Monarch Population Status

17 November 2019 | Author: Chip TaylorWhy overwintering monarch numbers will be lower this year

I’ve had an answer in mind for weeks. It’s been dogging me. The question that’s the basis for this answer has many parts, and not all the parts have come together. It’s as if the answer is disconnected from the question. Some of you will remember Johnny Carson’s skits featuring “Carnac the Magnificent”. In the skit, Ed McMahon hands Carnac a succession of envelopes. Upon receiving each, Carnac holds the envelope to his forehead and announces an answer to the question sealed in the envelope. Carnac then tears open the envelope and reads a silly question that fits an off the wall answer. The absurdity of having an answer before knowing the question was great fun because life seldom works that way. When it comes to monarchs, the questions usually come first. In this case, my answer came first, and the task at hand is to determine if the many part question fits the answer, or not. And so it is with my attempts to predict the size of the overwintering population. It’s a process, part intuition and part data with an emphasis on the later. I’m sparing you the raw data in this account.

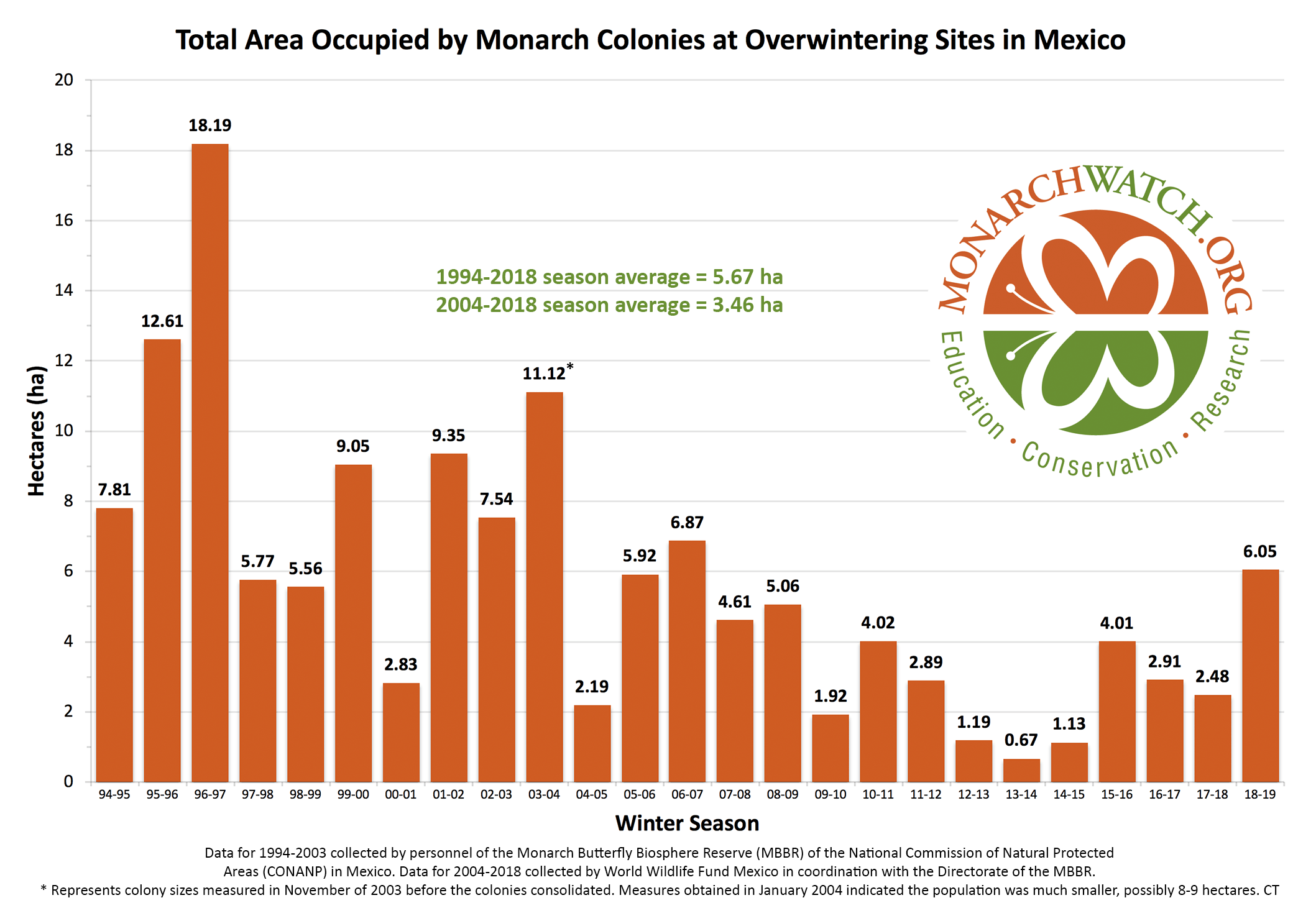

As I’ve mentioned in previous posts to this blog, I’m developing a stage-specific model that will allow me to predict the approximate size of the fall migration and the overwintering population. The model has 6 stages: 1) overwintering, 2) the return migration from the colonies to Texas, 3) reproduction by returning monarchs in March and April, 4) the migration north of the first generation in May and early June, 5) the growth of the population during the summer months and 6) the fall migration which I break up into three temporal/latitudinal segments. In addition, I consider regional monarch production, droughts, storms, and other weather events. Having put all of these measures and estimates together, I can tell you two things with certainty – I will be both right and wrong. I will be right about the size of the overwintering population relative to that of last year (6.05 hectares). The number this year will be lower. That’s been clear since late March and early April. I’ll explain why it will be lower below. The question I’ve been wrestling with is how much lower will the number be this winter. That’s where I’ll be wrong. I’ll never hit that number precisely. There are too many variables. The goal is to test the data and the assumptions with an estimate of the total area occupied by overwintering monarchs. The presumption is that, in time, as the model becomes more refined, the predictions will become more accurate. Similar models have been developed to predict salmon and waterfowl numbers.

To answer the question “How big will the overwintering population be this winter?” we need answers to many additional questions associated with the different stages and other factors. While not as large as last year, 4.7 is still a good number relative to the recent past. If I’m correct, 4.7 will be the second highest number of hectares since 2008. Although there is a lot of uncertainty in this estimate due to the lack of data on critical measures, it is likely that the area of trees occupied by monarchs will be between 4.3 and 5.3 hectares and will still be the second largest population since 2008. In the following text, I will provide a brief, somewhat sketchy, account of what has happened between the last migration and the one that is just finishing as monarchs continue to arrive at the overwintering sites.

Stages 1 & 2: Overwintering and the migration north from the colonies to Texas

The migration in 2018 was the best since 2006, and the conditions favoring population growth were probably the best since 2001. The weather conditions during the migration were excellent with abundant nectar along the entire migratory route. Texas, which experienced the rainiest September on record, was particularly rich with flowers and therefore nectar when the migration reached those latitudes in October. The last stages of the migration were delayed both in Texas and Mexico due to cold and rainy weather, and the monarchs first appeared at the overwintering sites about a week later than expected based on long-term records. Although the late fall and early winter conditions were said to be a bit warmer than usual, there were no events that appear to have contributed to higher than average winter mortality. In short, the monarchs wintered well. In March, or perhaps the last few days of February, monarchs began moving north toward Texas and the southern U.S. That return also went well with residents of Texas reporting a large number of first sightings to Journey North in March and April. At this point, I’m going to digress into a series of comparisons of the conditions during each stage for both 2018 and 2019 to illustrate why I’m predicting a lower number for the winter population in 2019-2020.

Stage 3: Reproduction by returning migrants in March and April in Texas and the South Region

Although the conditions (temperature and soil moisture) were favorable for population growth during March and April of both years, those for 2018 were better. Due to a dip in the jet stream in late March and early April, most egg laying was confined to Texas in 2018 due to the colder temperatures in North Texas and Oklahoma. Confinement to Texas resulted in a more optimal egg distribution in that it allowed a large proportion of the offspring of returning migrants to mature rapidly due to the warmer than normal March temperatures. I consider this scenario to be more optimal than having eggs distributed further north in March and early April since eggs laid at more northerly latitudes take longer to develop due to cooler temperatures. A basic principle in population biology is that populations with the lowest mean age to first reproduction grow the fastest. Although egg distribution, as inferred from first sightings, was similar in 2019, the temperatures were substantially lower in the critical developmental period resulting in a higher mean age to first reproduction than in 2018. The number of returning monarchs was higher in 2019, and more eggs and larvae may have been produced. However, this advantage could have been offset due to higher levels of fire ant predation since fire ant numbers increase following periods of abundant rainfall.

Stage 4: Migration of first-generation monarchs northward from late April to 10 June

The metric used to represent what happens during this stage is the number of days in May with temperatures above 70°F. Temperatures in this range appear to be associated with flights to the north/northeast and, using this metric, the temperatures in May allowed the population in 2018 to advance into the summer breeding area north of 40°N 7–10 days earlier than in 2019. That said, recolonization in 2019 was quite good with especially high numbers of first sightings reported to Journey North in the north central region (Michigan, Ohio, Ontario). The overall pattern of first sightings for the two years through early June is quite similar. Although the first sightings give us a picture of when monarchs reach each latitude, they don’t tell us the number of monarchs arriving at the northern latitudes. Lack of knowledge of the numbers of first-generation monarchs reaching each latitude or region limits how accurately we can predict growth of the population in June. The determinants of population growth in the northern breeding area are the time of arrival, the numbers arriving and the conditions that allow for an optimal number of hours of oviposition and larval growth. While I can’t compare the numbers arriving in the northern breeding areas in 2018 vs 2019, it does appear that the temperatures during the first two weeks in June in 2018 in the Upper Midwest were more favorable for population growth.

Stage 5: Population growth north of 40 N during June-August

The summer temperatures being 2°F higher than average in 2018 were more favorable for population growth than in 2019. In addition, the growth of the population appeared to be more widespread in 2018. In the Midwest, the highest production seemed to occur from 43–46°N in 2019 with lower than expected production from 40-43°N. From the Midwest, good production extended all the way to Maine including Ontario and parts of Quebec. Monarch numbers appeared to be higher in the Northeast in 2019 than in 2018. Comparing the size of the last generation for these two years has been difficult. While there were numerous reports of “best ever in the last xx years” there were also areas such as Iowa where the population was said to be low. Further, there was total silence about the size of the population from central Minnesota to 100°W in the central Dakotas, normally an area that produced high numbers of monarchs. I followed the number of roosts reported to Journey North almost daily for a clue as to the size of the fall population. The number of roosts were similar, but those of 2019 averaged smaller. Was that meaningful? There are many things that determine roost formation, their size and the probability that they would be observed. After wading through these mixed signals, I finally decided that the last generation and migratory population this fall was lower than in 2018 by perhaps 0.5–0.7 hectares.

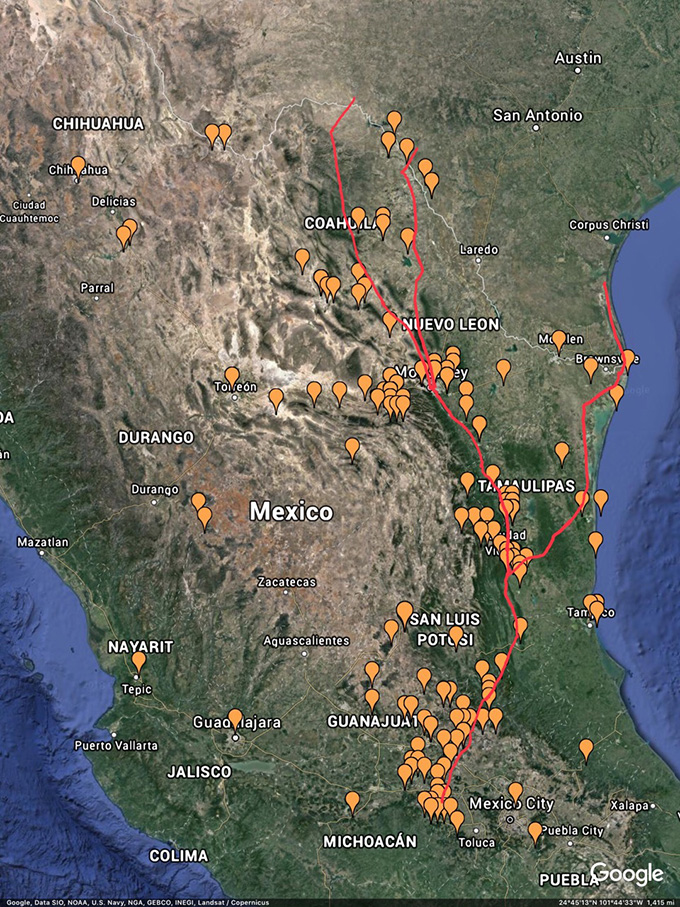

Stage 6: The fall migration from early August at 50°N in Canada to 19.5°N in Mexico

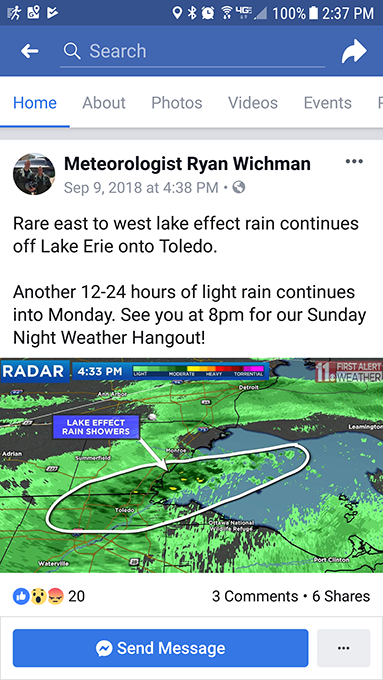

The migration typically starts out slowly in the north, often moves a bit more rapidly at mid latitudes and then slows down again as it moves through northeast Mexico to the overwintering sites. It’s usually the case that, as the migration reaches each latitude, there is a wave of monarchs with large numbers the first few days or perhaps a week with monarchs still passing through for the next two to three weeks. I often characterize the migration as a standing wave with a leading crest and a long tail of perhaps 28–30 days as it progresses southward across the latitudes. This year was different. The migration was extremely slow and appeared to be stalled in southern Minnesota and Iowa day after day. We hold our Monarch Watch tagging event at a time that aligns with the peak migration at this latitude year after year. There were virtually no monarchs at the time of our event this year (21 September). They were late and didn’t arrive in our area until the last few days of September—at least two weeks late. And then, what little we saw of the migration blew through the area in a week. If I were to judge the total migration on the basis of what we were aware of passing through Lawrence, I would have to say that this migration was the smallest and weakest I’ve seen since 1992 when we started Monarch Watch. Once the migration moved through our area, it continued to progress south/southwest at a moderate pace with masses evidently moving with a weather front that passed through Oklahoma City on the 5th of October. Again, about 17 days late for that latitude. Monarchs eventually reached Texas without much fanfare about roosts, masses seen, etc. and they seemed to pass through quickly.

In summary, this migration was extremely late. The migratory population also appeared to be compressed with the majority of butterflies moving through each latitude in a matter of days with fewer lagging monarchs than seen in most years. This pattern gives rise to at least two questions: 1) what was the cause of the delay? and 2) what impact will a late migration have on the total number of monarchs reaching the overwintering sites?

The lateness can be accounted for by the higher than average temperatures over a wide area of the Midwest in September and October. Although not precisely determined, we can infer from past migrations that the optimal temperatures for migratory flight range from the mid 60s to mid 70s on days when the winds are favorable. Those conditions were rare from southern Minnesota to southern Oklahoma in September and October. In Kansas and Oklahoma, temperatures for September were the second highest for the 125 years records have been kept. The lateness of this migration is a concern since late migrations are associated with lower numbers of monarchs reaching the overwintering sites.

Another concern is the drought in Texas. Droughts are also associated with lower numbers of monarchs reaching the overwintering sites. A question during this migration is whether monarchs suffered losses given that nectar was scarce in most of Texas south of the Dallas area. Nectar is needed to fuel flight and for monarchs to build up their fat bodies. Although we don’t know whether the population suffered significant losses as it passed through Texas, they appeared to move through the state rapidly. Fortunately, the temperatures in Texas were close to the long-term average over most of the migratory areas. These temperatures allow flight as opposed to high temperatures that tend to slow the migration.

I followed the temperatures and rainfall during most of September and October for northeastern Mexico. The bottom line is that the conditions (flowering, moisture and temperature) appear to be normal for this last leg of the migration.

Ok, let’s get back to the title—”Why overwintering monarch numbers will be lower this year”. Here is a quick summary in bullet points:

Population growth

• Less than optimal egg distribution in March and April

• Later recolonization of the Upper Midwest

• Low monarch production in Iowa and maybe western portions of the upper Midwest

• Lower summer temperatures than in 2018

Migration

• Late migrations are associated with lower numbers reaching Mexico

• Droughts are associated with lower numbers reaching Mexico

• High numbers in the northeast do not translate to high overwintering numbers

• Northeast butterflies are taking too long to migrate southwest

So, there you have it—my rationale for why the population will be lower this winter than in 2018. The number will surely be higher or lower than 4.7 hectares. I hope it’s higher, but I fear it will be lower. For the record, through July, based on an early reading of the data, I predicted a population of about 5 hectares that could trend higher if the summer temperatures were above average. They weren’t.

Filed under Monarch Population Status | Comments Off on Monarch Population Status