28 July 2022 | Author: Jim Lovett

This newsletter was recently sent via email to those who subscribe to our email updates. If you would like to receive periodic email updates from Monarch Watch, please take a moment to complete and submit the short form at monarchwatch.org/subscribe/

Greetings, Monarch Watchers.

It is with heavy hearts that we start this month’s communication by sharing this tragic news with the Monarch Watch community:

Three family members, formerly of Lawrence, killed in ‘senseless’ shooting in Iowa

https://lawrencekstimes.com/2022/07/23/schmidt-family-killed-iowa-shooting

Sarah worked for Monarch Watch in the early 2000s and she and Tyler both contributed greatly to Monarch Watch’s development and continuation. We are absolutely shocked by this horrific act of violence. Our thoughts are with all of Sarah’s family members as they try to move forward during this unimaginably difficult time. A GoFundMe campaign has been set up for her 9-year-old son who survived the attack.

Included in this issue:

1. Monarch Population Status

2. Monarch Watch Tagging Kits for 2022

3. Submitting Tag Data

4. Tagging Wild and Reared Monarchs

5. Monarch Waystations

6. Monarch Calendar Project

7. Upcoming Monarch Watch Events

8. IUCN Red Listing of Monarchs

9. About This Monarch Watch List

——————————————————

1. Monarch Population Status

——————————————————

Each year at this time I summarize what I know about how the monarch population is developing. The idea is to give taggers a heads-up about what to expect during the migration. The trouble with this exercise is that the available data are often contradictory (like this year) and there never seem to be a sufficient number of observations. Also, there is often a lull in monarch activity in early July which can be misleading and critical weather information, particularly temperature summaries, needed to assess population growth can also be lagging. Ok, that sums up my excuses. Here is what I do know, based on first sightings reported to Journey North and temperatures from 8 Tempest weather stations scattered from eastern North Dakota to central Ohio.

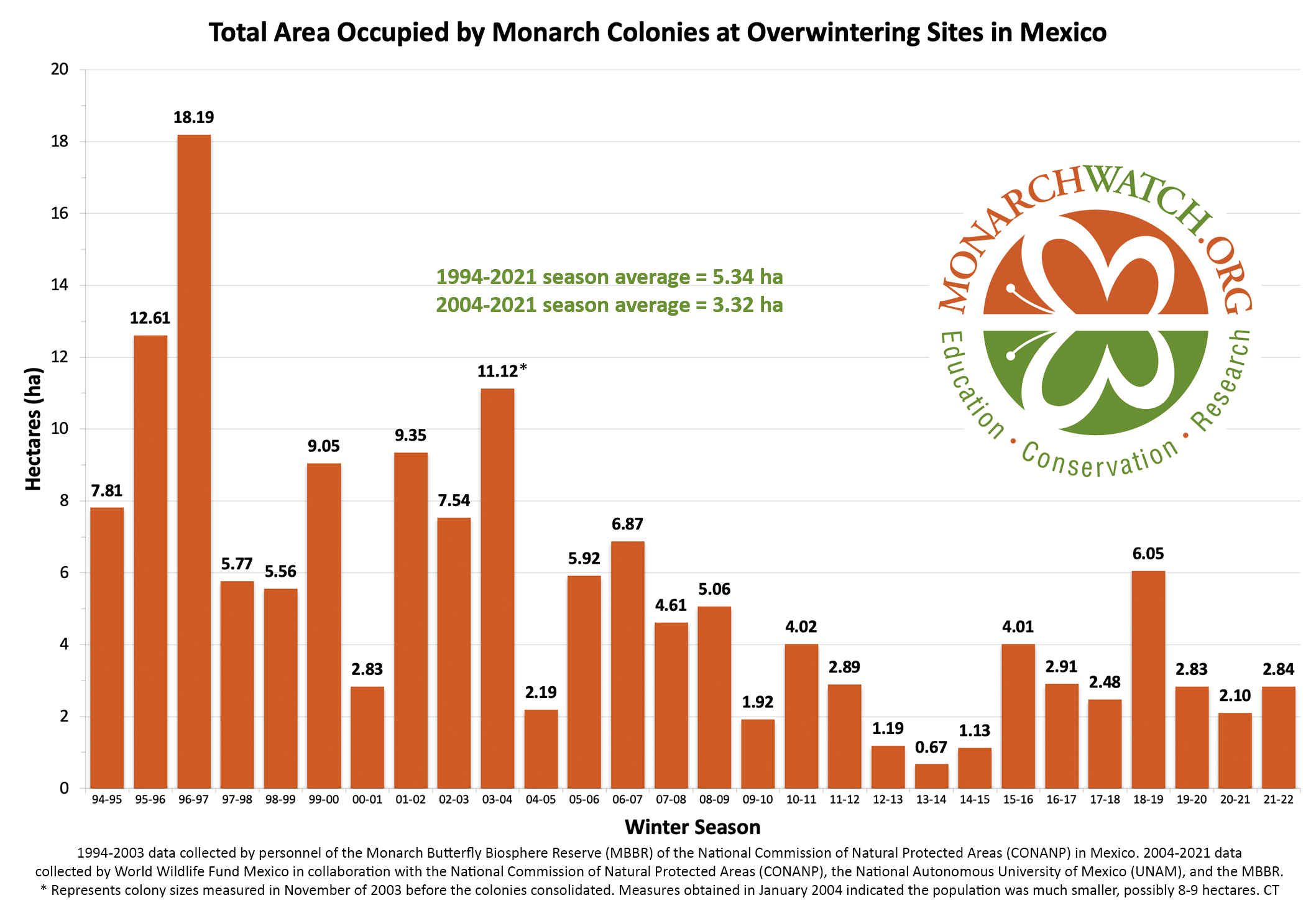

The monarchs returning from the overwintering sites in Mexico arrived in Texas in noticeable numbers between 11-15 March which fits with the long-term pattern of arrivals. The numbers reported were somewhat lower than last year but average for the last 5 years. I was a bit concerned about the returning numbers at the time, but the overall timing and numbers reported suggested the population was off to a fairly good start.

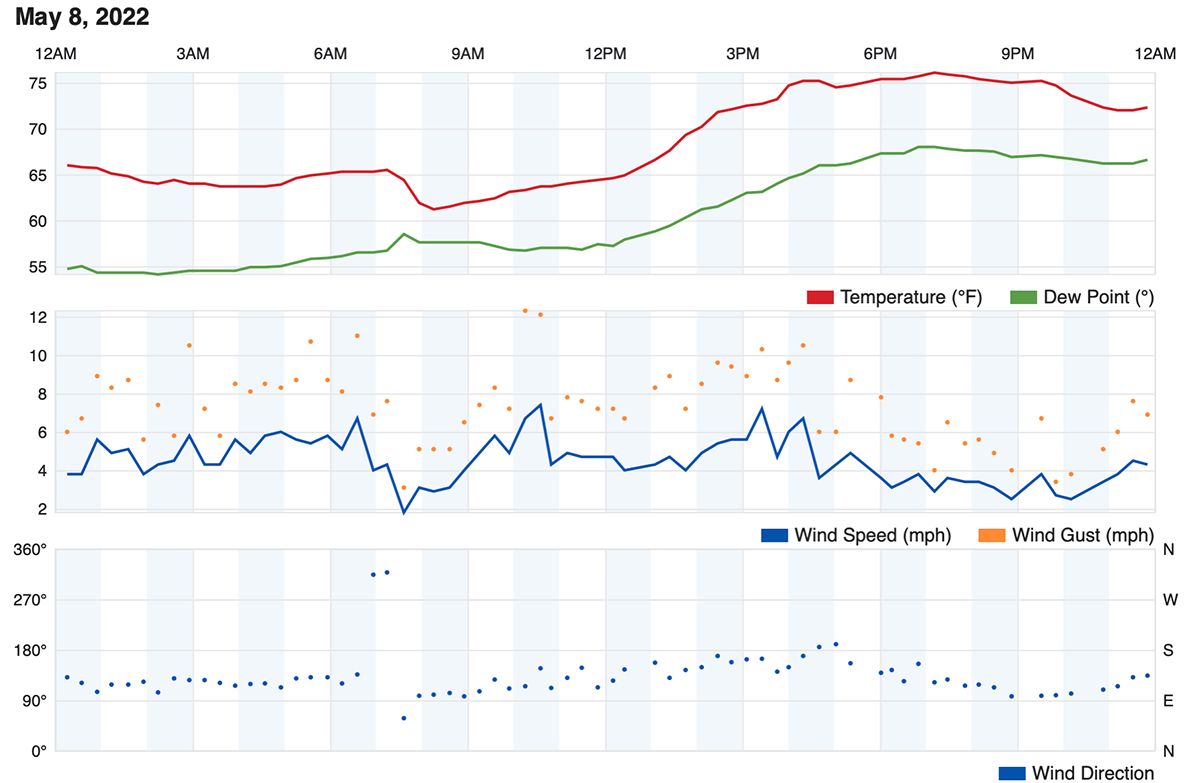

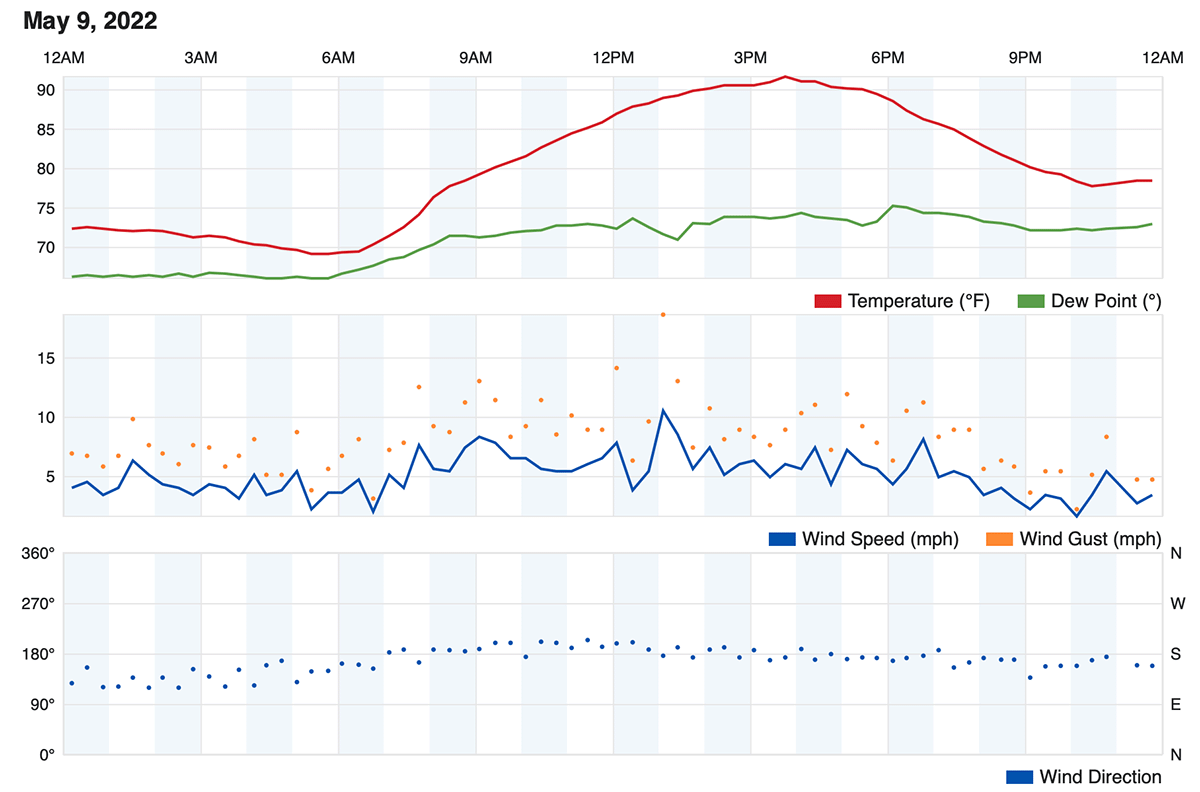

I next focused on the timing and number of first-generation monarchs moving north out of Texas in May. The first two weeks of May can be a low period for first sightings, but there was a surge of these in the central part of the Midwest from about 10-20 May. That was something to cheer about since that push northward, aided by strong SW winds, was a sign that the population in the Upper Midwest would be off to an early start. But that was not to be. A week of cooler, less favorable, weather followed in many areas. In fact, there were large areas in the eastern Midwest where the cooler weather lasted for three weeks, substantially slowing population development. Added to these conditions, the total number of first sightings in the Upper Midwest was the lowest since 2019 and strikingly low for the area from Madison, WI to the central Dakotas (90-100W longitudes). It is this region that is best represented by tag recoveries in Mexico. Together, delayed development and lower-than-average numbers suggest that the migration in the Midwest will be lower than average in late August and September. It will also be later, which will enable taggers to in many areas to tag monarchs well into September in the north and October in the south.

While the peak colonization of the area from the mid Dakotas (100W) to western Pennsylvania (80W) occurred from 11-20 May, colonization to the east (80-60W) peaked from 21-30 May. The difference in timing between the Midwest and East was unlike any record in the past for May. In addition, the numbers reported in the east were the highest in the 22-year record. These reports amounted to 38% of all sightings. The numbers included 30 sightings in the Maritime provinces – almost double the previous high (17) for that region. The record of colonization in the east may or may not signal a larger than average migration in the east; it is simply too early to tell. But, like the Midwest, it seems likely that the migration will be late and offer an opportunity for tagging well into September and early October along the eastern monarch flyways.

——————————————————

2. Monarch Watch Tagging Kits for 2022

——————————————————

Monarch tagging continues to be an important tool to help us understand the monarch migration and annual cycle – a long-term record is crucial to understand the dynamics of such complex natural phenomena. Tags for the 2022 fall tagging season are available and we have started shipping preorders out this week, ahead of the migration in your area. If you would like to tag monarchs this year, please order your tags soon! Tagging Kits ordered now should arrive within 10–14 days but priority will be given to preorders and areas that will experience the migration first.

Monarch Watch Tagging Kits are only shipped to areas east of the Rocky Mountains. Each tagging kit includes a set of specially manufactured monarch butterfly tags (you specify quantity), a data sheet, tagging instructions, and additional monarch / migration information. Tagging Kits for the 2022 season start at only $15 and include your choice of 25, 50, 100, 200, or 500 tags.

Monarch Watch Tagging Kits and other materials (don’t forget a net!) are available via the Monarch Watch Shop online at shop.monarchwatch.org – where each purchase helps support Monarch Watch.

2022 datasheets and instructions are available online via the Monarch Tagging Program page at monarchwatch.org/tagging

Tagging should begin in early to mid-August north of 45N latitude (e.g. Minneapolis), late August at other locations north of 35N (e.g., Oklahoma City, Fort Smith, Memphis, Charlotte) and in September and early October in areas south of 35N latitude. See a map and tables with expected peak migration dates and suggested dates to begin tagging on the Monarch Tagging Program page at the link above.

——————————————————

3. Submitting Tag Data

——————————————————

Thousands of you have submitted your 2021 season tag data to us by mail or via our online submission form – thank you! We are still receiving data sheets and if you haven’t submitted your data yet (for 2021 or even previous years) it is not too late. Please review the “Submitting Your Tagging Data” information on the tagging program page then send us your data via the Tagging Data Submission Form.

Complete information is available at monarchwatch.org/tagging if you have questions about submitting your data to us and we have conveniently placed a large “Submit Your Tagging Data” button on our homepage at monarchwatch.org that will take you directly to the online form.

There you can upload your data sheets as an Excel or other spreadsheet file (PREFERRED; download a template file from monarchwatch.org/tagging) or a PDF/image file (scan or photo).

If you have any questions about getting your data to us, please feel free to drop Jim a line anytime via JLOVETT@KU.EDU

Coming Soon: we plan to have the Monarch Watch mobile app available in the App Store (Apple iOS) and Google Play (Android) in August which will allow you to record and submit your tag data, report recoveries of tagged monarchs, participate in the Monarch Calendar program, and more! We will announce the app via social media and you can keep checking our site for updates at monarchwatch.org/app

——————————————————

4. Tagging Wild and Reared Monarchs

——————————————————

As a reminder, the following is an abbreviated version of our “Tagging wild and reared monarchs: Best practices” article posted to our Blog in 2019. The complete text of the article is available via the link below.

Diving into the tagging data has revealed a number of surprises such as the difference between the probability that a reared monarch will reach Mexico and the probability that a wild–tagged monarch will do so. The recovery rate is higher for wild–caught monarchs (0.9% vs 0.5%) and it is the data from the wild–caught butterflies that tell us the most about the migration. Frankly, for some analyses, we have to set the reared monarch data aside. That doesn’t mean it is not valuable, but its uses are limited.

It should be noted that for tagging data purposes, monarchs captured as adult butterflies should be reported as WILD and adult monarchs reared from the egg, larva, or pupa stage should be considered REARED.

TAGGING WILD-CAUGHT MONARCHS

For wild-caught monarchs we need to:

1. increase the number of taggers from western Minnesota and Iowa westward into Nebraska and the Dakotas to give us a more complete understanding of dynamics of the migration;

2. increase the number of wild monarchs that are tagged since these provide the most valuable data; and

3. increase the number of taggers who tag from the beginning of the tagging season in early August until the migration ends. Tagging records for the entire season will help us establish the proportion of the late–season monarchs that reach the overwintering sites. When tagging wild–caught monarchs, many taggers run out of tags well before the season ends. That’s great, but it would help us to know when all tags had been used by indicating this via the online tagging data submission form.

TAGGING REARED MONARCHS

Reared butterflies tend to average smaller than wild migrants. That difference can be reduced significantly if careful attention is given to rearing larvae under the best possible conditions. Large monarchs have the best chance of reaching Mexico, surviving the winter and reproducing in Texas. There are several reasons for this: better glide ratio, better lift with cross or quartering winds, larger fat bodies, more resistance to stress, etc. There are very few small monarchs among those that return in the spring. For those of you who prefer to rear, tag and release, we have a few suggestions:

1. Rear larvae under the most natural conditions possible.

2. Provide an abundance of living or fresh-picked and sanitized foliage to larvae.

3. Provide clean rearing conditions.

4. Plan the rearing so that the newly-emerged monarchs can be tagged early in the migratory season (10 days before to 10 days after the expected date of arrival of the leading edge of the migration in your area).

5. Tag the butterflies once the wings have hardened and release them the day after emergence if possible.

6. When it comes to tagging, tag only the largest and most-fit monarchs (see complete article for some guidelines). Records of tags applied to monarchs that have little chance of reaching Mexico add to the mass of tagging data, but do not help us learn which monarchs reach Mexico – unless the measurements, weight and condition of every monarch tagged and released is recorded. There are a few taggers who keep such detailed records and those data can be very informative. If you collect such data and are willing to share it please contact us; do not add this information to the standard tagging data sheet.

As a final note, this text is not a directive. We are not telling you what to do; rather, we are simply providing suggestions that may lead to more successful rearing and tagging efforts. The expanded version of this article is available at

Tagging wild and reared monarchs: Best practices – monarchwatch.org/blog/tagging-best-practices

——————————————————

5. Monarch Waystations

——————————————————

To offset the loss of milkweeds and nectar sources we need to create, conserve, and protect monarch butterfly habitats. You can help by creating “Monarch Waystations” in home gardens, at schools, businesses, parks, zoos, nature centers, along roadsides, and on other unused plots of land. Creating a Monarch Waystation can be as simple as adding milkweeds and nectar sources to existing gardens or maintaining natural habitats with milkweeds. No effort is too small to have a positive impact.

Have you created a habitat for monarchs and other wildlife? If so, help support our conservation efforts by registering your habitat as an official Monarch Waystation today!

monarchwatch.org/waystations

A quick online application will register your site and your habitat will be added to the online registry. You will receive a certificate bearing your name and your habitat’s ID that can be used to look up its record. You may also choose to purchase a metal sign to display in your habitat to encourage others to get involved in monarch conservation.

As of 5 July 2022, there have been 39,570 Monarch Waystation habitats registered with Monarch Watch! Texas holds the #1 spot with 3,338 habitats and Illinois (3,046), Michigan (2,901), California (2,516), Ohio (2,073), Florida (2,010), Virginia (1,754), Wisconsin (1,712), Pennsylvania (1,705) and Ontario (1,281) round out the top ten.

You can view the complete listing and a map of approximate locations via monarchwatch.org/waystations/registry

——————————————————

6. Monarch Calendar Project

——————————————————

For those of you participating in our Monarch Calendar project for 2022 (complete details and short registration form at monarchwatch.org/calendar), observation Period 1 has ended (the final date being June 20th, for those of you north of 35N). Once you have logged all of your observations using whatever format works for you (spreadsheet, notebook, calendar, etc.), please use the appropriate online form to submit your data to us:

2022 Period 1 Submission Forms:

—————————————-

SOUTH (latitude less than 35N)

—————————————-

Form for Period 1 (15 March – 30 April): forms.gle/fp7P1QM38CyCWWWa8

—————————————-

NORTH (latitude greater than 35N)

—————————————-

Form for Period 1 (1 April – 20 June): forms.gle/7FfUaywratxLbG7u5

The second observation period runs from 15 July–20 August in the North and 1 August–25 September in the South. As soon as the fall period ends for all locations we will send out links for submission of that data to all who have registered.

Again, complete details and a link to the short registration form are available at monarchwatch.org/calendar

——————————————————

7. Upcoming Monarch Watch Events

——————————————————

Monarch Watch Tagging Event (Free event)

Saturday, September 17, 2022

Baker Wetlands Discovery Center

Lawrence, Kansas

monarchwatch.org/tag-event

We have other events we are planning for the fall and will announce soon. Stay tuned!

——————————————————

8. IUCN Red Listing of Monarchs

——————————————————

The recent news about the IUCN’s Red List does not change the status of monarchs in the U.S.

In a December 15, 2020 press release, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced its decision with respect to the petition to declare the monarch a “threatened” species under the Endangered Species Act:

“After a thorough assessment of the monarch butterfly’s status, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) has found that adding the monarch butterfly to the list of threatened and endangered species is warranted but precluded by work on higher-priority listing actions. With this decision, the monarch becomes a candidate for listing under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), and its status will be reviewed each year until it is no longer a candidate.”

Upon that announcement, we wrote that the “warranted but precluded” decision for monarchs is the right one at this time. It acknowledges the need for continued vigilance due to the numerous threats to the population while emphasizing the need to continue support for programs that create and sustain habitats for monarchs. It also should be clear that it is the North American monarch migration that is threatened and not the species, which is widely distributed in the Americas and elsewhere.

Please see our full response to this posted via our blog in 2020 at monarchwatch.org/blog/2020/12/15/esa-listing-decision-for-the-monarch/

Thank you for your interest and concern!

——————————————————

9. About This Monarch Watch List

——————————————————

Monarch Watch ( https://monarchwatch.org ) is a nonprofit education, conservation, and research program affiliated with the Kansas Biological Survey & Center for Ecological Research at the University of Kansas. The program strives to provide the public with information about the biology of monarch butterflies, their spectacular migration, and how to use monarchs to further science education in primary and secondary schools. Monarch Watch engages in research on monarch migration biology and monarch population dynamics to better understand how to conserve the monarch migration and also promotes the protection of monarch habitats throughout North America.

We rely on private contributions to support the program and we need your help! Please consider making a tax-deductible donation. Complete details are available at https://monarchwatch.org/donate or you can simply call 785-832-7374 (KU Endowment Association) for more information about giving to Monarch Watch.

If you have any questions about this email or any of our programs, please feel free to contact us anytime.

Thank you for your continued interest and support!

Jim Lovett

Monarch Watch

https://monarchwatch.org

You are receiving this mail because you were subscribed to the Monarch Watch list via monarchwatch.org or shop.monarchwatch.org – if you would rather not receive these periodic email updates from Monarch Watch (or would like to remove an old email address) you may UNSUBSCRIBE via https://monarchwatch.org/unsubscribe

If you would like to receive periodic email updates from Monarch Watch, you may SUBSCRIBE via https://monarchwatch.org/subscribe

This e-mail may be reproduced, printed, or otherwise redistributed as long as it is provided in full and without any modification. Requests to do otherwise must be approved in writing by Monarch Watch.

Filed under Email Updates | Comments Off on Monarch Watch Update July 2022

We are always looking for monarch photos, videos, stories and more for use on our website, on our social media accounts, in our publications, and as a part of other promotional and educational items we distribute online and offline to promote monarch conservation and Monarch Watch.

We are always looking for monarch photos, videos, stories and more for use on our website, on our social media accounts, in our publications, and as a part of other promotional and educational items we distribute online and offline to promote monarch conservation and Monarch Watch.