18 July 2008 | Author: Chip Taylor

“Where are the monarchs?” has been a common question asked of us over the last month or so and the following is the best answer I can provide at this time.

“Where are the monarchs?” has been a common question asked of us over the last month or so and the following is the best answer I can provide at this time.

Thanks to all of you who have contacted us with your assessments of the status of the monarch population. The vast majority of reports indicate that the monarch population appears to be much lower than normal. Most of these observations have been from areas where the monarchs are between broods and sightings of adults are usually low in early and mid July. So, this aspect of the reports is not alarming. The general absence (or low numbers) of larvae, as indicated in many reports, is of greater concern. The larvae present now mature into adults in late July and early August. These butterflies produce the offspring (from eggs generally laid from the 20th of July to the 10th of August) that become the butterflies that join the fall migration. Again, with few exceptions, unless you are all missing something out there, the number of reproducing adults over the next three weeks will be low, to be followed by a relatively small migratory generation. This assessment could be wrong of course and let’s hope that this is the case.

Assuming our collective assessments are, in fact, correct and that the population is low, how do we account for the lower than expected number of monarchs?

Here is what I know about the monarch population (December 2007 to the present):

1. The overwintering population in Mexico measured 4.61 hectares, a bit lower than the average of about 6 hectares in recent years, but not alarmingly so.

2. Although mortality during the winter was higher than normal at one location on Cerro Pelon, overwintering mortality appeared to be normal at other locations.

3. Examination of monarchs at several colonies at the end of the season showed them to be in remarkable condition with large numbers of nearly immaculate butterflies with large fat bodies. The proportion of monarchs in poor condition appeared to be lower than normal.

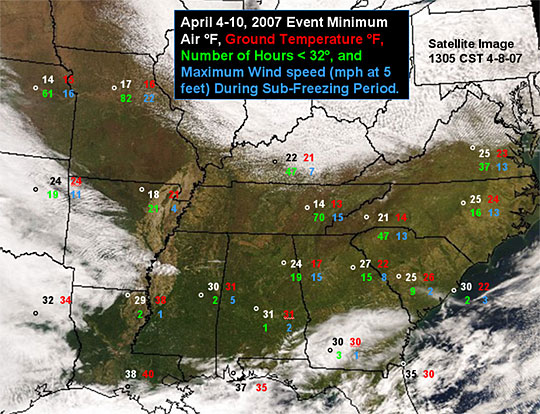

4. The migration into Texas appeared to be quite good, although a bit delayed. Some monarchs lingered at the overwintering sites as late as the first week of April. Various observers in Texas reported large numbers of returning adults and others subsequently reported large numbers of larvae on milkweeds in pastures south of Dallas.

5. March temperatures in Texas were neither too hot nor too cold and the simple temperature based model I’m developing suggested at that time that the overwintering population might be as high as 8 hectares. All appeared to be well in Texas and on track to produce a large number of first generation monarchs that could colonize the northern breeding grounds.

6. The first generation monarchs usually pass through Kansas from the last few days of April through the first week of June. During good years, the movement of first generation monarchs through this area can be quite conspicuous with many of the passing monarchs stopping to lay eggs on the blooming milkweeds. There was no obvious “flow” of first generation monarchs through the area this year and relatively few eggs and larvae were found on milkweeds in May and early June.

7. This observation gives rise to two questions: a) was the first generation much smaller than expected? and b) are there other explanations for the relatively low numbers of monarchs that reached the northern breeding grounds? Or, is the explanation some composite of these two possibilities?

8. At this point there is no way to assess the success of the first generation in Texas and other southern states. If the fire ant population was higher than it has been in recent years, predation by these ants could have had an impact. However, I don’t think the ants are widespread or abundant enough to have a large-scale impact on the population. The weather during March and early April in Texas was favorable for reproduction so I’m inclined to look to another cause.

9. May, the moving month for first generation monarchs, was cold – throughout the entire northern breeding range. It was also a period of frequent storms and heavy rains, particularly during the second half of May. Early June also saw heavy rains, especially in the east north central and central portions of the country.

10. In spite of these limiting conditions, bursts of monarchs reached some northern breeding areas, notably Iowa, parts of Ontario, and southern New England.

11. So, how could the May and early June conditions have limited the monarchs? In a few words, by: a) limiting dispersal, b) reducing egg laying, and c) increasing mortality of adults. All together such effects result in a reduction of the potential fecundity of the generation and the “realized fecundity” is lower than expected. The impact of lower temperatures and heavy rains on survival of larvae are unknown but might also have reduced the population.

12. What about the future? The monarchs could surprise us. If temperatures are moderate for the remainder of the summer and a substantial number of eggs are laid from 20 July to 10 August, the population could rebound.

13. As a number of you have pointed out, this year is not a good year for butterflies in general. This means that the parasites and predators that make a living feeding on a broad range of lepidopterous larvae are starving or not reproducing in good numbers. If parasites and predators are low, the result could be that there will be a reduction in the loss of monarch larvae during the last generation giving rise to a larger migratory population that seems to be indicated at this time.

Based on what we know now, my expectation is that the overwintering population in Mexico will be lower than the 4.61 hectares measured last year. As always, I hope my predictions are overly pessimistic.

Filed under Monarch Population Status | 45 Comments »

The 2008 monarch tagging season is upon us!

The 2008 monarch tagging season is upon us! “Where are the monarchs?” has been a common question asked of us over the last month or so and the following is the best answer I can provide at this time.

“Where are the monarchs?” has been a common question asked of us over the last month or so and the following is the best answer I can provide at this time.

Predicting the number of monarch tags recovered in Mexico each winter is a bit of a guessing game. If we hear of a winter storm causing a lot of mortality at the colonies, we can anticipate that many tags will be available. Following mild winters the number of tags recovered might be as low as 150 from the tens of thousands of monarch butterflies tagged the previous fall. This winter was quite mild, perhaps even a bit on the warm side, and there was only one report hinting at higher than normal rates of mortality. So, we headed for Mexico expecting to acquire roughly 300 tags but were prepared to pay for up to 600 should this many be available. To our surprise, there were over 600 tags available. In fact, if we had had the funds, we could have purchased 200 more. Adding those purchased to those donated to Monarch Watch by various visitors to the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve (MBBR) brings the total number of tags recovered in Mexico this season to about 670.

Predicting the number of monarch tags recovered in Mexico each winter is a bit of a guessing game. If we hear of a winter storm causing a lot of mortality at the colonies, we can anticipate that many tags will be available. Following mild winters the number of tags recovered might be as low as 150 from the tens of thousands of monarch butterflies tagged the previous fall. This winter was quite mild, perhaps even a bit on the warm side, and there was only one report hinting at higher than normal rates of mortality. So, we headed for Mexico expecting to acquire roughly 300 tags but were prepared to pay for up to 600 should this many be available. To our surprise, there were over 600 tags available. In fact, if we had had the funds, we could have purchased 200 more. Adding those purchased to those donated to Monarch Watch by various visitors to the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve (MBBR) brings the total number of tags recovered in Mexico this season to about 670.