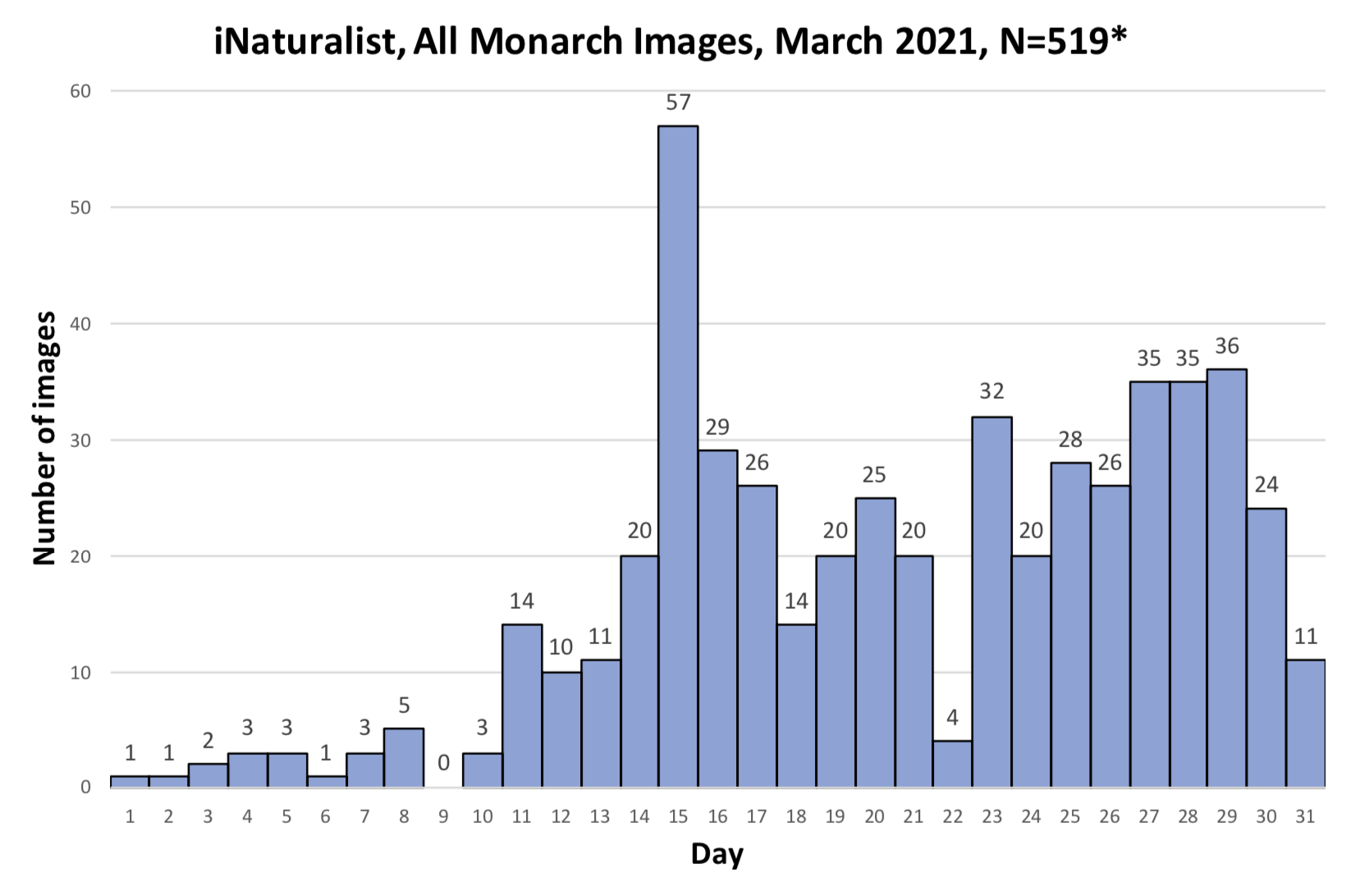

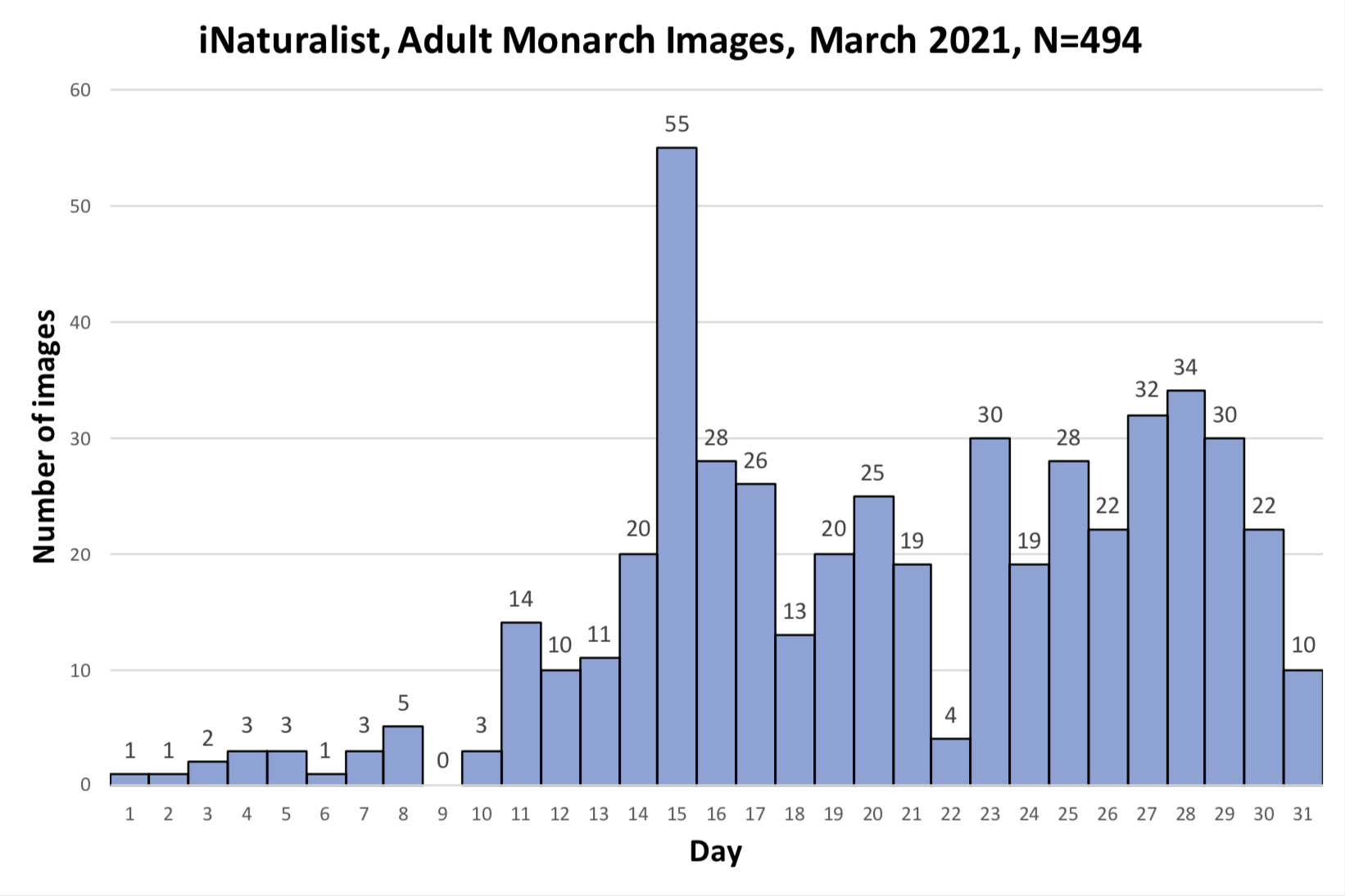

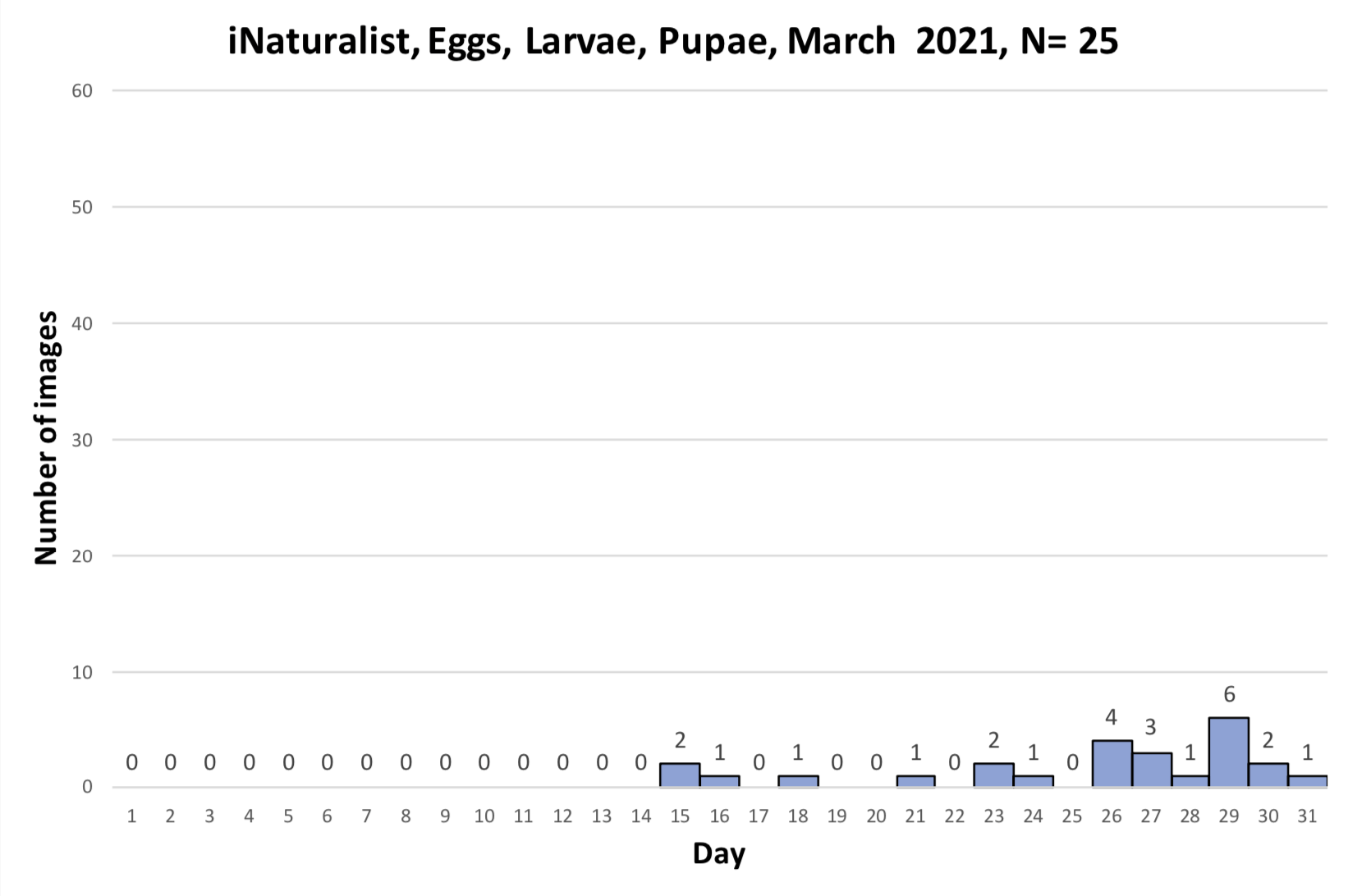

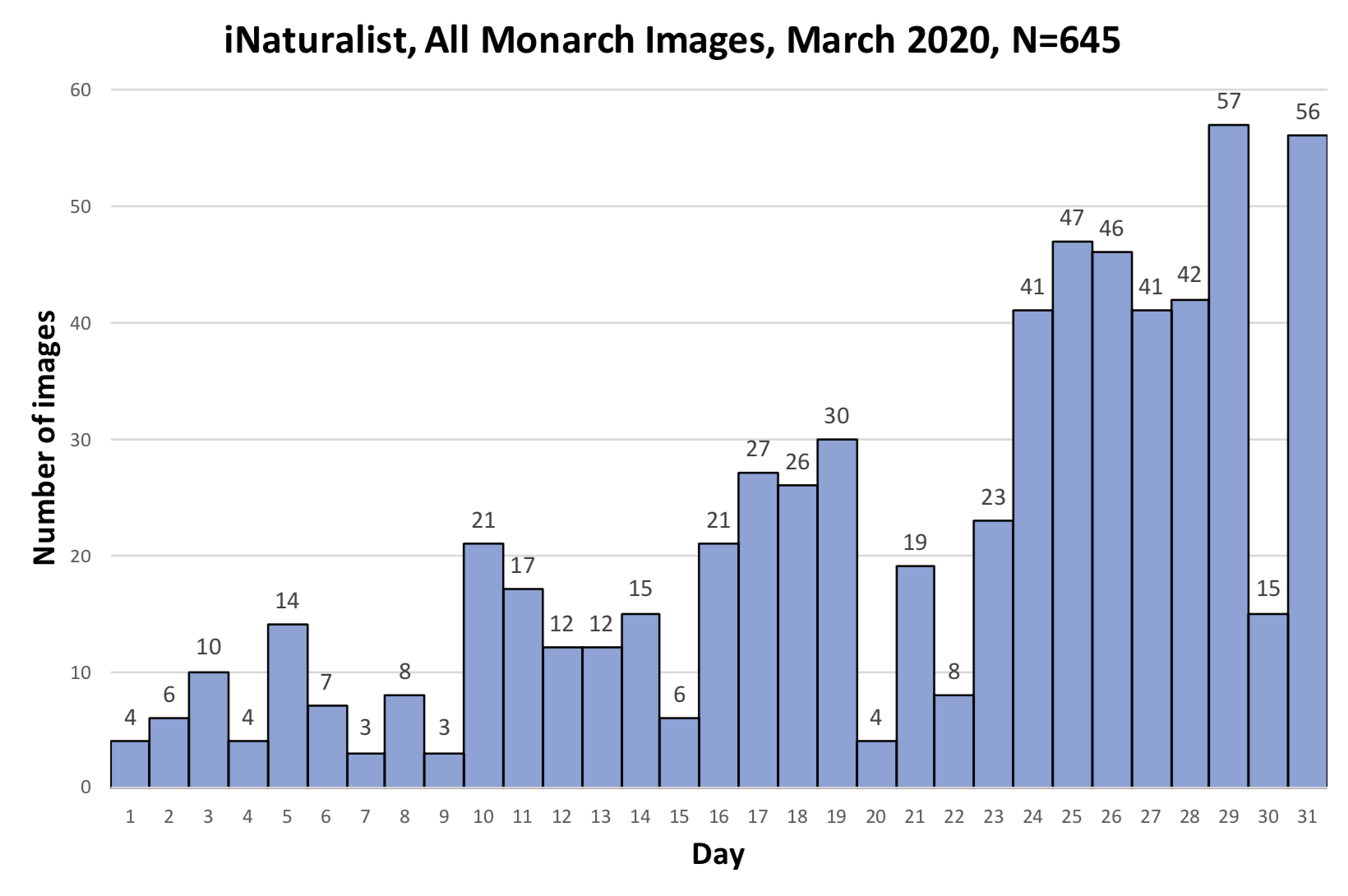

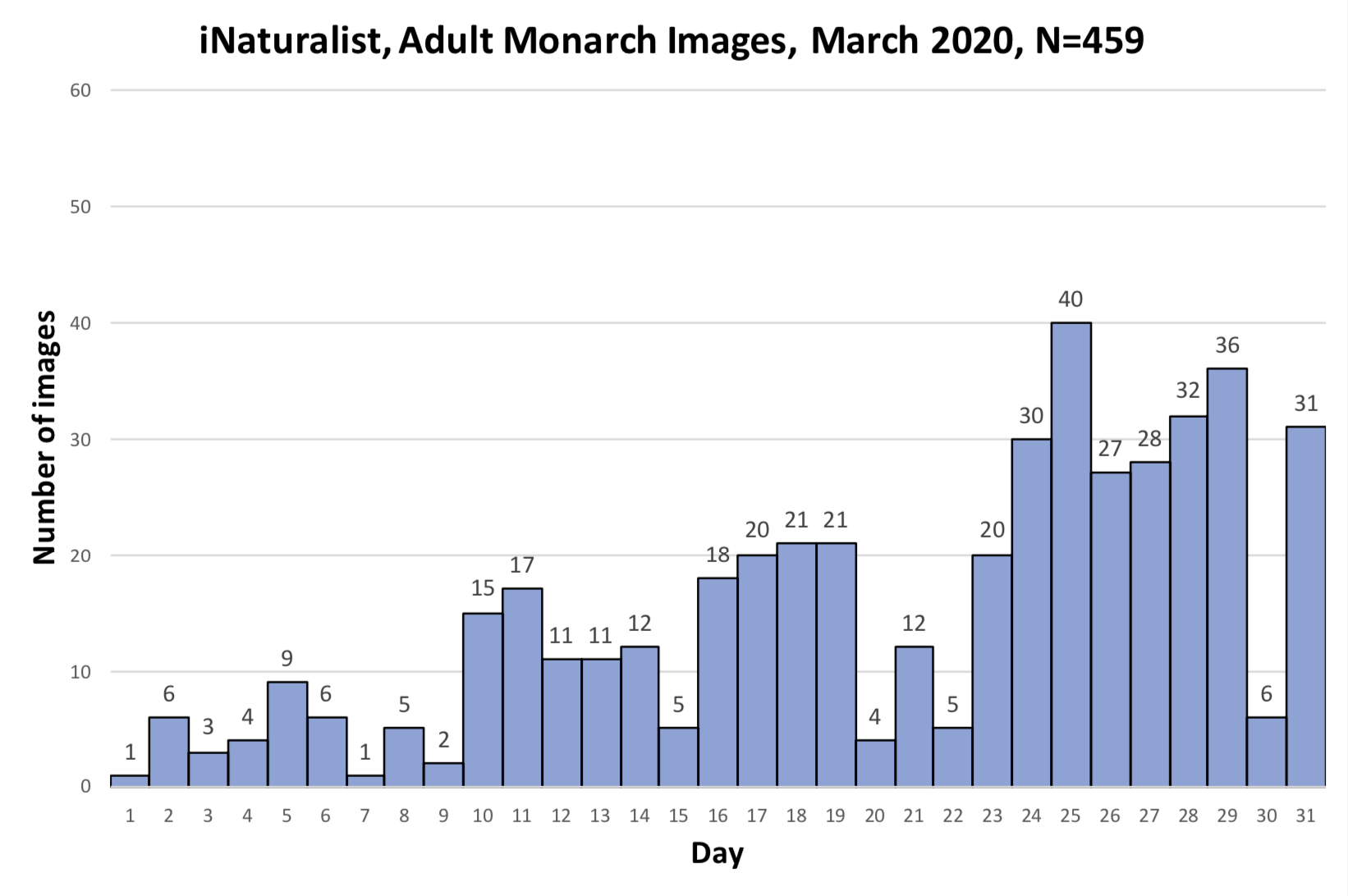

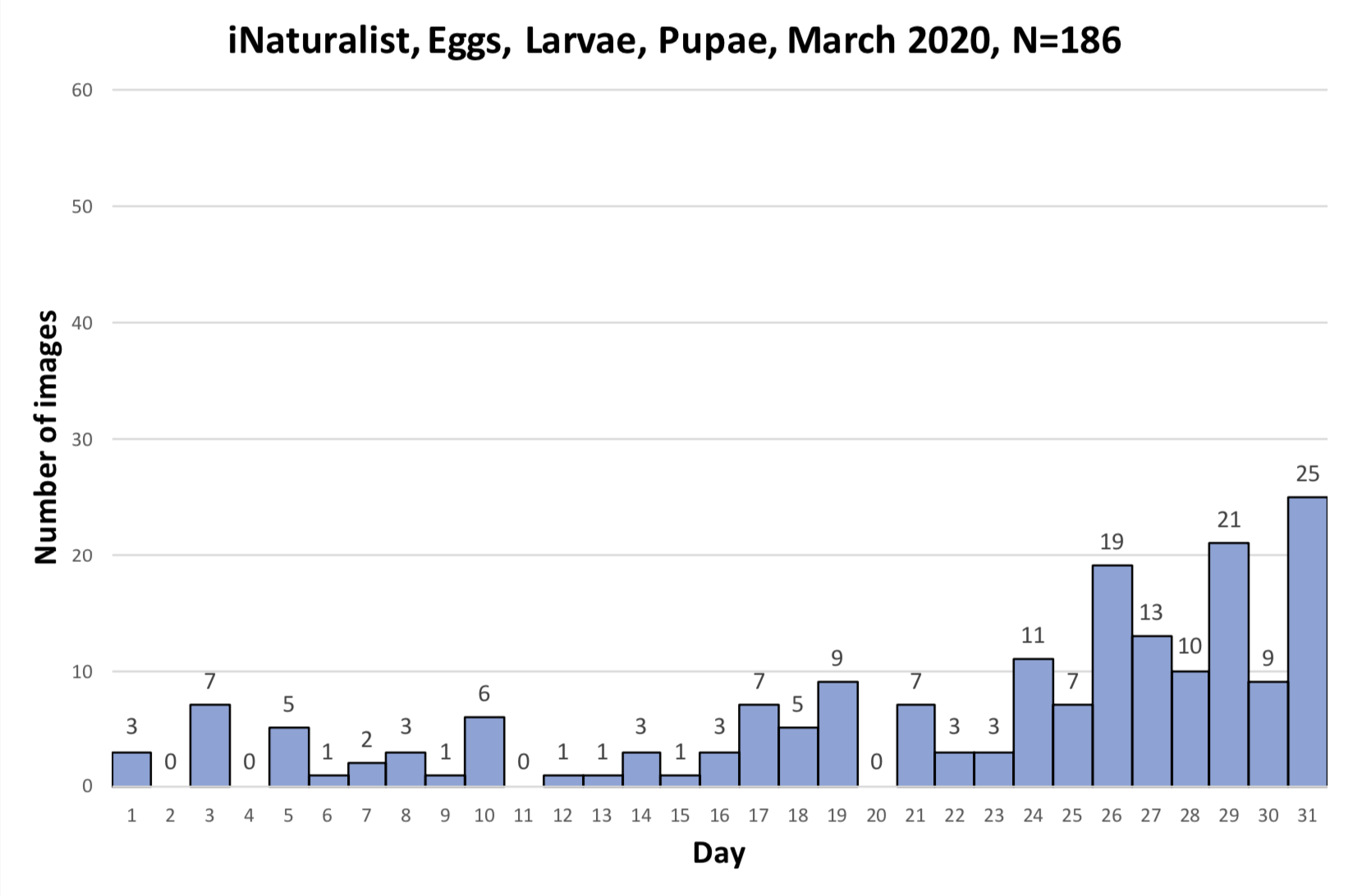

Overall, monarchs seemed to find enough nectar and milkweeds to get the breeding season underway. The next question was where most of the eggs were laid by returning females and would that egg-laying lead to the production of a small, medium or large number of first-generation offspring. Although some of the returning monarch moved north before the appearance of milkweeds, my sense, based on numerous reports from mid to north Texas, was that the majority of eggs were laid in these regions. While the distribution of eggs looked favorable, the larvae still have to reach the adult stage and those first-generation offspring then have to recolonize the breeding areas to the north.

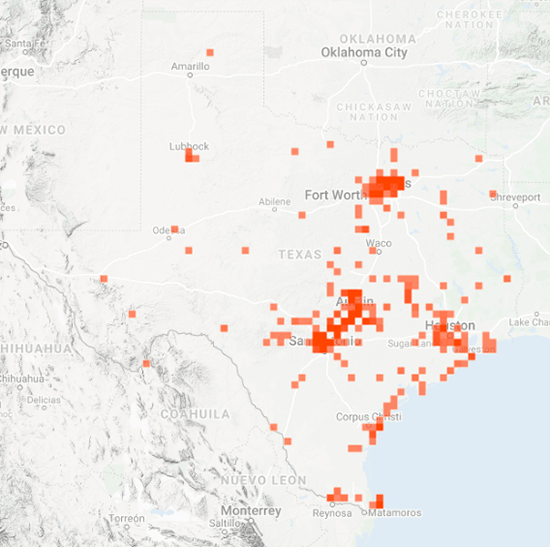

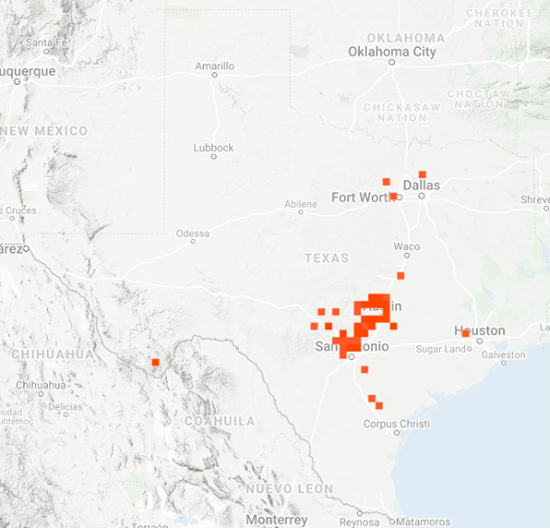

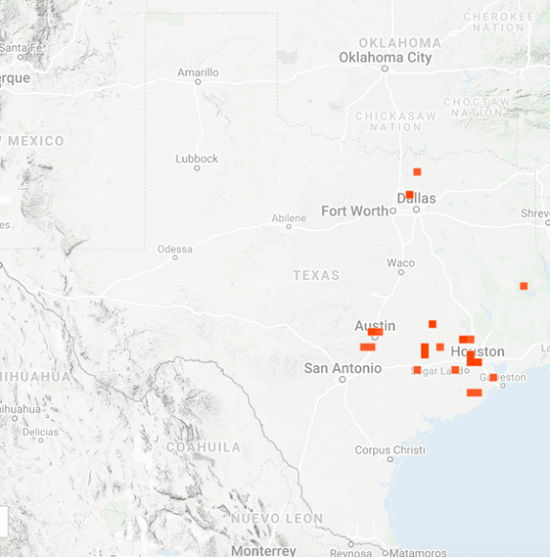

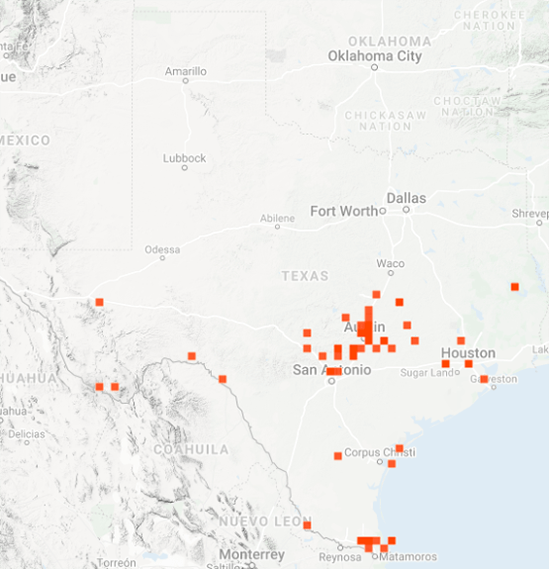

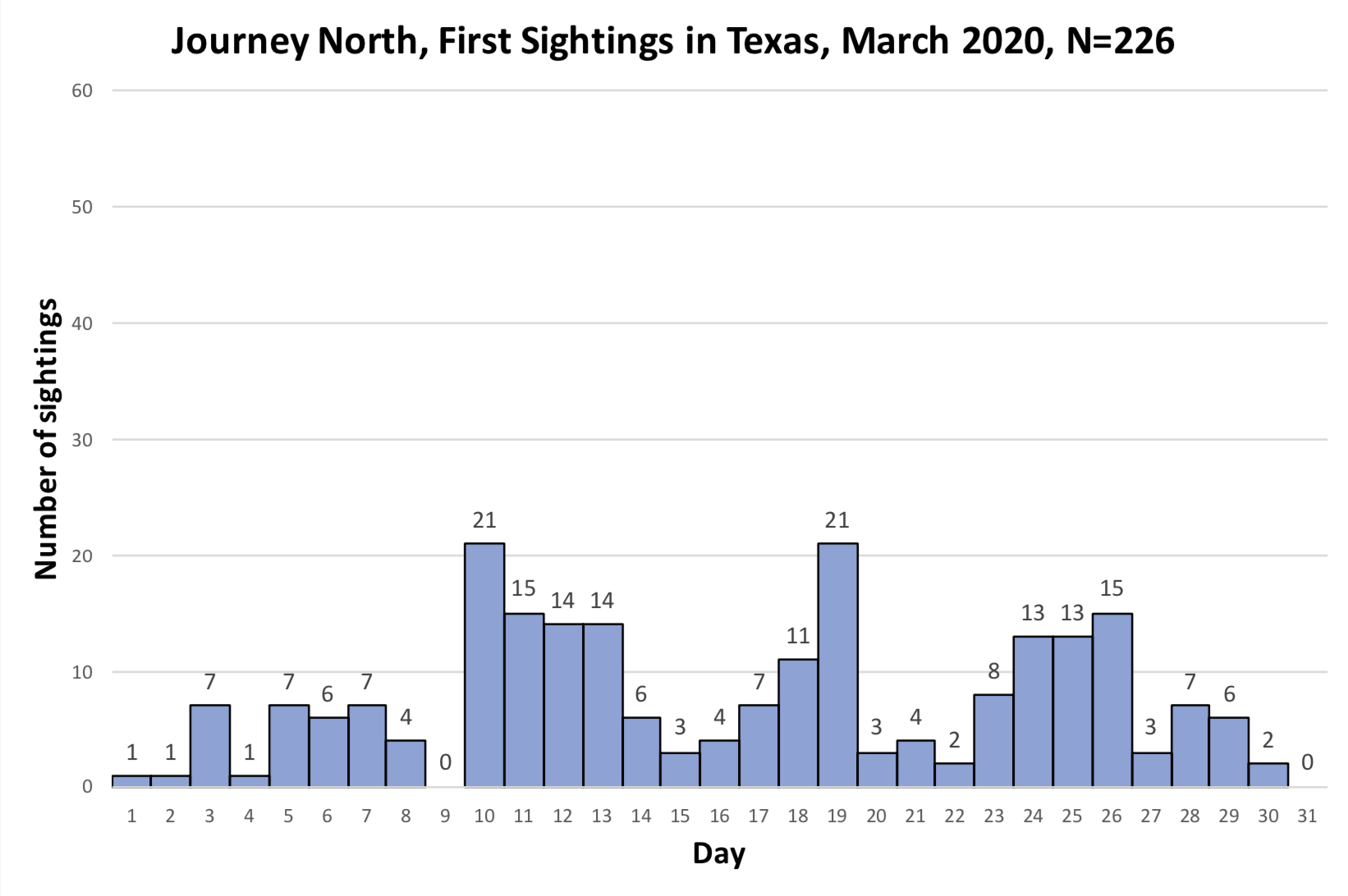

To assess the size of the first generation and success of the recolonization, I rely on the first sightings posted to Journey North. The number of first sightings grows from year to year as more people post their sightings. Nevertheless, I can still get a sense of the year- to-year differences based on the timing of the sightings and their number. To assess what has happened this year from late April to early June, I examined the Journey North first sightings maps from 2010-2021. Tentatively, it looks like the recolonization of the summer breeding range this year is the best ever. I say “tentatively” because I have to look at the data more closely. But it does look like this will be a good year for monarchs.

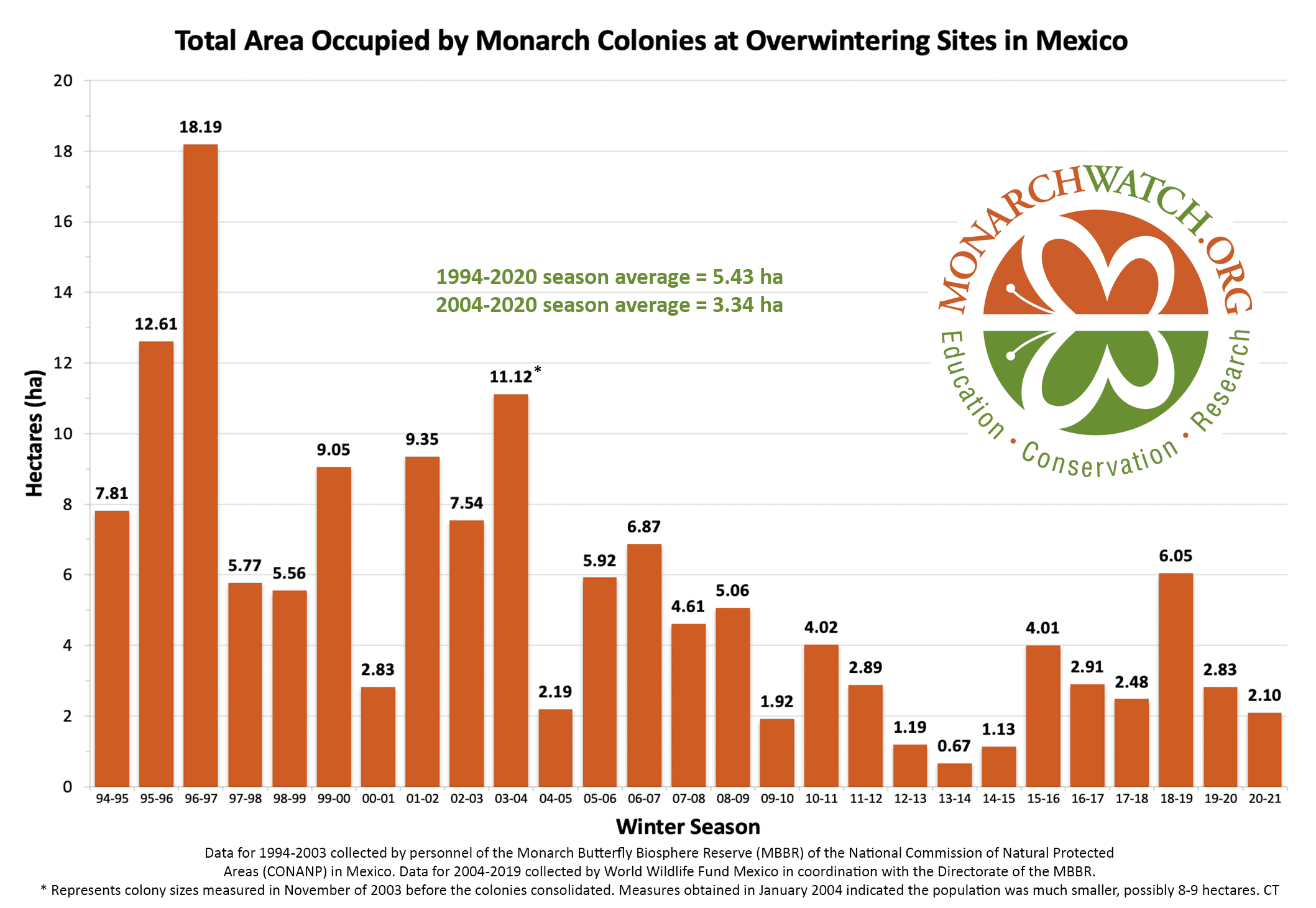

As of late June, it looks like the recolonization could produce an overwintering population ranging from 2-6 hectares with a real potential to be on the high end of that range. To be at the high end of the range, temperature and rainfall have to be within +/-1.5 degrees and +/-2 inches of the long-term means from now through September. While this prediction holds for most of the range, it is particularly important for the conditions to be close to the long-term average for the Upper Midwest, since it is this region that contributes the greatest number of monarchs to the overwintering population.

For more on the influence of environmental conditions on the development of the populations each year, see this recent blog post:

Monarch population crash in 2013

https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2021/06/11/monarch-population-crash-in-2013/

WESTERN MONARCHS

This spring, Monarch Watch announced a partnership with a California nursery to facilitate distribution of native milkweeds. Californians stepped up and we are currently out of milkweeds for the state but will make an announcement when availability returns. If you are interested in donating native milkweed seed to this cause, please see the “Collect Milkweed Seed for Monarch Watch” item below. Thank you!

Google is taking steps to help address the threat facing California’s monarch butterflies:

Doing our part for California’s monarch butterflies

https://blog.google/outreach-initiatives/sustainability/monarch-butterflies-california/

Review published in Conservation Science and Practice:

Are eastern and western monarch butterflies distinct populations?

A review of evidence for ecological, phenotypic, and genetic differentiation and implications for conservation

Micah G. Freedman, Jacobus C. de Roode, Matthew L. Forister, Marcus R. Kronforst, Amanda A. Pierce, Cheryl B. Schultz, Orley R. Taylor, Elizabeth E. Crone

https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/csp2.432

From the abstract:

In this review, we focus on phenotypic and genetic differentiation between eastern and western monarchs, with the goal of informing researchers and policy-makers who are interested in monarch conservation. Eastern and western monarchs occupy distinct environments and show some evidence for phenotypic differentiation, particularly for migration-associated traits, though population genetic and genomic studies suggest that they are indistinguishable from one another.

——————————————————

2. Monarch Watch Tagging Kits for 2021

——————————————————

Monarch tagging continues to be an important tool to help us understand the monarch migration and annual cycle – a long-term record is crucial to understand the dynamics of such complex natural phenomena. Tags for the 2021 fall tagging season are available and we will start shipping preorders out later this month, ahead of the migration in your area. If you would like to tag monarchs this year, please order your tags soon as they are going fast! Tagging Kits ordered after July 21st should arrive within 7–10 days but priority will be given to preorders and areas that will experience the migration first.

Monarch Watch Tagging Kits are only shipped to areas east of the Rocky Mountains. Each tagging kit includes a set of specially manufactured monarch butterfly tags (you specify quantity), a data sheet, tagging instructions, and additional monarch / migration information. Tagging Kits for the 2021 season start at only $15 and include your choice of 25, 50, 100, 200, or 500 tags.

Monarch Watch Tagging Kits and other materials (don’t forget a net!) are available via the Monarch Watch Shop online at https://shop.monarchwatch.org – where each purchase helps support Monarch Watch.

2021 datasheets and instructions will also available online soon via the Monarch Tagging Program page at https://monarchwatch.org/tagging

Tagging should begin in early to mid-August north of 45N latitude (e.g. Minneapolis), late August at other locations north of 35N (e.g., Oklahoma City, Fort Smith, Memphis, Charlotte) and in September and early October in areas south of 35N latitude. See a map and a table with expected peak migration dates on the Monarch Tagging Program page at the link above.

——————————————————

3. Submitting Tag Data

——————————————————

Thousands of you have submitted your 2020 season tag data to us by mail or via our online submission form – thank you! We are still receiving data sheets and if you haven’t submitted your data yet (for 2020 or even previous years) it is not too late. Please review the “Submitting Your Tagging Data” information on the tagging program page then send us your data via the Tagging Data Submission Form.

Complete information is available at https://monarchwatch.org/tagging if you have questions about submitting your data to us and we have conveniently placed a large “Submit Your Tagging Data” button on our homepage at https://monarchwatch.org that will take you directly to the online form.

There you can upload your data sheets as an Excel or other spreadsheet file (PREFERRED; download a template file from https://monarchwatch.org/tagging) or a PDF/image file (scan or photo).

If you have any questions about getting your data to us, please feel free to drop Jim a line anytime via JLOVETT@KU.EDU

——————————————————

4. Tagging Wild and Reared Monarchs

——————————————————

As a reminder, the following is an abbreviated version of our “Tagging wild and reared monarchs: Best practices” article posted to our Blog in 2019. The complete text of the article is available via the link below.

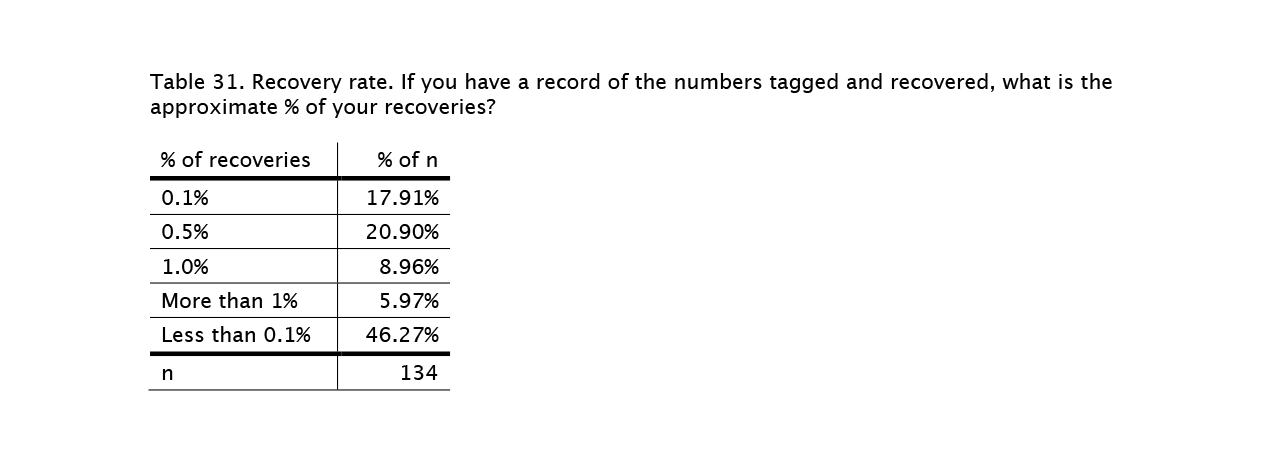

Diving into the tagging data has revealed a number of surprises such as the difference between the probability that a reared monarch will reach Mexico and the probability that a wild–tagged monarch will do so. The recovery rate is higher for wild–caught monarchs (0.9% vs 0.5%) and it is the data from the wild–caught butterflies that tell us the most about the migration. Frankly, for some analyses, we have to set the reared monarch data aside. That doesn’t mean it is not valuable, but its uses are limited.

It should be noted that for tagging data purposes, monarchs captured as adult butterflies should be reported as WILD and adult monarchs reared from the egg, larva, or pupa stage should be considered REARED.

TAGGING WILD-CAUGHT MONARCHS

For wild-caught monarchs we need to:

1. increase the number of taggers from western Minnesota and Iowa westward into Nebraska and the Dakotas to give us a more complete understanding of dynamics of the migration;

2. increase the number of wild monarchs that are tagged since these provide the most valuable data; and

3. increase the number of taggers who tag from the beginning of the tagging season in early August until the migration ends. Tagging records for the entire season will help us establish the proportion of the late–season monarchs that reach the overwintering sites. When tagging wild–caught monarchs, many taggers run out of tags well before the season ends. That’s great, but it would help us to know when all tags had been used by indicating this via the online tagging data submission form.

TAGGING REARED MONARCHS

Reared butterflies tend to average smaller than wild migrants. That difference can be reduced significantly if careful attention is given to rearing larvae under the best possible conditions. Large monarchs have the best chance of reaching Mexico, surviving the winter and reproducing in Texas. There are several reasons for this: better glide ratio, better lift with cross or quartering winds, larger fat bodies, more resistance to stress, etc. There are very few small monarchs among those that return in the spring. For those of you who prefer to rear, tag and release, we have a few suggestions:

1. Rear larvae under the most natural conditions possible.

2. Provide an abundance of living or fresh-picked and sanitized foliage to larvae.

3. Provide clean rearing conditions.

4. Plan the rearing so that the newly-emerged monarchs can be tagged early in the migratory season (10 days before to 10 days after the expected date of arrival of the leading edge of the migration in your area).

5. Tag the butterflies once the wings have hardened and release them the day after emergence if possible.

6. When it comes to tagging, tag only the largest and most-fit monarchs (see complete article for some guidelines). Records of tags applied to monarchs that have little chance of reaching Mexico add to the mass of tagging data, but do not help us learn which monarchs reach Mexico – unless the measurements, weight and condition of every monarch tagged and released is recorded. There are a few taggers who keep such detailed records and those data can be very informative. If you collect such data and are willing to share it please contact us; do not add this information to the standard tagging data sheet.

As a final note, this text is not a directive. We are not telling you what to do; rather, we are simply providing suggestions that may lead to more successful rearing and tagging efforts. The expanded version of this article is available at

Tagging wild and reared monarchs: Best practices – https://monarchwatch.org/blog/tagging-best-practices

——————————————————

5. Monarch Waystations

——————————————————

To offset the loss of milkweeds and nectar sources we need to create, conserve, and protect monarch butterfly habitats. You can help by creating “Monarch Waystations” in home gardens, at schools, businesses, parks, zoos, nature centers, along roadsides, and on other unused plots of land. Creating a Monarch Waystation can be as simple as adding milkweeds and nectar sources to existing gardens or maintaining natural habitats with milkweeds. No effort is too small to have a positive impact.

Have you created a habitat for monarchs and other wildlife? If so, help support our conservation efforts by registering your habitat as an official Monarch Waystation today!

https://monarchwatch.org/waystations

A quick online application will register your site and your habitat will be added to the online registry. You will receive a certificate bearing your name and your habitat’s ID that can be used to look up its record. You may also choose to purchase a metal sign to display in your habitat to encourage others to get involved in monarch conservation.

As of 5 July 2021, there have been 34,848 Monarch Waystation habitats registered with Monarch Watch! Texas holds the #1 spot with 2,866 habitats and Illinois (2,695), Michigan (2,572), California (2,255), Ohio (1,803), Florida (1,762), Virginia (1,572), Wisconsin (1,535), Pennsylvania (1,524) and Ontario (1,134) round out the top ten.

You can view the complete listing and a map of approximate locations via https://monarchwatch.org/waystations/registry

——————————————————

6. Collect Milkweed Seed for Monarch Watch

——————————————————

Monarch Watch continues to distribute milkweed plugs throughout the monarch range for critical habitat restoration. Please consider donating milkweed seed from wild populations for our partner nurseries to propagate.

Monarch Watch sometimes receives seed donations that perish on the way or in storage. We all want the seed to arrive alive and well-labeled, so please visit the website and read our specific instructions about collecting and donating.

Seed Collecting & Donating Guidelines:

https://monarchwatch.org/bring-back-the-monarchs/milkweed/seed-collecting/

Some areas from which we never seem to have enough of the following seed:

A. tuberosa (butterfly milkweed) from throughout its range, especially Georgia.

A. incarnata (swamp milkweed) from the eastern U.S. states.

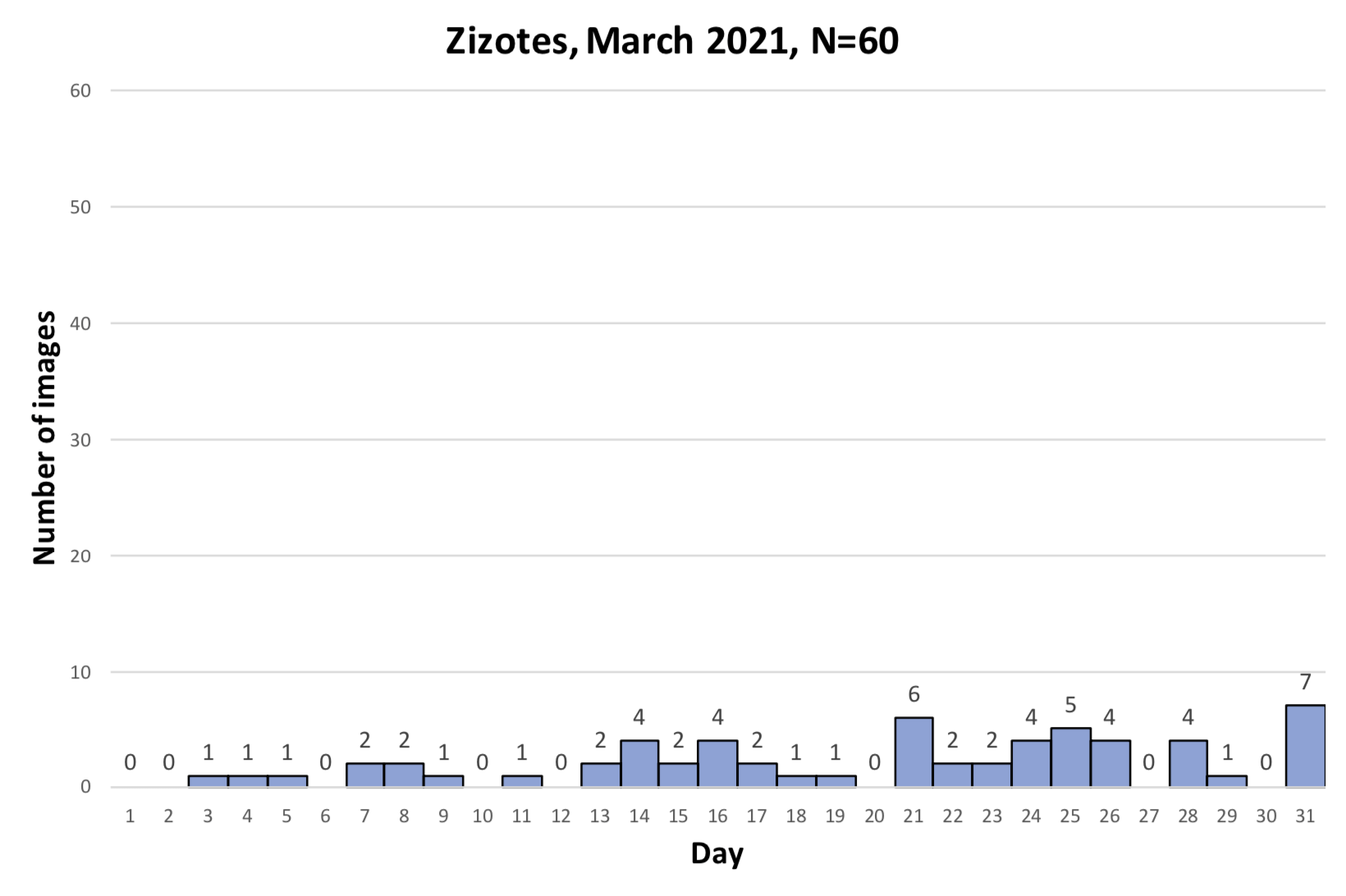

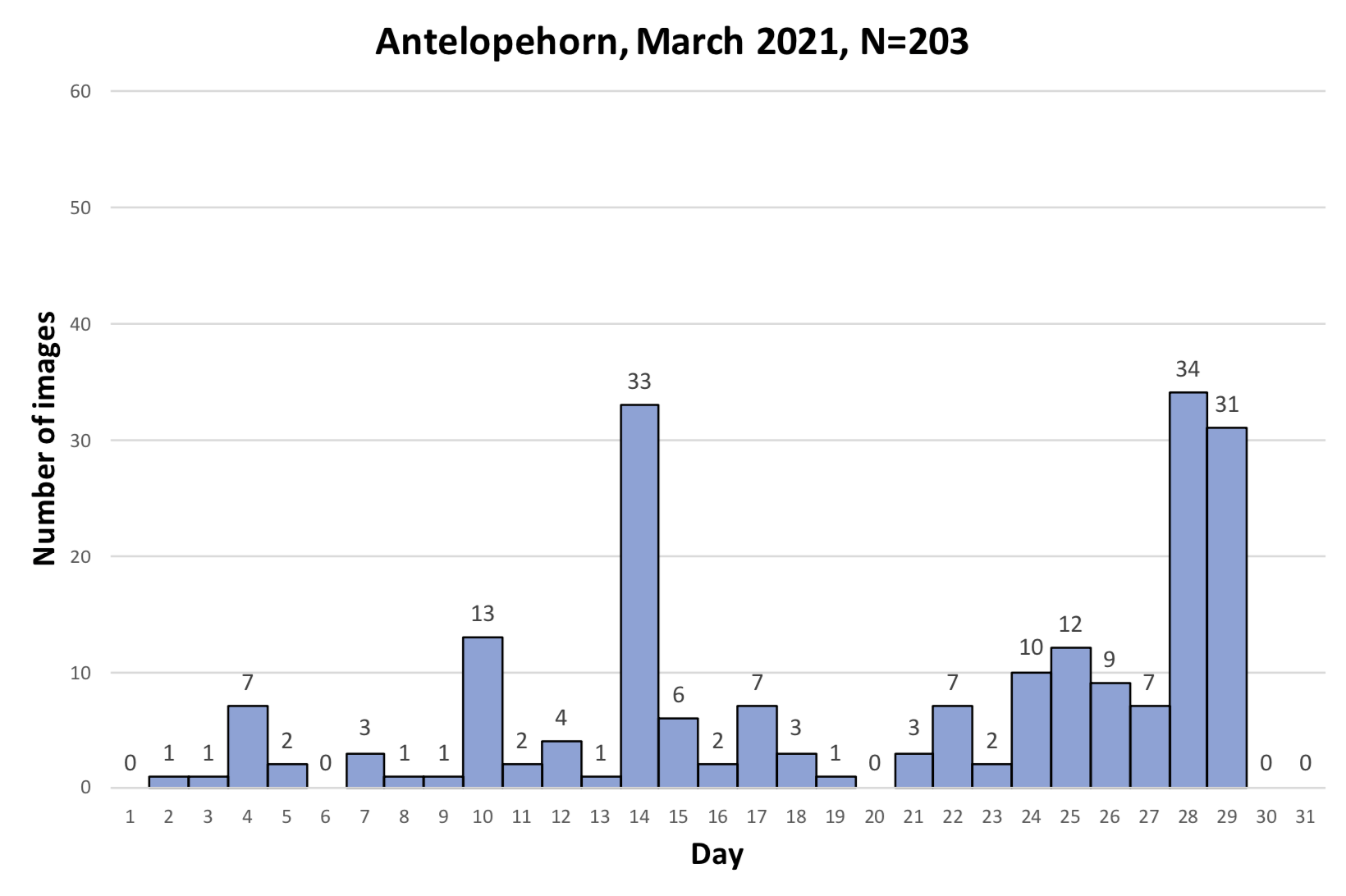

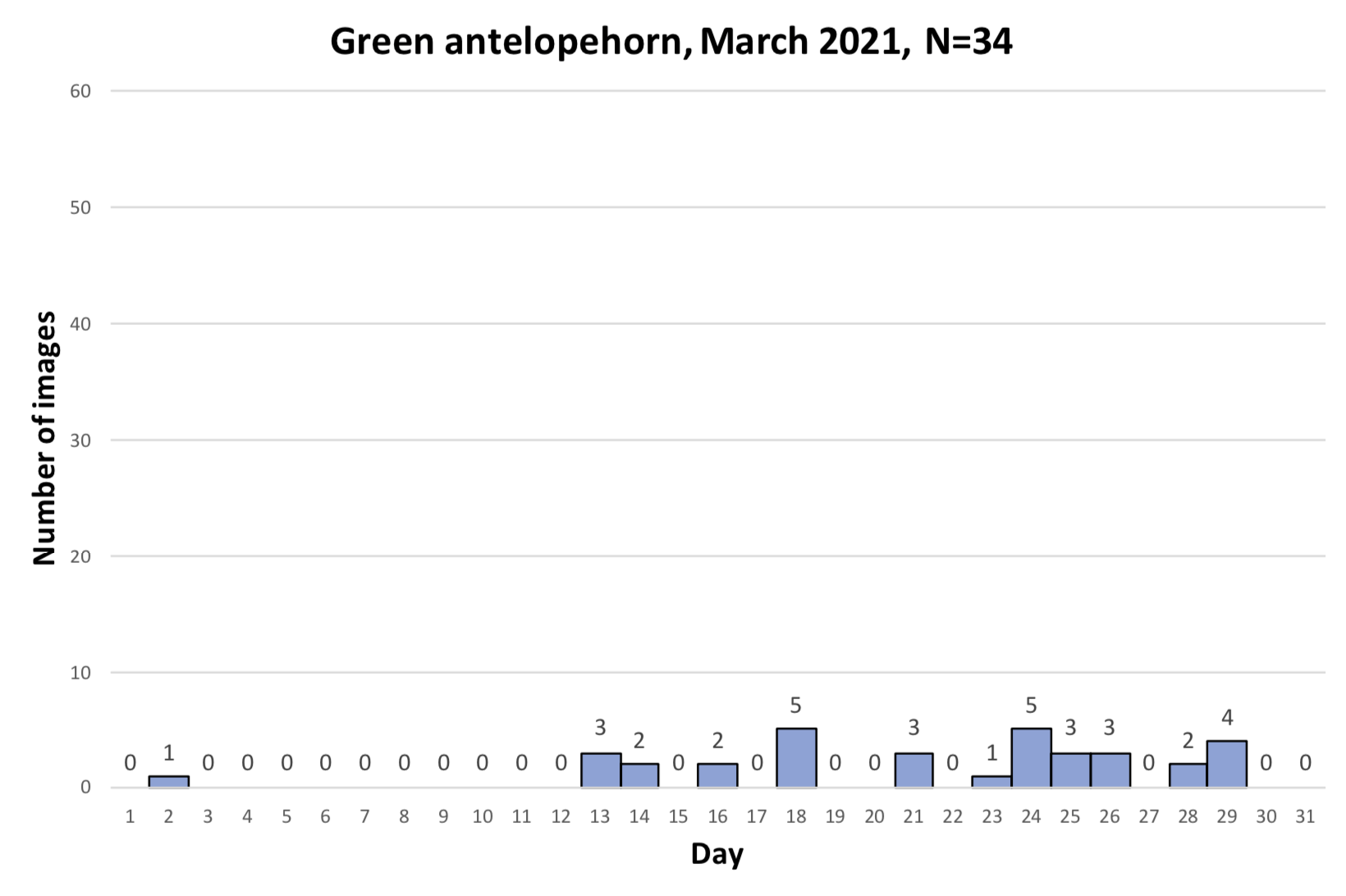

A. asperula (antelopehorn milkweed), A. viridis (green antelopehorn milkweed) and A. oenotheroides (zizotes milkweed) from Texas.

Additionally, we need this seed from Arizona and California:

A. angustifolia (arizona milkweed) from Arizona

A. californica (california milkweed) from California

A. eriocarpa (wolly pod milkweed) from California

A. erosa (desert milkweed) from California

A. speciosa (showy milkweed) from California

——————————————————

7. Monarch Calendar Project

——————————————————

For those of you participating in our Monarch Calendar project for 2021 (complete details and short registration form at https://monarchwatch.org/calendar/), observation Period 1 has ended (the final date being June 20th, for those of you north of 35N). Once you have logged all of your observations using whatever format works for you (spreadsheet, notebook, calendar, etc.), please use the appropriate online form to submit your data to us:

2021 Period 1 Submission Forms:

—————————————-

SOUTH (latitude less than 35N)

—————————————-

Form for Period 1 (15 March – 30 April): https://forms.gle/4imRF4UoVa7TZSnC6

—————————————-

NORTH (latitude greater than 35N)

—————————————-

Form for Period 1 (1 April – 20 June): https://forms.gle/KDhVfq5W5duT73vD6

The second observation period runs from 15 July–20 August in the North and 1 August–25 September in the South. As soon as the fall period ends for all locations we will send out links for submission of that data to all who have registered.

Again, complete details and a link to the short registration form are available at https://monarchwatch.org/calendar

——————————————————

8. Upcoming Monarch Watch Events

——————————————————

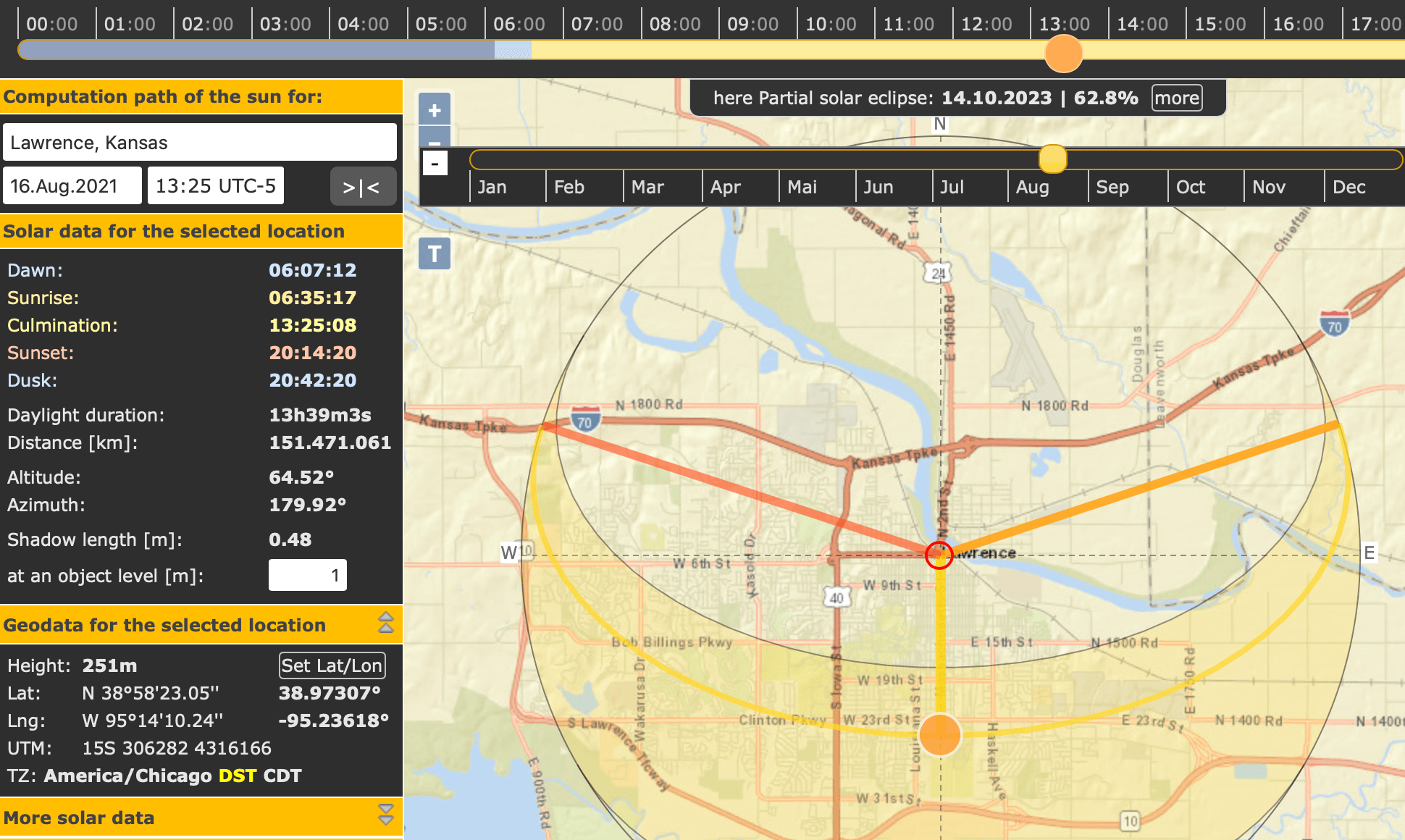

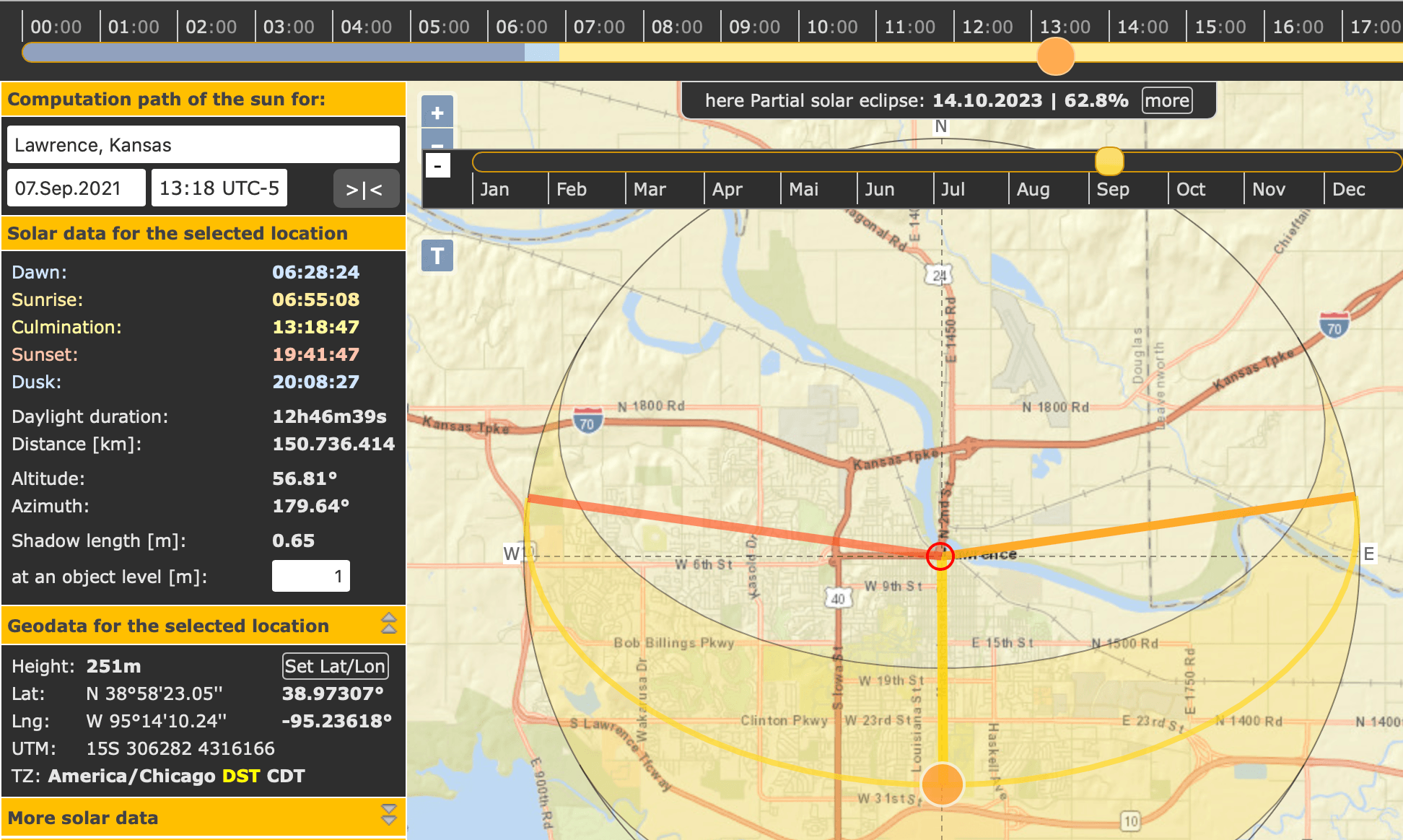

We are tentatively planning to host our annual fall events this year with some changes to the Fall Open House (it will be a shorter outdoor-only event). The tagging has always been an outdoor event so should be similar to previous years. If you’ll be in the Lawrence, Kansas area in September, we’d love for you to join us so mark your calendars and stay tuned to our website, emails and social media for additional details next month.

Monarch Watch Fall Open House (Free event)

EVENT CANCELED

Lawrence, Kansas

Monarch Watch Tagging Event (Free event)

Saturday, September 18, 2021

Baker Wetlands Discovery Center

Lawrence, Kansas

——————————————————

9. Monarch Rearing, Tagging and Releasing Survey

——————————————————

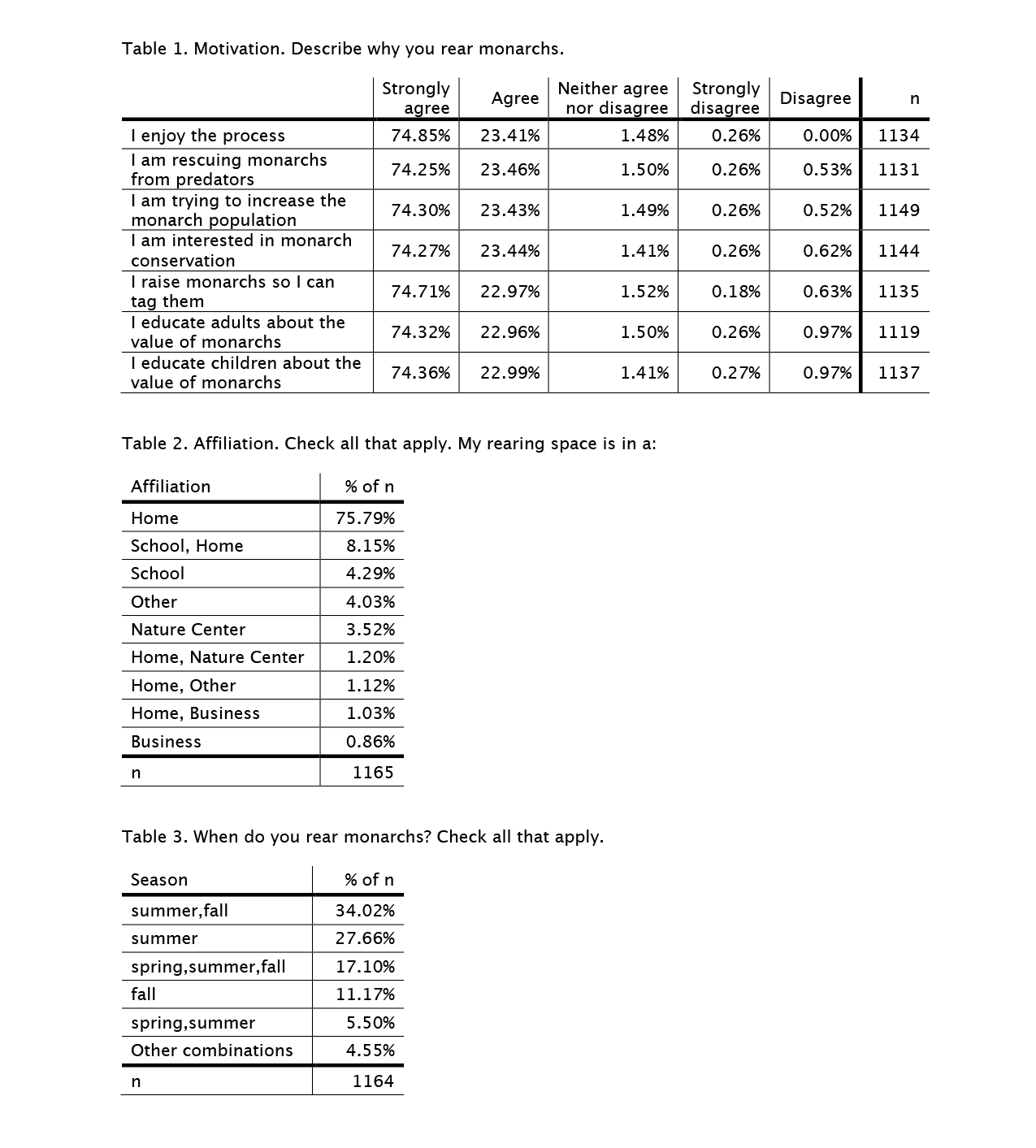

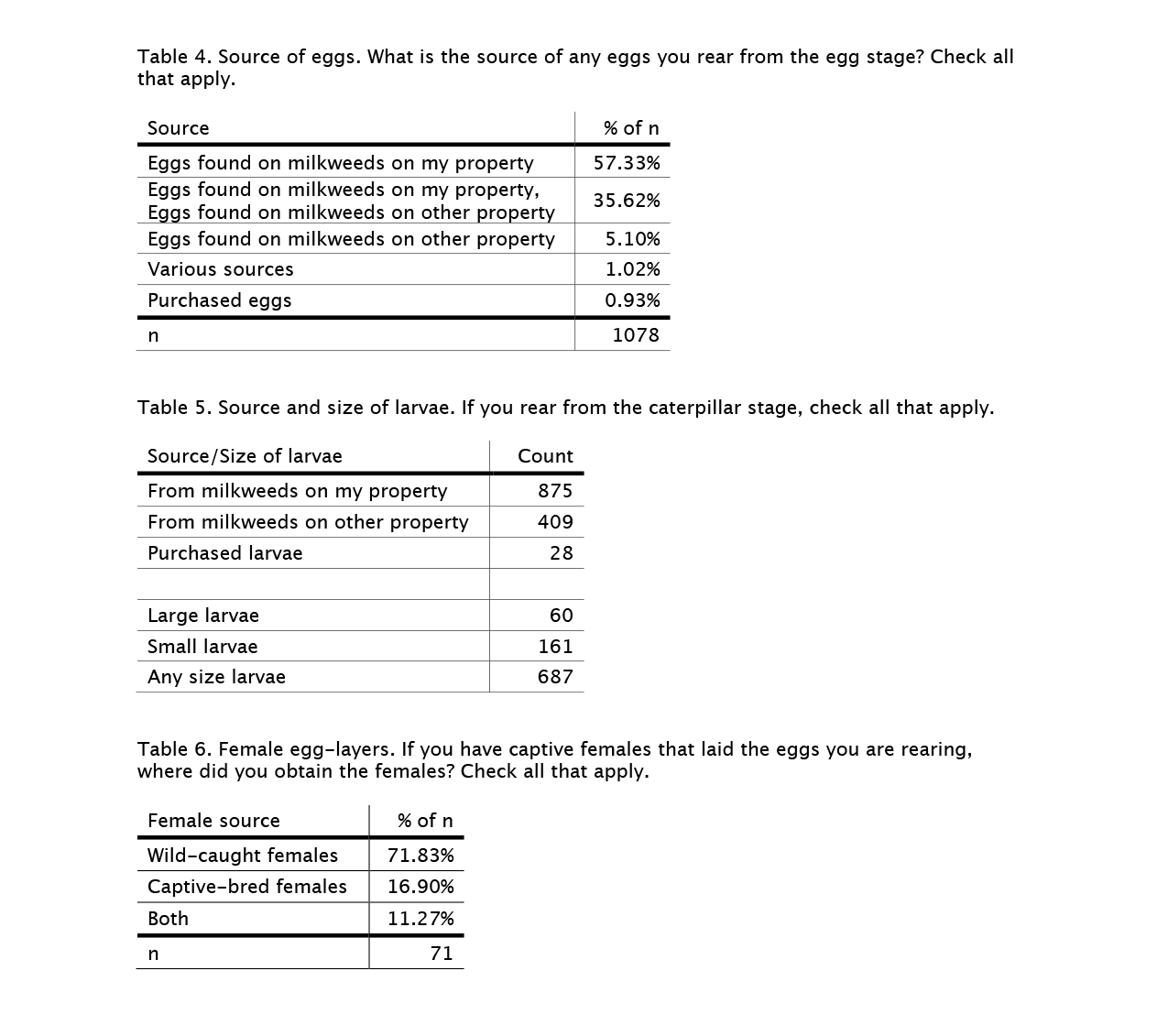

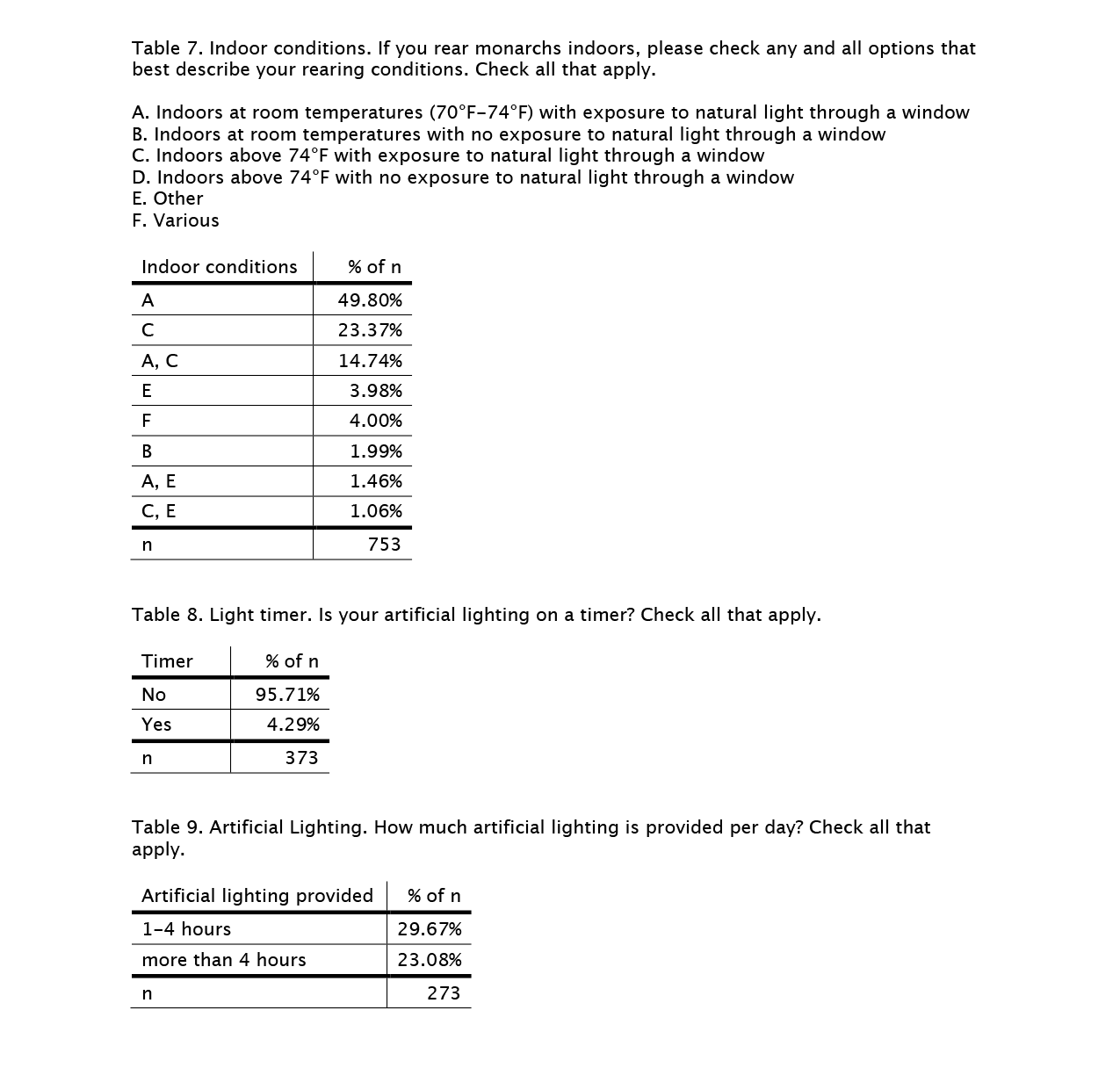

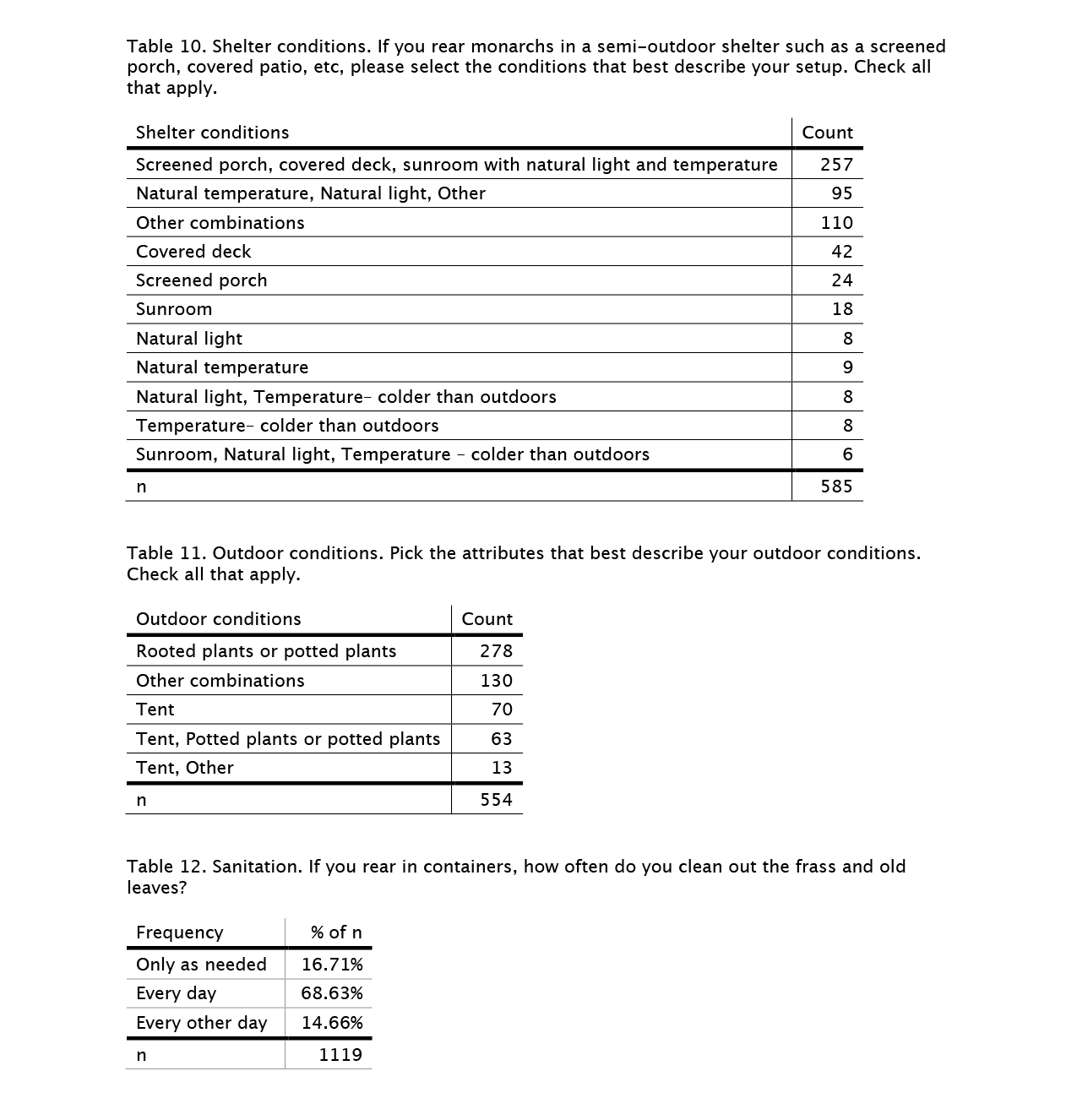

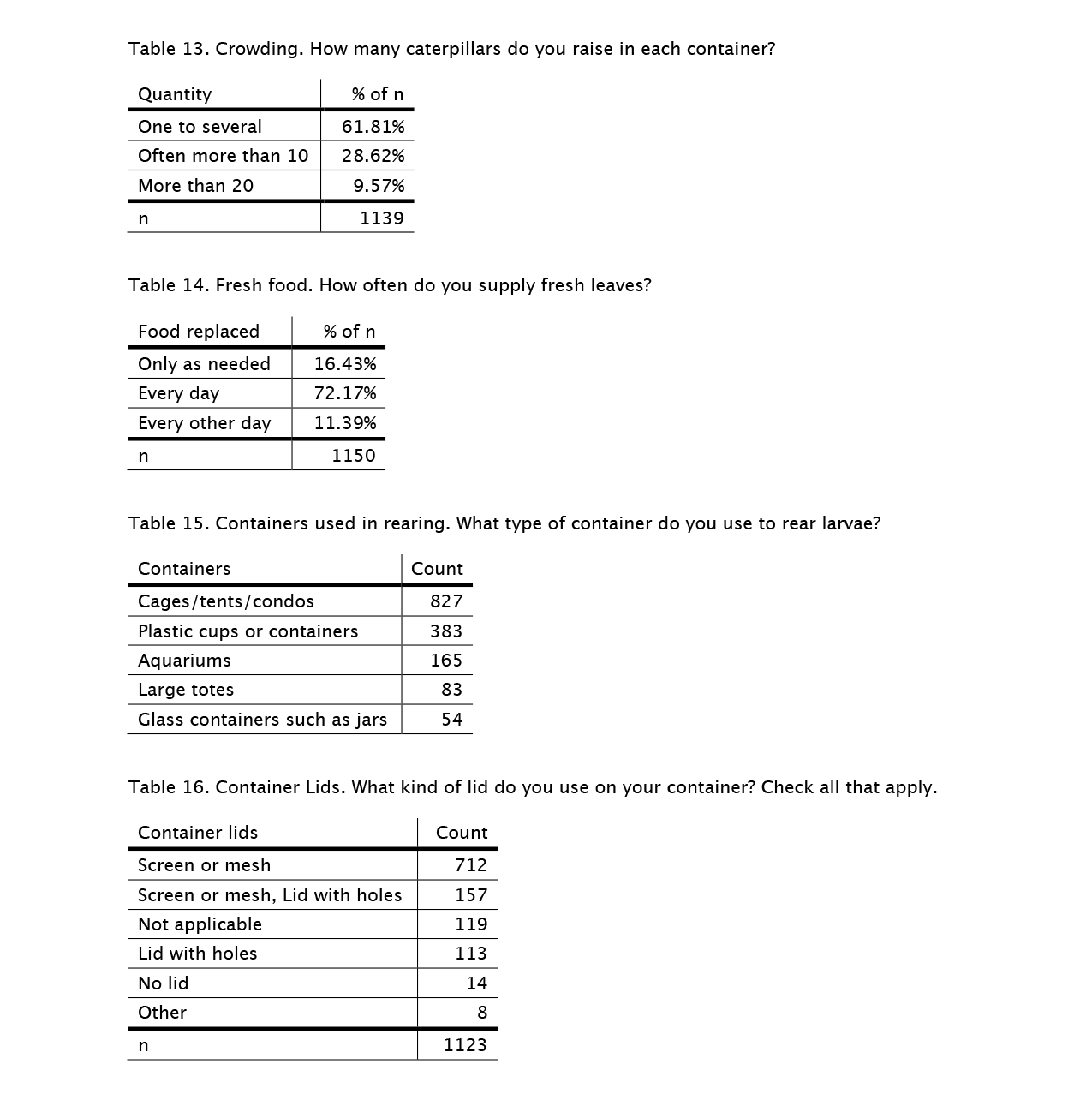

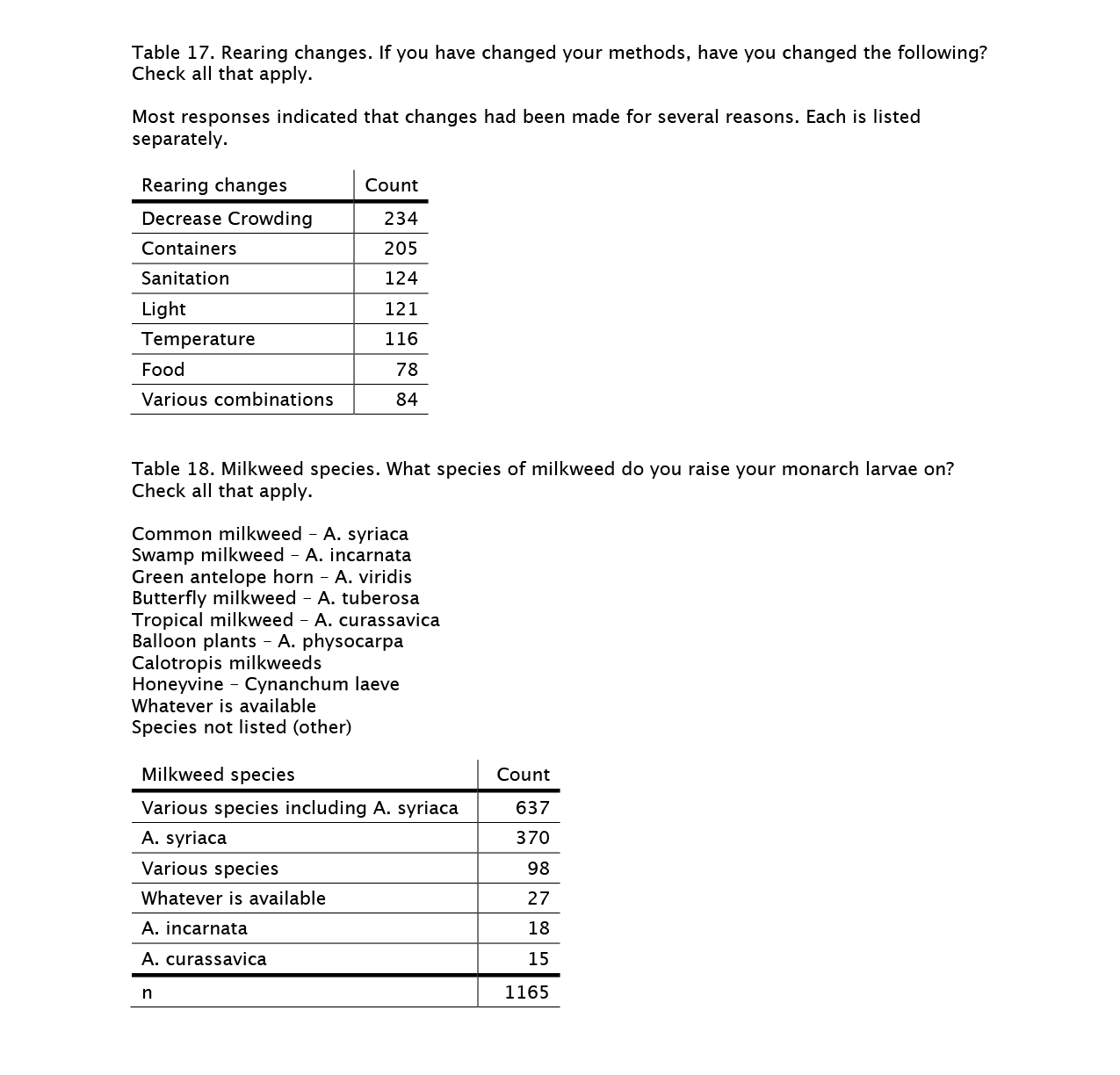

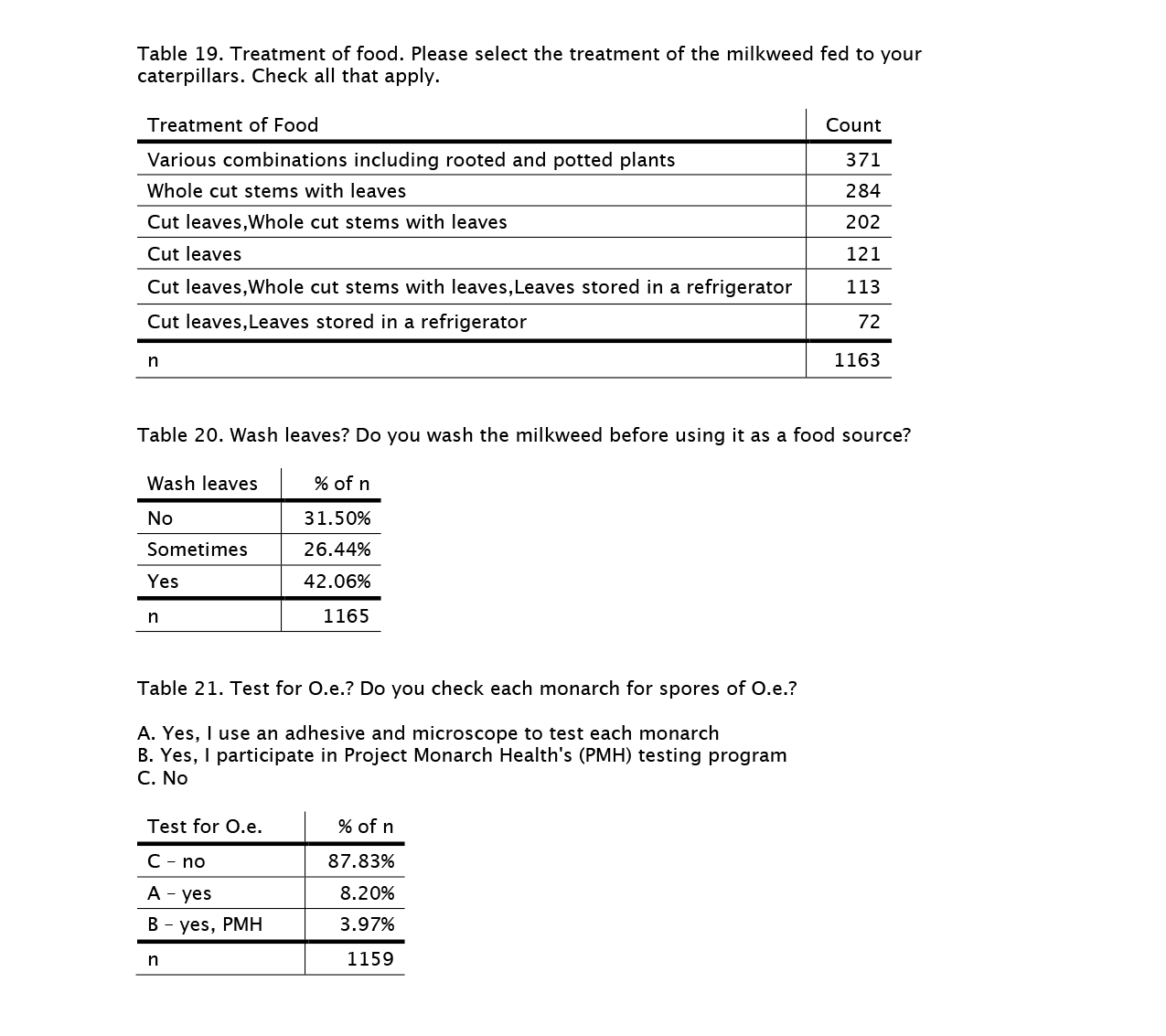

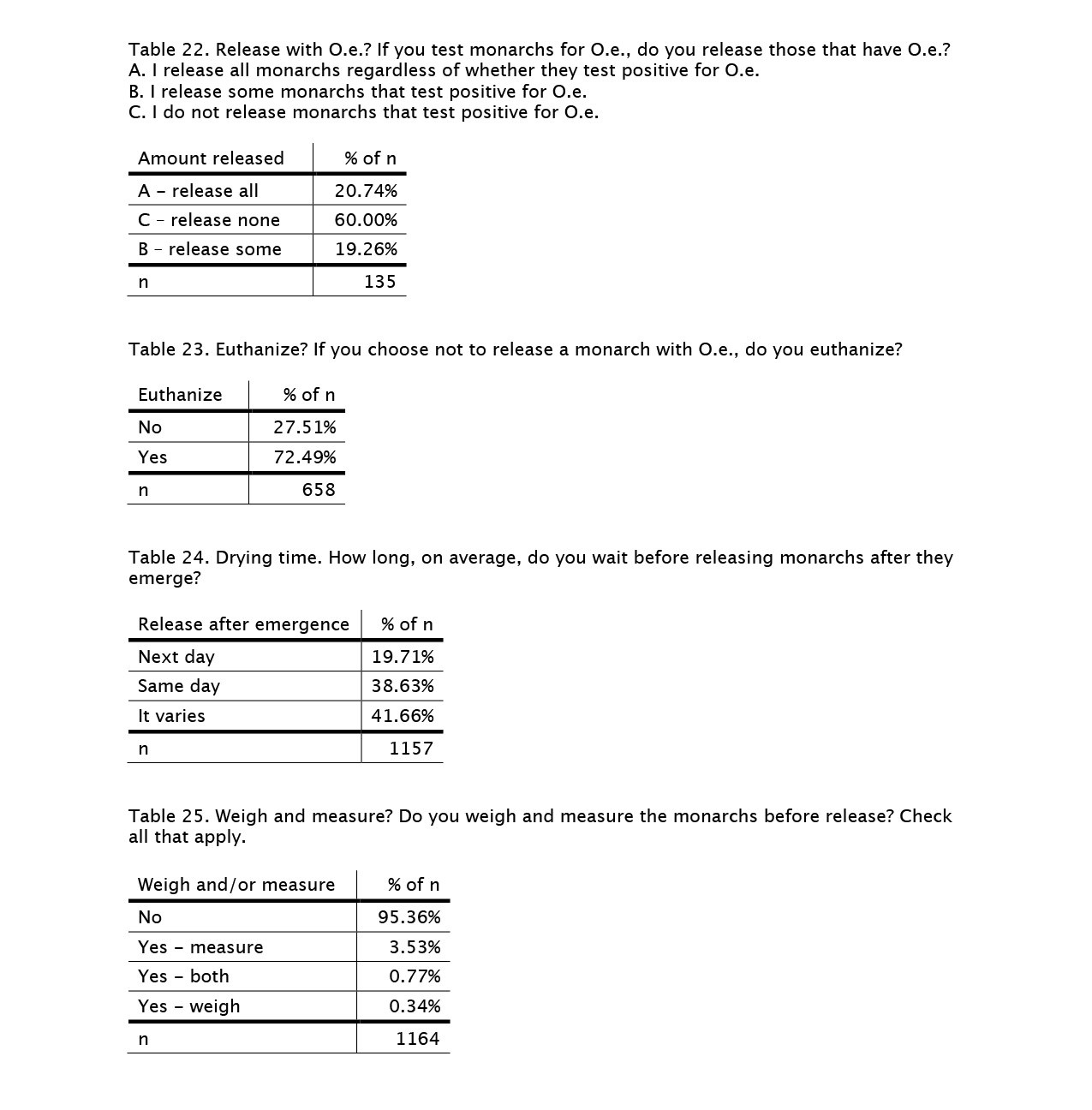

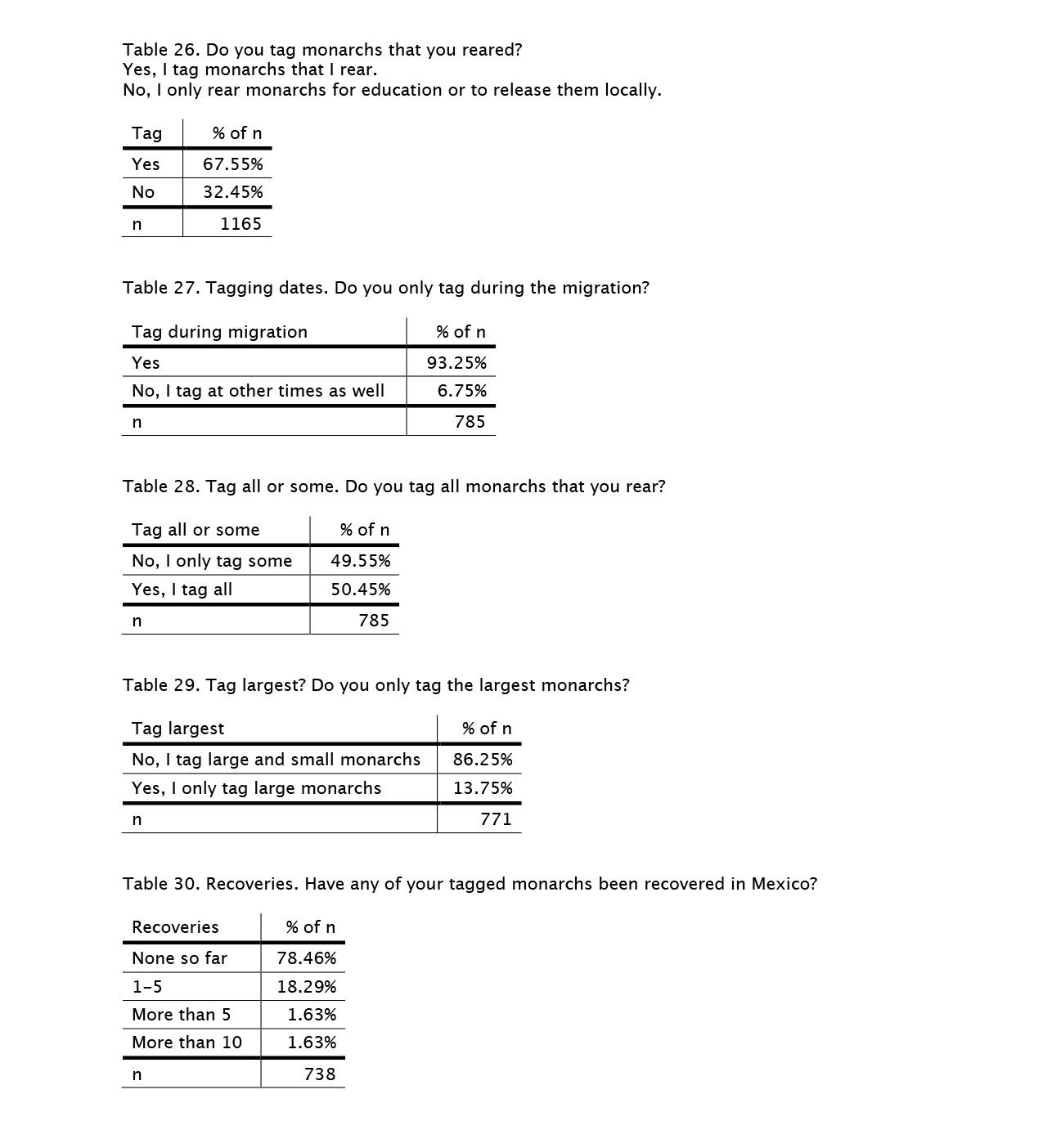

In the middle of Covid-19 last June, we conducted a survey of those who rear, tag and release monarchs. Life has been interrupted in many ways over the past year, and we are just now getting around to summarizing the responses (see link below). The number of people who responded (N=1165) exceeded our expectations, and their responses probably represent a good sampling of the reasons people engage in rearing and their rearing practices. Thank you to everyone who participated in our survey!

Monarch rearing, tagging and releasing survey

https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2021/07/06/monarch-rearing-tagging-and-releasing-survey/

——————————————————

10. About This Monarch Watch List

——————————————————

Monarch Watch (https://monarchwatch.org) is a nonprofit education, conservation, and research program affiliated with the Kansas Biological Survey & Center for Ecological Research at the University of Kansas. The program strives to provide the public with information about the biology of monarch butterflies, their spectacular migration, and how to use monarchs to further science education in primary and secondary schools. Monarch Watch engages in research on monarch migration biology and monarch population dynamics to better understand how to conserve the monarch migration and also promotes the protection of monarch habitats throughout North America.

We rely on private contributions to support the program and we need your help! Please consider making a tax-deductible donation. Complete details are available at https://monarchwatch.org/donate or you can simply call 785-832-7374 (KU Endowment Association) for more information about giving to Monarch Watch.

If you have any questions about this email or any of our programs, please feel free to contact us anytime.

Thank you for your continued interest and support!

Jim Lovett

Monarch Watch

https://monarchwatch.org

You are receiving this mail because you were subscribed to the Monarch Watch list via monarchwatch.org or shop.monarchwatch.org – if you would rather not receive these periodic email updates from Monarch Watch (or would like to remove an old email address) you may UNSUBSCRIBE via https://monarchwatch.org/unsubscribe

If you would like to receive periodic email updates from Monarch Watch, you may SUBSCRIBE via https://monarchwatch.org/subscribe

This e-mail may be reproduced, printed, or otherwise redistributed as long as it is provided in full and without any modification. Requests to do otherwise must be approved in writing by Monarch Watch.

Filed under Email Updates | Comments Off on Monarch Watch Update July 2021