Monarch Population Dynamics: Issues of scale

Friday, June 28th, 2024 at 9:23 am by Chip TaylorFiled under Monarch Population Dynamics | Comments Off on Monarch Population Dynamics: Issues of scale

By Chip Taylor and John Pleasants

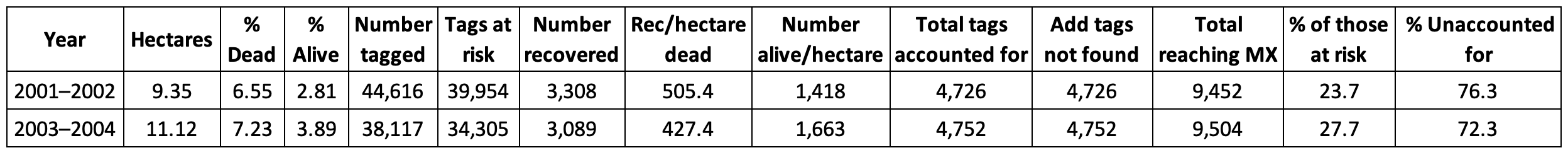

How big is the monarch population at the end of each breeding season? How many monarchs initiate the migration and how many successfully reach the overwintering sites in Mexico? The truth is, we don’t know the answer to these questions. To answer them, we need data. In this case, we only have the number tagged each fall and the number of tags recovered in Mexico and the estimate of the areas of forest occupied by monarchs in Mexico. Although the fact that the number tagged over the years is correlated with the size of the overwintering population (Taylor, et al, 2020) is helpful, it doesn’t tell us how many died during the migration. The proportion of those tagged that are recovered is only about 1% for all regions for all years, but the recovery rates based on latitude and longitude indicate that reaching Mexico is also a function of the flyway taken and the timing relative to the start of the migration. Size and sex are also factors (Taylor, et al, in prep). It’s complicated, but it is clear that mortality during the migration is substantial. What is needed is a fourth metric, specifically an estimate of the number of monarchs that died during the winter. There are two such data points in the record (Brower, et al, 2004) (Taylor, personal observations). Winter storms, the first in January 2002 and the combined storms in January and February 2004, killed an estimated 70% of the wintering population in 2002 and 65% in 2004. Both events yielded over 3000 recoveries (Table 1). These numbers have been used to calculate an average number of tags per hectare among the dead and remaining live monarchs. The number tagged was adjusted to account for handling mortality and the loss of tags due to improper placement. The new number represents the “tags at risk” (Table 1). Other adjustments were made to estimate the number that died but whose tags were not found. These combinations of known mortality and estimated deaths were used to estimate the numbers of monarchs that died during each of these migrations.

Table 1. Estimated mortality during monarch migrations based on the recovery of tags from monarchs killed during winter storms in early 2002 and 2004. The number tagged was reduced by 10% on the assumption that 5% of the tags are lost due to improper placement and another 5% are lost due to handling. Since not all tags are recovered due to off-site mortality and failure to find tags among the masses of dead monarchs, the tags not found was estimated to equal the number found. To calculate the number of tagged monarchs that reached the overwintering sites, the known number of tags in Mexico was added to the estimated number not found. That number represents the percentage of the tags at risk that reached Mexico, and the converse represents the percentage that failed to do so.

The goal of this exercise is to come up with a reasonable estimate of the total number of tagged monarchs that actually arrived at the overwintering sites. To reach this number, I made estimates of things that probably happen at some frequency but for which I have no direct evidence. For example, the tagging itself probably has a cost, to be safe, I have used an estimate of 5%. Similarly, I’ve estimated that 5% of the tags fall off during the migration due to improper placement. Those two estimates reduce the number of tags at risk (meaning available to reach Mexico). Those estimates are probably high, but the “at risk” number, being lower, favors a lower mortality percentage at the end of the calculation. In other words, this is a conservative estimate with respect to the number unaccounted for.

Assuming that all tags from dead monarchs are recovered is unrealistic. Some tagged monarchs die well away from the colonies, while on “streaming” flights in search of water. It is also unreasonable to expect those searching for tags to find all of them among the millions of dead butterflies that characterized these catastrophic events. Further, some sites were certainly searched more thoroughly than others. Those estimates are added to the tags accounted for to arrive at an estimate of the total number of tagged monarchs that reached the overwintering sites. Those totals, divided by the totals at risk, indicate that only 23.7 and 27.7% of the monarchs tagged in those seasons reached Mexico. In other, words 76.3 and 72.3% of the tagged monarchs are unaccounted for and presumably died, became lost or dropped out of the migration (Table1).

In summary, overestimations of tags that fall off, losses due to handling or tags not found at the overwintering sites, would suggest that mortality during the migration is higher than suggested in these calculations. Conversely, any estimation that indicates that more monarchs reached the overwintering sites than shown here, would lower the estimated mortality suggested in this treatment.

There is another way to estimate mortality that occurs during migrations. John Pleasants and I have discussed this issue several times. Here is John’s approach.

“In 2001 and 2003, 4.4% and 4.3% of tags were recovered. Let’s round to 5%. If we add in the estimate of tagged butterflies that are still alive, that brings the total accounted for to 7.7%. Let’s round to 8%. If 8% actually represents the minimum proportion of monarchs that make it to Mexico, that would mean that 92% failed to do so. It would also mean that every hectare with 20million monarchs represented the survivors of 250million that started the migration. Since overwintering number have averaged close to 3 hectares over the last 6 years, that would mean that roughly 750million monarchs head for Mexico each year.

However, 8% migration success is certainly an underestimate. Not all tagged monarch that die in Mexico are recovered. It’s likely that many die in areas that are not searched by local residents, and in a mass mortality year, with millions of butterflies to wade through the number of tags not recovered may be even greater. So, let’s double the 8% to 16% and round that up to 20% to make the calculations easier. That would mean that for every hectare of 20million butterflies, 100million started the journey. For an average year of 3 hectares that would be 300million starting the journey. In plain terms, 4 out of 5 monarchs fail to reach the overwintering sites.”

So, why is it important to understand the scale of the monarch population and the size of the migration? First, because the population on the move each fall, though it might be smaller than in the past when more habitat was available, is still quite large and it’s appropriate to ask what the human threats are to this population. Are they of a scale that requires that human contact with monarchs has to be regulated? The title for this text could have been Monarch Population Biology: Myths and Exaggerations. Without any data defining the scale of human activities or data on negative effects due to those activities, we have been told not to plant certain milkweeds because they will cause monarchs to break diapause and not migrate, or if raised on them they will not migrate. Neither are true. Tags from monarchs reared on the target milkweeds have been collected in Mexico. We are warned that rearing will lead to inbreeding and a weakening of the population. Given that rearing involves 1-2 generations for most who rear monarchs and that females mate multiple times such that serial paternity is the dominant form of reproduction, that’s nonsense. Selection works. It eliminates the unfit. We also hear that breeding will promote the propagation of the protozoan disease, O.e., that kills many emerging pupae, weakens adults and reduces their chance of surviving the migration. On this point, there is data that O.e. has negative effects (Majewska, et al, 2022), but the assumption that rearing leads to the release of a large number of O.e. infected and infested adults is unsupported by data. Many who rear monarchs claim they go to significant lengths to eliminate O.e. It’s not difficult. In the wild, the incidence of O.e. is the function of frequency and density-dependent interactions between monarchs and milkweeds that vary spatially and temporally (Taylor, 2022). To me, these are non-problems, or small-scale issues that can be managed. Regulation of human activities with respect to monarchs makes absolutely no sense. It’s a scale issue.

Human activities, other than habitat destruction, are trivial relative to the size of the migratory population. To make that point, let’s visit some of John’s numbers. We know that about 80,000 wild and reared butterflies are tagged each year. We don’t know the number reared and released but not tagged. The number is probably greater than 100,000 but how much greater is uncertain. For perspective, let’s assume the number is 220,000 which when added to the numbers tagged brings the total to 300,000. If 300 million is the average starting migratory population, 300,000 represents only 0.1% of the starting population. Insignificant indeed, even if all 300,000 died.

The big problem in monarch conservation is habitat loss (see refs in Taylor, 2024). We are losing grasslands at a rate of about a million acres a year and other land-use changes involving the growth of cities may also involve a million acres. Although milkweed restoration is underway on many fronts, there are no indications these efforts come close to matching the annual losses (Taylor, 2024).

The three r’s are critical in the evaluation of the status of species being considered for listing (Taylor, 2023). To avoid listing, data are required to show that a species is “resilient”, that is being able to recover rapidly from low numbers; “redundant” which refers to the ability to recover from catastrophic mortality and show “representation” which reflects both the role in the community and the ability to adapt to new conditions. There is ample data showing that monarchs are resilient, redundant, and adaptive. The monarch fits these criteria and no justification has emerged in the literature or in public discussions for listing the monarch as endangered or threatened. Those who study monarchs have not been consulted. A vast literature on monarchs has appeared in the last 4-5 years. We know more now about how the population functions from some of these publications and other writings, but this literature also contains a number of publications that promote interpretations based on an inadequate understanding of monarch biology. It would indeed be unfortunate if the status of monarchs were based on the interpretations in some of these publications.

There seems to be an implicit assumption that listing monarchs as threatened will benefit monarch conservation, but no path forward has been defined. There are no assurances that congress will provide funds for habitat restoration. Further, there seems to be no recognition that, within the habitat available. the year-to-year size of the eastern monarch population is determined by weather – which is most certainly independent of and unresponsive to regulations. Putting government regulations between monarchs and those who advocate for this species seems more likely to have a negative rather than positive impact on monarch conservation.

References

Brower, et al, 2004. Catastrophic winter storm mortality of monarch butterflies in Mexico during January 2002. In K.S. Oberhauser and M.J. Solensky, eds., The monarch butterfly: Biology and conservation, pp151-166. Ithaca.

Majewska, A. A., Davis, A. K., Altizer, S. & de Roode, J. C. (2022). Parasite dynamics in North American monarchs predicted by host density and seasonal migratory culling. Journal of Animal Ecology, 91, 780–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13678

Taylor, O.R. Jr., Pleasants. J.M., Grundel, R., Pecoraro, S.D., Lovett, J.P. and A. Ryan. 2020. Evaluating the Migration Mortality Hypothesis Using Monarch Tagging Data. Front. Ecol. Evol. 8:264. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.00264

Taylor, O.R. 2022. Monarchs, milkweeds and O. e.: It’s time for a more holistic approach. Monarch Watch Blog. https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2022/04/19/monarchs-milkweeds-and-o-e-its-time-for-a-more-holistic-approach

Taylor, O.R. 2023. Species Status Assessment and the three r’s. Monarch Watch Blog.

https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2023/10/13/species-status-assessment-and-the-three-rs

Taylor, O.R., 2024. Is the eastern monarch population continuing to decline? Monarch Watch Blog. https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2024/03/29/is-the-eastern-monarch-population-continuing-to-decline

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.