Jennie Brooks of Lawrence, Kansas: Her early contributions to monarch science

Saturday, April 20th, 2024 at 11:43 am by Chip TaylorFiled under General | Comments Off on Jennie Brooks of Lawrence, Kansas: Her early contributions to monarch science

by Chip Taylor, Founding Director, Monarch Watch

It is easy to forget how we came to know what is known today about monarchs. Our understandings of how the world works often have long and convoluted histories that include fundamental misunderstandings, unsupported interpretations and sometimes unintended consequences. These paths to discovery occur within a background of political history, prior knowledge, cultural biases and economic conditions – and so it was, and is, with monarchs.

Lincoln Brower detailed how we came to understand the migration and biology of the monarch in a 1995 paper entitled “Understanding and misunderstanding the migration of the monarch butterfly in North America, 1857-1995.” The story starts with the writings of naturalists and lepidopterists in the mid 1800s, the start of entomology as a science and later a period in which the public became interested in natural history. The account eventually leads to the recruitment of volunteers by Fred and Nora Urquhart to answer the question of where monarchs spend the winter – a quest that led to the “discovery” of overwintering sites in Mexico by Ken and Cathy (now Trail) Brugger. It’s a fascinating tale best understood if the reader reflects on the general state of knowledge in those times and the conditions of travel and communication. The pace of change was slower then.

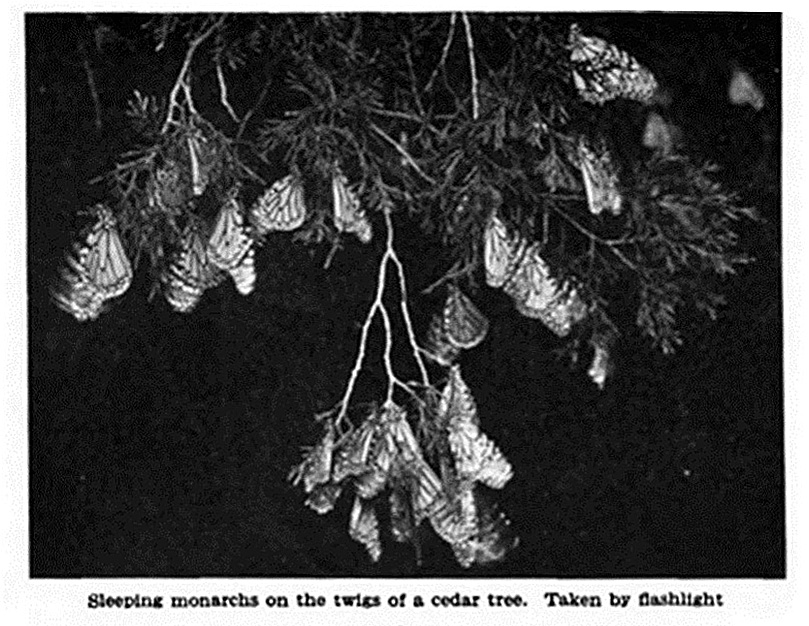

Although I knew much of the monarch backstory, I was surprised to learn from Brower’s text of Jennie Brooks, a Lawrence, Kansas resident, who in 1907, was the first person to publish a detailed description of the formation and breakup of an overnight monarch roost, the first to photograph a monarch cluster and the first to propose that monarchs overwintered in Mexico. I could relate. I knew Jennie’s neighborhood and having lived in Lawrence since 1969; I had seen many over-night monarch roosts. Having founded Monarch Watch in 1992, and after reading Brower’s article, I came to realize that in a sense I was following Jennie’s lead while validating her hypothesis with the aid of thousands of monarch taggers.

I was brought back to thinking about Jennie Brooks recently by Jeanne Klein, a retired KU professor, who volunteers as a Master Gardener at Monarch Watch’s Monarch Waystation #1. She researches and writes about Lawrence history and came across Jennie Brooks’ connection to monarchs and many natural history writings. Jeanne has written a long account about Jennie. The section that deals with monarchs is included here.

Jennie Brooks and Monarch Migrations in Lawrence, Kansas

by Jeanne Klein

Jennie Brooks (1853-1934), a part-time resident of Lawrence, Kansas from 1905 to 1910, was a devoted nature lover and prolific magazine writer. In mid-September 1906, she experienced a miraculous sight in the expansive front yard of her home at 1300 Haskell Ave. As she wrote, “I had been only three days in Kansas, and, lo! a migration of butterflies.” From 4:00 p.m. until after 6:00 p.m., she observed, described, and detailed swarms of monarch butterflies fluttering among milkweed plants and then hanging from the lower branches of elm, maple, spruce, and pine trees in the yard. Having decided to spend the night outdoors, she continued to study the monarchs’ behaviors and, at dawn, saw “fully two thousand wings [rise up] through the highest treetops, to the south—to the south! . . . [and all the way] to Mexico.” In this way, Jennie Brooks became the first person to theorize that monarch butterflies migrate to Mexico, as detailed in her touted 1907 article, “A Night with the Butterflies.”1

As Lincoln B. Brower wrote in 1995, her essay “was the first detailed description of the monarch’s clustering behavior during the fall migration. She combined elegant prose, high quality observation, counts of monarchs in the cluster, and actual experimental manipulation. No one before or since has so fully documented watching the quiescent monarchs all night long, their reaction to the rising sun, cluster break-up, and resumption of the southward migration.”2 Mrs. Maria Martin, her African American domestic servant, also witnessed this migration with Miss Brooks and declared, “‘Dat ain’t nothin’ new, Missy! I dun seed ’em a power o’ times swingin’ in de trees by de run!”3

Thrilled by her experience, Brooks consulted Francis H. Snow, a long-time professor of natural history and former chancellor of the University of Kansas. She astonished him by bringing him two monarchs. Back in 1875, Snow had catalogued 77 species of butterflies found in Douglas County, although apparently, he had not located nor listed monarchs by their Latin name, Anosia (now Danaus) plexippus, in the Nymphalidae family. He did however find their look alike mimic, the Archippus or Viceroy butterfly, that also feeds on milkweed plants.4 To satiate her demand for more knowledge, Snow and his biology students supplied Brooks with numerous books, including one by Samuel H. Scudder, who had named and described monarchs in 1875.5

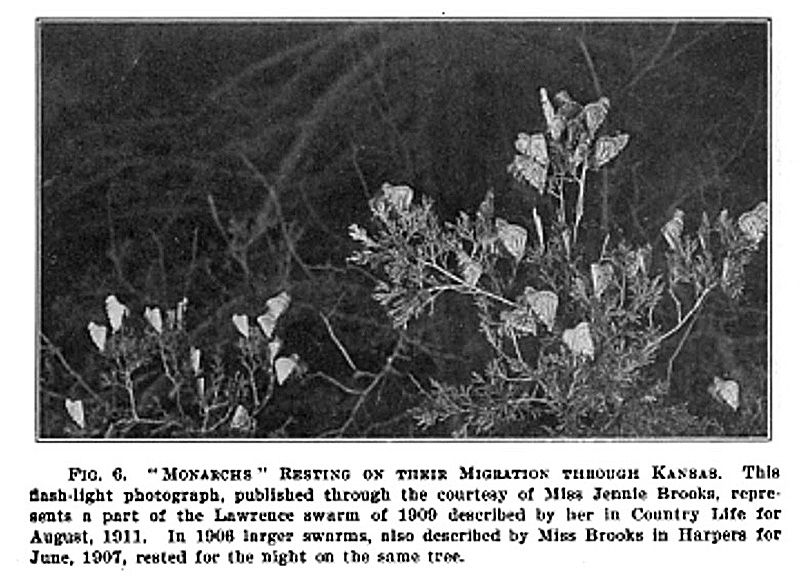

Three years later, Brooks’ brief sketch, “A Butterfly Flitting,” recounted a second migration of monarchs in her yard in mid-September 1909. By regarding them as “distinguished visitors,” she considered their selection of her cedar tree “a mark of special favor.” Again, she included photographs taken at night with her Kodak camera and a flashlight on the same cedar (Eastern juniper) tree.6

Jennie Brooks’ unique discoveries about monarchs’ fall migrations and her detailed accounts of their behaviors in Lawrence, Kansas deserve to be more widely known and credited by Monarch Watch enthusiasts across North America and Mexico. Each time you see a flitting monarch butterfly in the fall, remember Jennie Brooks and imagine monarchs’ extraordinary migrations “to the south—to the south!”

© Jeanne Klein 2024

Footnotes

1. Quoted in “A Night with the Butterflies,” Harper’s Monthly June 1907: 108-11. This article is available online in her book, Under Oxford Trees (Cincinnati: Jennings and Graham, 1911), at archive.org/ details/underoxfordtrees00broo/page/10/mode/2up.

2. Quoted in Lincoln B. Brower, “Understanding and Misunderstanding the Migration of the Monarch Butterfly (Nymphalidae) in North America, 1857-1995,” Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 49(4), 1995: 312.

3. Quoted in Jennie Brooks, “Migration Among the Butterflies,” Western Christian Advocate, June 5, 1912: 14, her third article on monarchs.

4. F. H. Snow, “Catalogue of the Lepidoptera [butterflies and moths] of Eastern Kansas,” Transactions of Kansas Academy of Science 4 (1875), 29-63. The Dyche Museum of Natural History does have one of Snow’s monarch specimens (#1561197) in its entomology collection found in the county with no date. The mention of milkweeds as a host for the viceroy is incorrect. The larvae feed on willows and cottonwoods.

5. In her 1907 article, Brooks quoted from Scudder’s Frail Children of the Air: Excursions Into the World of Butterflies (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1895), 53-55. Carl Linnaeus, the first author to consistently use binomial nomenclature, described the monarch in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae in 1758.

6. “A Butterfly Flitting,” Country Life in America, August 1, 1911, 48. Her second photograph was published in Howard J. Shannon, “Insect Migrations as Related to Those of Birds,” Scientific Monthly 3(3) (Sept., 1916): 238. Note that this photograph was published upside down. The Lawrence World (January 30, 1909) reported that Brooks discussed “The Butterflies” for the local Review Club, “which appeared in a recent McClure’s Magazine,” but this article has not been found.

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.