28 January 2015 | Author: Chip Taylor

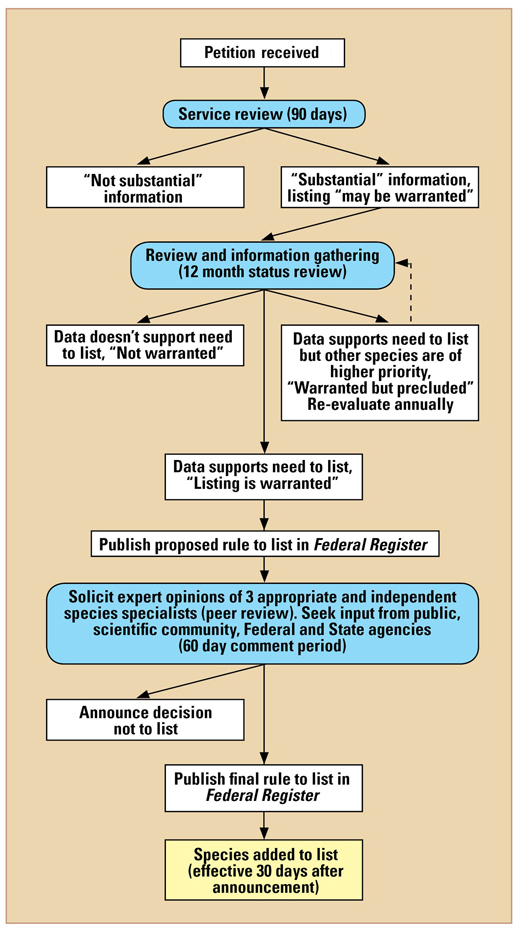

In an earlier posting to this blog I commented on the “Petition to protect the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus plexippus) under the Endangered Species Act” (see Commentary: Recent Petition to Protect the Monarch Butterfly). The commentary included notes about the petition, the distinction between endangered and threatened (a distinction frequently ignored by the press), and the process a petition goes through from the time of submission to acceptance or rejection. I briefly touched on outcomes and finished with some thoughts on the urgent need for restoration. From these comments, it should have been clear that I do not endorse the petition. I avoided providing an explanation for my opposition but, given recent commentary on discussion lists and superficial coverage in the press, in which the reporters consistently fail to ask the hard questions, I have decided to come forth with some thoughts on the petition and to suggest an alternative to the for/against positions that dominate current discourse on this issue.

OUR CHOICES

Our choices are based on the following three premises:

1) Monarchs are not threatened.

2) Monarchs are threatened.

3) Monarchs have declined due to habitat loss requiring large-scale funding of public-private partnerships (P3) to restore enough habitat to sustain the migration.

The potential outcomes associated with each premise are as follows.

1) Premise: Monarchs are not threatened.

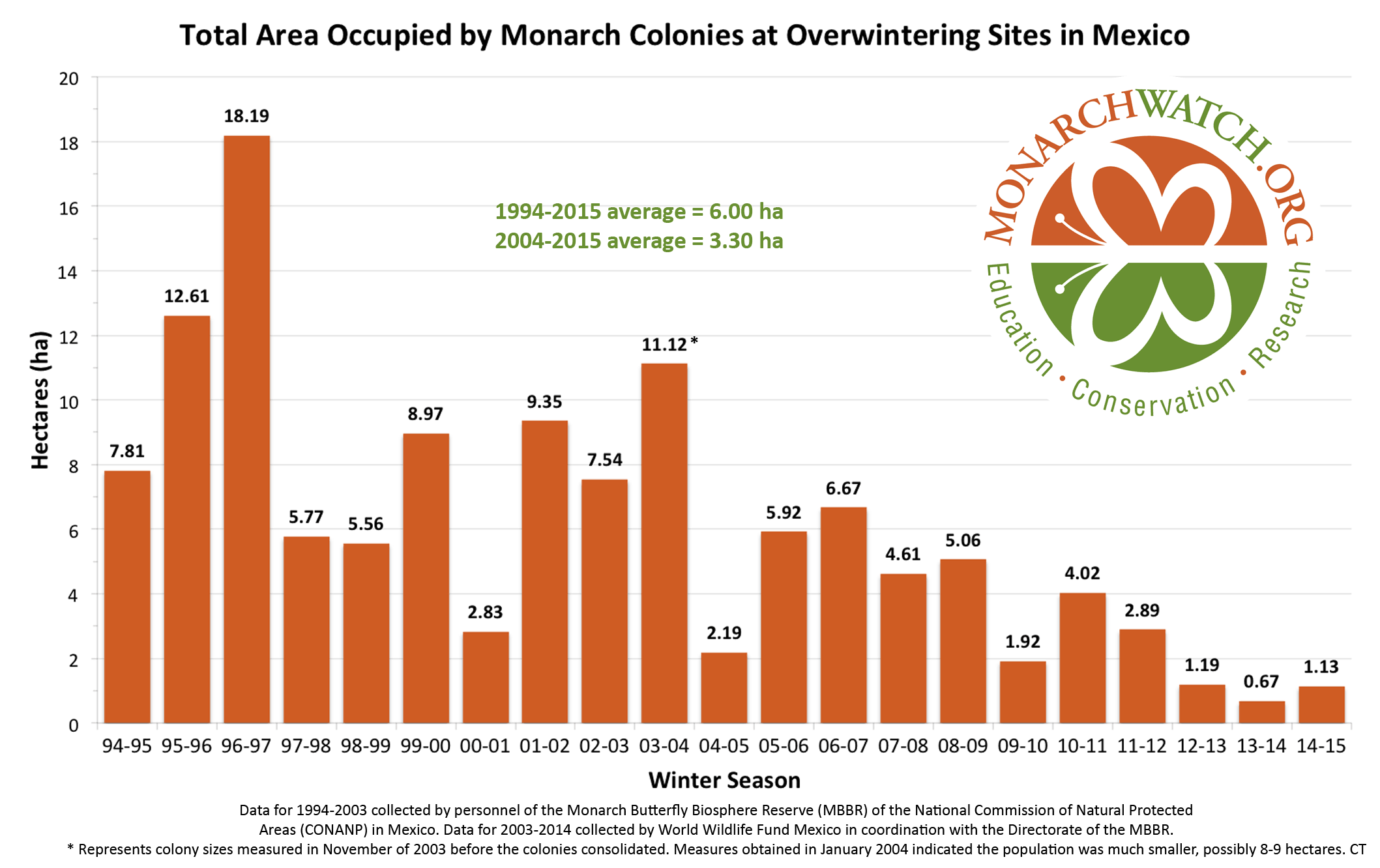

We can argue that threatened status is not needed since there is enough milkweed left in the upper Midwest to produce an overwintering population of 3-4 hectares (Pleasants, pers. com.). We can also argue that the rebound in the population this year (from 33.5 million in 2014 to 56.5 million in 2015), indicates that threatened status and regulation are not needed at this time.

This position fails to recognize that milkweed/monarch habitat is declining at a rate of at least a million acres a year within the core breeding areas from Texas through the Upper Midwest (see Monarch Butterfly Recovery Plan).

Outcomes:

A) Monarchs will continue to decline

B) The public will eventually lose interest in monarchs (out of sight out of mind) and the migration will become a memory.

2) Premise: Monarchs are threatened.

Plan A: Threatened status implements standard rules and regulations.

We can argue that the evidence summarized in the petition justifies classification of the monarch butterfly as a threatened species. If the evidence is sufficient and the premise is accepted, threatened status will come with lots of rules, regulations and interpretations. There are rules and regulations that apply to critical habitat on public and private lands and regulations that restrict the public’s access to the species or habitats in question. Many are asking the questions, “How will monarchs actually be protected by such a ruling? What will be the impact on landowners, citizen science programs, backyard rearing programs, collecting, commercial breeding and distribution of monarchs? (See definition of “taking” in footnote.) Will the federal government have the personnel and funds (100s of millions of dollars) to enforce restrictions and administer a habitat program that covers much of the United States?” Threatened status for the monarch will have consequences and these need to be carefully considered. It is important for all concerned to be aware of the impact threatened status might have on their relationship with monarchs.

Outcomes:

A) Habitat protection and restoration will occur on both public and private lands and (i) lead to an increase in monarch numbers and a sustained migration or (ii) the scale of such efforts will be insufficient to protect the monarch migration

B) Milkweeds will be eradicated en masse on private lands before implementation of rules governing protection of milkweeds

C) Public interest in monarchs will decline following regulations restricting access to this species

D) Perceptions that the government will solve the “monarch problem” will diminish the public’s interest in creating habitats for monarchs

E) Constraints, particularly funding and personnel, will limit the prospect of saving the monarch migration

Plan B: Threatened status does not regulate critical habitat on private lands yet implements restoration partnerships with landowners.

Again, the presumption is that monarchs are threatened. In this case however, in recognition of the enormous task of tracking and monitoring milkweed/monarch habitats on private lands, and limited financial resources, attempts to protect critical milkweed habitats will be limited to public lands. Restoration of milkweed/monarch habitats on private lands will be accomplished through partnerships with landowners. Rules and regulations restricting public access to monarchs would still be implemented. Adoption of this approach also raises questions because the ability to form partnerships to restore habitat is likely to be constrained by various capacity issues such as funding and personnel.

Outcomes:

A) Habitat protection and restoration by federal agencies will be implemented on public and private lands but will be limited by the ability to engage landowners in milkweed/monarch conservation. Given the lack of protection of critical habitats on private lands, the scale of such efforts would be less likely to protect the monarch migration

B) Public interest in monarchs will decline following regulations restricting access to this species

C) Constraints, particularly funding and personnel, will limit the prospect of saving the monarch migration.

3) Premise: Monarchs have declined due to habitat loss requiring large-scale funding of public-private partnerships (P3) to restore enough habitat to sustain the migration.

Implementing threatened status under the Endangered Species Act will hinder rather than assure survival of the monarch migration.

We can also argue, given that the monarch population is likely to continue declining in the coming years, the best way to restore milkweed/monarch habitats is through large-scale public-private partnerships (P3) – collaborative efforts rather than those driven by regulations. This approach emphasizes that what we need are programs that foster cooperation and restoration on both public and private lands. Implied in the premise is the notion that milkweed/monarch restoration needs to start immediately and that we can’t wait for a decision on the petition. The petition puts us in limbo since the earliest a decision would be made is in two years and a determination of its merits could be deferred for a number of years.

Outcomes:

A) Habitat protection and restoration will occur on both public and private lands and (i) lead to an increase in monarchs numbers and a sustained migration or (ii) the scale of such efforts will be insufficient to protect the monarch migration

B) Beginning this season, an emphasis on grass-roots and large-scale campaigns will engage the public and feed into and facilitate large-scale habitat restoration

C) These programs will increase the number of citizens and private entities engaged in monarch conservation and conservation in general

D) The scale of this approach is more likely to lead to a larger and more stable monarch population than either plan 2A or 2B above.

Reasons for supporting choice 3 (P3) vs. plan 2A include the following:

1) The magnitude of the task is enormous and will create financial, management and personnel issues for already underfunded and understaffed agencies charged with protecting monarchs.

2) Restoration of milkweed/monarch habitat will cost hundreds of millions of dollars. Funding a federal effort of this scale would require a substantial increase in the endangered species budget or reallocation of existing funds away from other endangered and threatened species endeavors to cover costs associated with monarch recovery. Given the present economy and political climate, it seems unlikely that congress will provide funds to cover the costs associated with milkweed/monarch restoration.

3) Landowners are very concerned about programs wherein government regulations dictate how they manage their lands. (Plan 2B would involve willing landowners, thus bypassing this concern).

4) Threatened status represents a governmental top-down approach to a conservation program and gives the impression that “protection” will be achieved by government actions alone.

5) Choice 3 is inclusive and recognizes that saving the monarch migration will require broad-based public (government) and private actions. This choice recognizes that monarch conservation is too big a task for either the public or private sector acting alone.

6) Collaboration is the only reasonable solution given the magnitude, cost and complexities associated with monarch conservation.

7) Choice 3 provides a better path for getting landowners and stakeholders to participate in monarch conservation. In particular, we need to engage the landowners (farmers and ranchers) and rural communities throughout the Upper Midwest (the source area for most monarchs that overwinter in Mexico) in monarch conservation. At the same time, we have to be sure that landowners in Texas maintain milkweeds that support the offspring of monarchs returning from Mexico each March and April.

8) There is uncertainty as to whether the petition will be acted on favorably in the near term or delayed for a decade or more. Monarchs can’t wait for this decision or implementation of an action plan such as plans 2A or 2B. We have to act now and we have to build the coalitions, partnerships, capacity, etc., to assure that the monarch migration continues. Large-scale restoration needs to begin this spring.

Although I favor Choice 3, the success of this approach, just as with 2A and 2B, would depend on the scale of the effort to protect and restore milkweed/monarch habitats. Sustaining the monarch migration will not be easy. Here is one example of a large-scale public-private partnership currently under development: USDA News Release – Farm Bill Initiative Marks New Era for Conservation efforts

Throughout this text I have focused on issues associated with restoration on public and private lands. Rules and regulations that limit access to monarchs are another concern but how these might be implemented is still an open question. Readers who are concerned about how such rules might affect them should read the petition carefully (Petition to protect the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus plexippus) under the Endangered Species Act) and should submit comments accordingly (via eRulemaking Docket ID: FWS-R3-ES-2014-0056). Depending on what rules and regulations are adopted from the petition, or perhaps new ones suggested by an advisory committee, it is possible that many activities associated with monarchs would be prohibited or severely limited. It is also possible that some of the restrictions suggested in the petition would not be adopted. Restrictions are usually adopted to “protect” a species and the number of individuals in the population but, truthfully, in this case, due to the size and distribution of the monarch population and its reproductive capacity, adoption of such restrictions will have little impact on the size of the migration or the overwintering population. This issue is all about scale and biology and the question is whether human activities such as backyard breeding, commercial activities, etc., are of sufficient scope and scale to impact an abundant and highly mobile species with a high reproductive rate. The decision makers should carefully consider the strength of the scientific evidence apart from the rhetoric on these issues.

The following are some of the questions that have concerned me about the petition. In addition to these questions, for which there are presently few answers, my preference for public-private partnerships, rather than threatened status, is based on participation in a number of high level meetings with scientists, experts from federal agencies, conversations with representatives of various NGOs and persons representing agricultural interests and industry. My sense is that monarch conservation is moving in the direction of public-private partnerships – irrespective of the petition requesting threatened status for the monarch.

Questions relevant to the petition

General questions

What is meant by the word “protection” in the context of protecting the monarch migration?

What would be protected and how would specific actions protect monarchs?

If the government is required by the Endangered Species Act to restore habitats for monarchs, what would be involved?

Assuming that the goal is to protect critical habitat, how do we define critical habitat?

Assuming we can identify and protect critical habitat on public lands, what would that mean for private lands?

How much land needs to be restored each year to compensate for the annual losses of milkweed/monarch habitats due to development, increase in crop acreage and other forms of land degradation? (Annual losses in the milkweed/monarch corridor are estimated to be at least a million acres per year – see Monarch Butterfly Recovery Plan).

How much land would have to be restored to bring the monarch back to a more stable population size – i.e., a population large enough to be able to survive catastrophic overwintering mortality and poor breeding seasons? Since most of these annual losses occur on private lands, how could threatened status be used to restore milkweeds to these or comparable sites? Who would monitor the habitat losses and who would follow up with appropriate remediation? How would this be coordinated and how would it be paid for?

How much does it cost to restore an acre of milkweed/monarch habitat? Depending on the method, costs of restoration and maintenance of milkweeds and nectar plants range from $100-$1000 per acre. If we need to compensate for the loss of a million acres per year in the milkweed/monarch corridor, the restoration alone could cost 100 million dollars per year and there would be additional millions associated with administrative costs as well. Who would cover those costs, especially if most of the restoration occurred on private lands? And, again, what sort of incentives and agreements would be needed between the government and landowners to accomplish this restoration? Further, do we have the capacity (e.g., seed stocks) for large-scale restoration and who would do it – federal, state or private restoration teams?

Going beyond the 1 million acres per year, how would the restoration of additional millions of acres be accomplished? And, how many millions are we talking about? Estimates are that 167 million acres of milkweed/monarch habitat have been lost since the introduction of GMO crops in 1997 and the signing of the ethanol mandate in late 2007. How much habitat needs to be restored to offset enough of this loss to create a population of sufficient size (4-5 hectare overwintering population) to be able to sustain losses due to extreme weather at the overwintering sites, or temperatures during March and April in the South Region (TX, OK and southern KS), or during extreme cold or warm summers in the Upper Midwest? Do we need to restore 5, 10 or 15 million acres? And, again, at what cost and who is going to do it and how much would involve public vs. private lands? Aside from capacity issues (seeds, manpower, equipment, etc.) would the federal government have the personnel, the infrastructure and the 100s of millions of dollars necessary to achieve the levels of restoration needed to sustain the monarch population?

Questions based on the assumption that plan 2A would be adopted

Would developers be blocked from developing due to the presence of milkweeds on properties they would like to develop? The rate of conversion of landscapes to development (housing, malls, industrial parks, etc.) is approximately 2 million acres per year – of which 1.24 million acres are rural lands (Farmland Information Center statistics).

If development involved displacement of milkweeds, would the developer be required to restore milkweeds in new areas? Who would coordinate these arrangements?

What types of incentives and agreements would be needed to get private land-owners to restore milkweeds and nectar plants to their properties?

How would existing milkweed stands on private lands be identified within the northern breeding area and throughout the milkweed/monarch corridor from Texas to the border with Canada. And, once identified, how would milkweed sites on private lands be protected? Would there be penalties for not properly maintaining milkweed patches on private land or purposefully destroying such patches?

Questions based on the assumption that plan 2B would be adopted

Plan 2B would be much like Choice 3 but would include various but, as yet undetermined, restrictions on the public’s access to monarchs. At issue here is the question about the size of the Federal effort. Would federal agencies have sufficient funds and personnel to cover a significant portion of the costs needed to restore the monarch population? This question takes us back to the magnitude of the effort needed to restore the monarch population. Habitat for monarchs is critically low. There is no excess habitat. The monarch population will continue to decline if we fail to recognize the annual rate of habitat loss (a million acres/year) and to offset these losses with restoration.

What’s the best plan for saving the monarch migration?

Which of the choices above gives us the best chance of saving the monarch migration? My money is on Choice 3 – public-private partnerships (P3). However, for this effort to be successful, we need a multitude of large-scale public-private partnerships that focus on the restoration of milkweed/monarch habitats from the Upper Midwest through central Texas. Further, we need to enhance monarch habitats throughout the United States.

There are many other questions and numerous long-term issues that neither the petition nor these comments address. That said, the most important question is – how can we slow down and even reverse the decline in monarch numbers? Given that we are losing at least a million acres of critical habitat a year, we can’t wait for a decision on the petition. We have to act NOW!

Definitions from the Endangered Species Act of 1973

The term “threatened species” means any species which is likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range.

The term “endangered species” means any species which is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range.

The term “take” means to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct.

(5)(A) The term “critical habitat” for a threatened or endangered species means—

(i) the specific areas within the geographical area occupied by the species, at the time it is listed in accordance with the provisions of section 4 of this Act, on which are found those physical or biological features (I) essential to the conservation of the species and (II) which may require special management considerations or protection; and

(ii) specific areas outside the geographical area occupied by the species at the time it is listed in accordance with the provisions of section 4 of this Act, upon a determination by the Secretary that such areas are essential for the conservation of the species.

(B) Critical habitat may be established for those species now listed as threatened or endangered species for which no critical habitat has heretofore been established as set forth in subparagraph (A) of this paragraph.

(C) Except in those circumstances determined by the Secretary, critical habitat shall not include the entire geographical area which can be occupied by the threatened or endangered species.

Filed under Monarch Conservation | Comments Off on Monarch Conservation: Our Choices