Monarch anatomy, life cycle, sensory systems, systematics, predation, and parasite control. |

||||||

MONARCH ANATOMY |

||||||

|

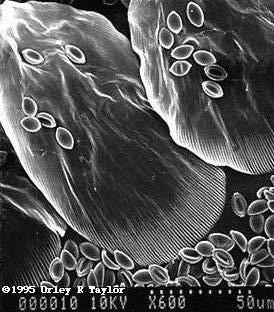

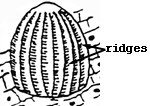

EGG Each butterfly egg is surrounded by a hard outer shell, called the chorion, to protect the developing larva. The shell is lined with a layer of wax, which helps keep the egg from drying out. Each egg has one to many tiny funnel-shaped openings at one end, called micropyles. Since eggs get their hard shell before they are fertilized, this hole, which penetrates all the way through the shell, allows sperm to enter. The raised areas on an egg shell are called ridges. They are formed inside the female before she lays the egg. Butterfly and moth eggs vary greatly in shape.

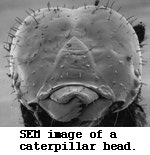

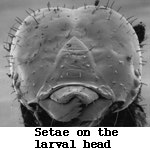

Larvae have three distinct body parts: head, thorax and abdomen. The head has a pair of very short antennae, mouthparts (upper lip, mandibles, and lower lip), and six pairs of very simple eyes, called ocelli. Even with all of these eyes, the caterpillar's vision is poor. The antennae help to guide the weak-eyed caterpillar and the maxillary palps, which are sensory organs, help direct food into the larva's jaws. Each thoracic segment has a pair of jointed, or true legs, while some of the abdominal segments have false legs, or prolegs. There are usually five pairs of prolegs. The prolegs have tiny hooks on them that hold the larva onto its silk mat or leaf. The fleshy tentacles at the front and rear ends of Monarch larvae are not antennae, but they do function as sense organs. Like other insects, Monarchs obtain oxygen through holes in the sides of their thorax and abdomen called spiracles. The spiracles are connected to a network of long airtubes called tracheae, which carry oxygen throughout the body.   Use the diagram on the left to identify the ocelli, mandibles and head capsule in the photo on the right.

When it pupates, a Monarch larva splits its exoskeleton and wiggles out of its larval skin. When this skin moves far enough down the body, the cremaster appears. The cremaster is a spiny appendage at the end of the abdomen. The Monarch hooks its cremaster into a silk pad spun by the larva just before pupation; it will hang from this until it emerges as an adult. The freshly exposed pupa is very soft and delicate until it hardens. You can see many different body parts on the pupa, including the wings, abdomen, legs and eyes.

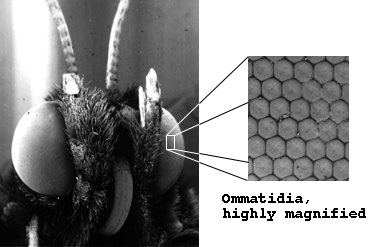

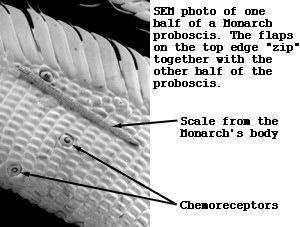

A butterfly's relatively enormous compound eyes are made up of thousands of ommatidia each of which senses light and images. The two antennae and the two palpi, which are densely covered with scales, sense molecules in the air and gives butterflies a sense of smell. The straw-like proboscis is the butterfly's tongue, through which it sucks nectar and water for nourishment. When not in use, the butterfly curls up its proboscis.   Three segments make up the thorax. Each segment has a pair of legs attached to it, while the second and third segments each have a pair of wings attached as well. The legs consist of six segments. They end in tarsi (singular, tarsus), which grip vegetation and flowers when the butterfly lands on a plant. Organs on the back of the tarsus "taste" sweet liquids. Monarchs (and other nymphalid butterflies) look like they only have four legs because the two front legs are tiny and curl up next to the thorax.

All butterflies and moths have four wings, two hindwings and two forewings. Small structures attach the wings to the thorax, and muscles attached to these structures move the wings. The butterfly can also move its wings by changing the shape of its thorax. Wing veins, tubes with thickened walls, contain trachea, nerves, and space for hemolymph to move through. Veins give the wings structure, strength, and support. The abdomen consists of eleven segments, the last two or three of which are joined. On male Monarch butterflies you can see a pair of claspers on the end of the abdomen. These appendages grasp the female during mating. |

||||||

SEXING MONARCHS |

||||||

|

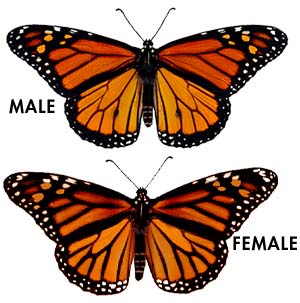

Sex determination in monarchs (and most butterflies and moths) occurs at fertilization of the egg. LARVAE The sex of monarch larvae can be determined only in dissection. Males will have undeveloped testes located in the 6th abdominal segment, dorsal to the gut. If you have a last instar male caterpillar, the testes will appear as two bright red or pink sacs; often they appear to be one sac. PUPAE To determine the sex of pupae requires only keen eyes or a dissecting microscope. Surrounding the cremaster (the structure from which the pupa hangs) are a series of rings, called abdominal sternites. Within the first ring (9th abdominal sternite) are several paired black dots next to the cremaster; turn the pupa so that you are looking at these dots. If the monarch is a female, the ring adjacent to the 9th sternite will have a line dissecting it; this line (indicated by the arrows on the photo and diagram below) will be centered between the pairs of dots. Male monarch pupae do not have this line.   Diagram modified from: Hughes, P. R., C. D. Radke, and J. A. A. Renwick. 1993. A Simple, Low-Input Method for Continuous Laboratory Rearing of the Monarch Butterfly (Lepidoptera: Danaidae) for Research. American Entomologist 39: 109-111. ADULTS

Female Monarch: Notice the thick vein pigmentation and no hindwing pouches. |

||||||

MONARCH LIFE CYCLE |

||||||

|

All insects change in form as they grow; this process is called metamorphosis. There are two kinds of metamorphosis, incomplete (or simple) metamorphosis, and complete metamorphosis. An example of incomplete metamorphosis is found in grasshoppers. The young nymphs usually look much like small wingless adults. The wings develop externally, and there is no prolonged immobile (pupal) stage. Butterflies and moths undergo complete metamorphosis, in which there are four distinct stages: egg, larva (caterpillar), pupa, and adult. Monarch development from egg to adult is completed in about 30 days.

Monarchs usually lay a single egg on a plant, often on the bottom of a leaf near the top of the plant. It is difficult to tell just how many eggs each female lays during her life, but the average is probably from 100 to 300. The eggs hatch about four days after they are laid. Approximate dimensions: 1.2mm high; 0.9mm wide

It is during this stage that Monarchs do all of their growing. They begin life by eating their eggshell, and then move on to the plant on which they were laid. When the caterpillar has become too large for its skin, it molts, or sheds its skin. At first, the new skin is very soft, and provides little support or protection. The new skin soon hardens and molds itself to the caterpillar, which often eats the shed skin before starting in anew on plant food! The intervals between molts are called instars. Monarchs go through five instars (see photo). Approximate length of body at each stage: 1st instar, 2-6mm; 2nd instar, 6-9mm; 3rd instar, 10-14mm; 4th instar, 13-25mm; 5th instar, 25-45mm.

During the pupal stage the transformation from larva to adult is completed. Pupae are much less mobile than larvae or adults, but in some lepidopteran species they make sudden movements if they are disturbed. Like other butterflies, Monarch pupae are well-camouflaged, since they have no other means of defense against predators.

The primary job of the adult stage is to reproduce - to mate and lay the eggs that will become the next generation. Females begin laying eggs right after their first mating, and both sexes will mate several times during their lives. Adults in summer generations live from two to five weeks. Each year, the final generation of Monarchs, which emerges in late summer and early fall, has an additional job: to migrate to their overwintering grounds, either in central Mexico for eastern Monarchs or in California for western Monarchs. Here they survive the long winter until conditions in the United States allow them to return to reproduce. These adults can live up to eight or nine months. Male and female Monarchs can be distinguished easily. Males have a black spot (see photo) on a vein on each hind wing that is not present on the female. These spots are made of specialized scales which produce a chemical used during courtship in many species of butterflies and moths, although such a chemical does not seem to be important in Monarch courtship. The ends of the abdomens are also different in males and females, and females often look darker than males and have wider veins on their wings. No growth occurs in the adult stage, but Monarchs need to obtain nourishment to maintain their body and fuel it for flight. Nectar from flowers, which is about 20% sugar, provides most of their adult food. Monarchs are not very picky about the source of their nectar, and will visit many different flowers. They use their vision to find flowers, but once they land on a potential food source, they use taste receptors on their feet to find the nectar. |

||||||

MONARCH SENSORY SYSTEMS |

||||||

|

Butterflies' sensory systems help them find food and mates, avoid predators, and choose appropriate host plants for their eggs. Their senses may be divided into four basic categories: touch, hearing, sight, and taste/smell. The last two categories are usually the most well-developed systems in butterflies. The information below introduces important organs associated with sensory systems at different life stages and explains how a butterfly uses its senses to navigate through its world. Butterfly sensory systems are very different from humans (for example, they can see ultraviolet light and hear ultrasound). These differences can make it hard to study butterfly senses. Butterflies probably use their senses in many ways we just don't know about yet because we perceive the world through mammalian senses.

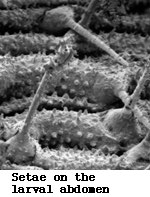

Touch is important in different ways during the larval and adult stages of a butterfly's life. They sense touch through hairs that extend through sockets in the exoskeleton. These hairs, called tactile setae, are attached to nerve cells, which relay information about the hairs' movement to the butterfly. In larvae, tactile setae are scattered fairly evenly over the whole body. You can see these setae on Monarch larvae with a simple magnifying lens or under a microscope. Larvae have a variety of responses to touch, and these responses may change over time. (This could be an interesting area of experimentation for students!) Many students notice that larvae often curl up into a ball when lightly touched.

HEARING. In general, butterflies appear to have poor hearing. Larvae perceive sound through tactile setae, but they seem to mainly respond to sudden noises. This is easy to observe in Monarch larvae, which will rear up if you clap loudly near them. This reaction is often called a startle response, a behavior that probably evolved to protect the larvae from predators who make noise. If you clap repeatedly, the butterflies get used to the noise and stop responding-a phenomenon of learning called habituation. Habituation happens throughout the animal kingdom, including in humans. For example, people who live in cities often stop noticing the noise of traffic until they go out into the country and "hear" its absence again. Adult butterflies often sense sound through veins in their wings, but scientists have only studied this in a limited number of species. A few species of moths and butterflies (not monarchs) make sound by rubbing or clicking together parts of their bodies (e.g., wing veins, legs, clapping their wings together, etc.). In some species this may be a means of communication between individuals and can play an important role in finding mates. In other species it seems to serve as a way to scare off predators such as birds. We're not sure how many species of butterflies and moths use sound because humans often can't hear the noises they produce. SIGHT. Butterflies see very differently during different stages of their lives. Larval vision is limited and poor. They see through their 12 ocelli, which have only a couple cells each (compared to the thousands of cells associated with adult insect eyes or human eyes). Larvae can still see the same range of light as adults, however, from red all the way through ultraviolet. Adults see through compound eyes made up of thousands of ommatidia. Each ommatidium gathers light and processes visual information through its own lens and nerve system.

The small plastic "Dragonfly eye" available in many science, toy, and photography stores can give students an idea of how the world looks through a compound eye. Compound eyes give butterflies excellent perception of color and motion in a wide range; butterflies can see up, down, forward, backward, and to the sides at the same time. On the other hand, they are not very good at judging distance or perceiving patterns, and the images are not united into one continuous picture. Butterflies apparently see the world as a series of still photos rather than a movie. Butterflies can also perceive polarized light (light waves that move in only one direction, and butterflies can sense that direction). Bees use their perception of polarized light to navigate to and from their hives, and some people suggest that butterflies may use it in similar ways, both to move around their habitat and to migrate.

Butterflies get much of their information about the world through chemoreceptors scattered across their bodies. In butterflies, chemoreceptors are nerve cells that open onto the surface of the exoskeleton and react to the presence of different chemicals in the environment. They operate on a system similar to a lock and key. When a particular chemical runs into a chemoreceptor, it fits into a "lock" on the nerve. This fit sends a message to the nerve cell telling the butterfly that it has encountered the chemical. For example, organs on the back of butterfly tarsi sense dissolved sugar; when the dissolved sugar touches these chemoreceptors, the butterfly extends its proboscis to eat the nectar its tarsi have sensed. Humans also have chemoreceptors, which are concentrated on the tongue (tastebuds) and in the nose.

Female butterflies often have important chemoreceptors on their legs to help them find appropriate host plants for their eggs. These chemoreceptors are at the base of spines on the back of the legs, and they run up along the spine to its tip. Females drum their legs against the plant, which releases plant juices. The chemoreceptors along the spines tell the butterfly whether they are standing on the correct host plant. Monarch females test host plants with all six legs before laying eggs. They also probably have chemoreceptors on their ovipositor. Monarchs invest a lot of time into finding the correct host plant for their eggs because it is essential for the eggs' survival. |

||||||

MONARCH SYSTEMATICS |

||||||

|

Systematics is the science of identifying, naming, and classifying living organisms into groups of related species. This process helps scientists not only communicate clearly about the species they study but also better understand and keep track of the millions of species that make up the natural world and the relationships of species to one another. BACKGROUND ON SYSTEMATICS Scientists name and put organisms into groups based on their evolutionary history (how closely related they are). These groups start very general and large, for example plants or animals, and become increasingly specific until you reach the name of just one species. Each species has a scientific name that anyone in the world can recognize, even in countries such as Russia or Japan where they use different alphabets. People have classified and named organisms for millennia (some systematists today, for example, study Native American names for plants as they work to classify new species). In the eighteenth century, a Swedish physician and botanist named Carolus Linneaus developed the naming system we use today. Using Latin and Greek words, Linneaus gave thousands of species two-part, or binomial, names based on characters such as their appearance or origin. The first part of a scientific name is called the genus. A genus includes one to many organisms that are closely related. The second part of a scientific name, called the species name, differentiates between members of a genus. Together, the genus and species name provide a unique name for every species. Some scientific names of familiar species are: Homo sapiens - human Notice that the scientific names of these species are printed in italics. (If you are handwriting a scientific name, you underline it.) You may want to show or read some of these names to your students. Scientific names are almost always descriptive. Using Latin or Greek, scientists name an organism for its appearance, its locality, its behavior, or to honor its discoverer. For example, Homo means human in Latin and sapiens means wise or knowing, also in Latin, so Homo sapiens refers to the wise humans. Octopus means eight feet and vulgaris means common. Biologists construct genealogies that represent their best understanding of the evolutionary relationships between species. To do this, they use specific traits called taxonomic characters. These characters are attributes that differ between groups and distinguish them from one another. Historically, taxonomic characters were most often traits such as form, shape, or structure of an organism's different parts. For example, taxonomic characters for a group of birds might include beak shape and size and wing shape. In Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), important traits include the shape of the genitalia and patterns of wing venation. Lepidoptera are divided into dozens of families. Generally, we think of these families in two groups: the butterflies and the moths. However, if we drew a "family tree" that accurately showed the evolutionary relationships between butterflies and other Lepidoptera, it would show that some moths are closer relatives of butterflies than of other moths. Butterflies are best described as a group of moths that has "escaped" being nocturnal and now is most active during the day. Butterflies and moths usually can be distinguished by the following traits. There are, however, some exceptions; for example, a few moths are active during the day and some butterflies have "fuzzy" bodies.

|

||||||

MONARCH PREDATION |

||||||

|

If female butterflies can produce 100 to 1000 eggs, why aren't there more butterflies in the world? Many factors play a part in controlling the size of butterfly populations, as they do for most living organisms. These factors fall into three main categories: (1) environmental conditions, including weather, space constraints, and food limitations; (2) accidents, including being crushed by cars, falling branches, or larger animals' feet; and (3) predation. Although all three of these play important roles in reducing natural populations, this section focuses on predation. Predation can be defined as an event in which one organism kills and consumes another organism or uses its nutrients without killing it. People often think of showy vertebrate predators first, such as lions chasing down a gazelle or birds feeding on butterflies they catch in mid-flight. But smaller invertebrate predators such as insects, spiders, bacteria, and viruses kill many more butterflies in most natural populations than do frogs, lizards, birds, toads, mice, and other vertebrates. Invertebrate predators also include parasites, organisms that take nutrients and resources from other organisms without killing them directly (although parasitism can result in death), and the specialized form of parasites called parasitoids, insects that consume other insects from the inside out. All butterflies have mechanisms that help protect them from predation. Some species are camouflaged: they either look like something else, such as a leaf or stick, or blend in with their backgrounds. Others have patterns that make them appear to be a bigger animal, such as eyespots on wings. Still other butterflies protect themselves through behavior. Adults can fly off, while larvae can live together in groups or drop to the ground suddenly if a predator approaches. Some butterflies also have mechanical or chemical defenses. Mechanical defenses are things like hairs, spines, or bristles that make it harder for the predator to get a good grasp on the larva, while chemical defenses make the butterfly less appetizing (maybe a noxious smell or a bad taste). Monarchs have an effective chemical defense. When they eat milkweed, they sequester the poisonous cardenolides (also called cardiac glycosides) in the milkweed. Cardenolides are poisonous to vertebrates (although maybe not to invertebrates, bacteria, and viruses), and most Monarchs face little predation from frogs, lizards, mice, birds, and other species with backbones. But being poisonous doesn't help the Monarchs after a predator has already killed and tried to eat them. Monarchs need some way to warn off predators before they become lunch. Monarchs do this through their warning coloration, or bright colors (yellow, orange, black, and white). This coloration warns potential predators that the animal contains poisonous chemicals. Warning coloration may work particularly well in adult butterflies because the hard body and wings allows a predator to bite the adult, taste the poison, and release the butterfly without killing it. It is common to see butterflies with beak-sized sections gone from their wings. Large wings help the butterfly escape relatively unharmed. Since Monarch wings contain distasteful cardenolides, one bite may discourage further attack without killing the adult. Early studies of Monarchs showed that when a blue jay ate a Monarch butterfly, it vomited shortly afterwards due to the cardenolides. That bird also learned to never eat another Monarch butterfly. Like this early study, most research about Monarch predation has focused on bird predation, especially on adults, and researchers have found a few species that eat Monarchs despite the cardenolides. However, invertebrates that eat the larvae are probably more important Monarch predators and thus play a more significant role in controlling Monarch population size. Despite their importance, scientists have done much less research on invertebrate predation of Monarchs. This is an important hole, since the cardenolides Monarchs sequester may not affect invertebrates in the same way. As you read about the studies of vertebrate predation on Monarchs, and about the little information we have on invertebrate predation, think about ways you might investigate the impact of invertebrate predators on Monarch butterfly populations. |

||||||

PREDATION AT OVERWINTERING SITES |

||||||

|

Scientists studying Monarch butterfly populations at their overwintering colonies (see the section on migration for more information about these sites) have discovered some interesting mouse and bird predators. These species have evolved ways to eat large quantities of adult Monarchs without being poisoned. In fact, the Monarchs seem to be an excellent food source for some of these species. The studies summarized below have investigated the details of predation as well as the impact it has on Monarch populations. Bird Predators In the mid-1970s, scientists discovered Monarch overwintering roosts in Mexico. As they began to study these roosts, they found extraordinarily high mortality due to predation. Although researchers had reported some predation in California Monarch roosts before this, such high levels of predation spurred a number of studies investigating the species that preyed upon the Monarchs, ways those species avoided poisoning, the patterns of predation, and the impact of predation on Monarch populations. Although many birds live in the same area as the Mexican roosts, only a few feed heavily on Monarchs. Of 37 bird species reported in the region, 25 never feed on Monarchs while another eight only rarely eat a Monarch. Two species, Scott's oriole and Stellar's jay, occasionally hunt Monarchs, which means that small numbers of birds visit the roosts irregularly to feed on Monarchs. The two remaining species, black-headed grosbeaks and black-backed orioles, are the main Monarch predators. These two species feed twice daily at the roosts in mixed flocks of five to at least 60 birds and annually consume several million Monarchs in the Mexican roosts. Black-headed grosbeaks and black-backed orioles have very different ways of avoiding poisoning when they eat Monarchs. Grosbeaks, which eat the entire Monarch abdomen, are relatively insensitive to cardenolides and can tolerate moderate levels of these chemicals in their digestive tract. Orioles, on the other hand, vomit after consuming much smaller amounts of cardenolides. They avoid poisoning by not eating the cuticle, which is where Monarchs store cardenolides. Orioles slit open the body and strip out the soft insides. Oriole and grosbeak predation follows several patterns. For example, grosbeaks eat fewer female Monarchs than orioles. Female Monarchs have, on average, 30% higher cardenolide concentrations than males. Females, therefore, may be more toxic than males. Since orioles avoid the cardenolide-laden cuticle, increasing concentrations may not affect them. On the other hand, females also contain more lipids (fats) than males and therefore may provide more nutrients per prey item than males. Scientists still have not determined the relative important of these two different forces (avoiding poisons and obtaining nutrients). Other characteristics may affect the amount of predation too. The edge or periphery of the roost faces higher levels of predation than the center. Thus, small roosts, with a larger edge to interior ratio, face higher overall predation than larger roosts, which have a lower edge to interior ratio. Forest thinning, due to natural causes such as streambeds or human-induced causes such as selective logging or brush clearing, also increases predation. Thinning increases the surface area of the roost and makes the top side of the roost more accessible to predators. Grosbeak and oriole predation causes more than 60% of Monarch mortality at many Mexican roosting sites, killing approximately 7 to 44% of the total population. At one 2.25 hectare colony, for example, birds ate an average of 15,000 butterflies daily and over 2 million for the season, which constituted 9% of the roost's population. Some scientists have speculated about the evolutionary impact of such high levels of predation. Since edges are more vulnerable to predation than interiors, Monarchs that overwinter in large colonies could be more likely to survive than those in smaller colonies; in large colonies, with their lower edge to interior ratio, a smaller percentage of the butterflies are vulnerable to edge predation. Early arrival at the roost would also be advantageous, since the center of the roost faces less predation risk than the edges. Avoiding predation could also be a force molding behaviors that help individuals regain a central position in the roost when they leave for water or nectar, or when they are blown down by storms. Mice Predators Five species of mice are known to be abundant near the Mexican overwintering roosts of Monarch butterflies. Of these five, only the scansorial black-eared mouse, Peromyscus melanotis, eats Monarchs. Several studies have investigated how P. melanotis avoids poisoning, the impact Monarch consumption has on the mouse, and the impact mouse predation has on the Monarch population. An individual P. melanotis consumes an average of 37 Monarchs each night. They feed preferentially on easily accessible butterflies (near the ground) and on "wet" butterflies (dead butterflies that have not dried out). During the winter season, P. melanotis migrate to Monarch roosts where they set up residence and breed intensively. The population of mice in Monarch roosts generally do better than other mice of the same species whose territories are outside of the roosts; mice in roosts are larger, heavier, and reproduce more than mice outside the roosts. They are the only mammalian species scientists have found that have overcome Monarch chemical defenses enough to effectively exploit the dependable food source Monarch roosts represent. Over the winter season, these mice may consume 4 to 5.7% of the total population of the Monarch colony. This translates into at least one million butterflies each winter in a 2.25 ha roost. This level of predation may also have helped mold Monarch behavior in winter roosts. For example, Monarchs generally crawl up vegetation. Moving up might help protect Monarchs from both freezing temperatures near the ground and from greater mouse predation. On a conservation note, this means that it is important to also protect the understory vegetation in winter roosts so that Monarchs can escape mouse predation more easily. |

||||||

PREDATION BY INVERTEBRATES, PARASITOIDS & DISEASE |

||||||

|

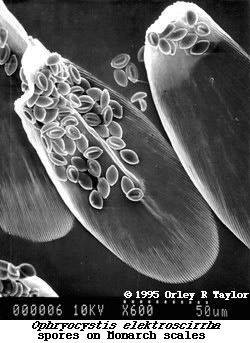

Although the larval stage is where most predation and death probably occur, few researchers have investigated this area. The sections below explore the anecdotal and rare experimental evidence about the impact of invertebrate predators, parasitoids, and pathogens on larvae and adults. Invertebrate Predation Very little ecological or evolutionary research has been done regarding invertebrate predation on Monarch butterflies, and most of the literature contains merely anecdotal evidence of predation events. For example, one group of scientists report a wasp attacking an adult Monarch butterfly in an overwinter California population. The wasp, Vespula vulgaris, fed on the butterfly's abdomen. Other naturalists and scientists have observed other wasps, ambush bugs, and stink bugs killing and consuming Monarch larvae, but these predators are not well studied. In a more comprehensive research program, a researcher at Cornell University is studying the impact of different levels of cardenolides and other poisons on wasp predation and consumption of various larvae. Her preliminary results suggest that some wasps are sensitive to chemical concentrations and may selectively hunt larvae with lower concentrations of poisons. Parasitoids Researchers and naturalists have observed a small number of species that are parasitoids on Monarch butterflies. Four species of tachinid flies lay their eggs on Monarch larvae. The tachinid larva burrows into a Monarch larva and eats tissues and fluid from the monarch's body. The Monarch larva lives and continues to grow until the tachinid larva is ready to leave. Then the fly larva kills its Monarch host. The following Monarch Watch Newsletter articles contain additional information, including photos: July 2003 & August 2003 Another occasional parasitoid is a braconid wasp. The female braconid lays one egg inside the Monarch larva. From that egg, as many as 32 adults develop. These 32 adults are genetically identical, just like identical twins in humans. Disease (Pathogens) Diseases are usually caused by organisms (called pathogens) that live inside other organisms, taking nutrients and other resources from the host. Pathogens can be fungi, bacteria, viruses, or single-celled organisms called protozoans. Can you think of organisms from each of these groups that affect humans? There has been no research on fungal infections of Monarchs, probably because none have been observed yet. This is interesting, since many Monarchs are raised in captivity for research and educational purposes. Most other species of butterflies raised in captivity are susceptible to fungal attacks. Anecdotal evidence also suggests that milkweed plants are resistant to fungi. Can you think of ways to test whether or not these two observations are related? Five bacterial pathogens have been reported for Monarchs. One of these is a psuedomonas that seems to only invade larvae already weakened by other disease. Other butterflies and moths are susceptible to bacillus bacteria, but this group of bacteria has not been observed in Monarchs. Nuclear polyhedrosis virus is probably the most important viral pathogen for Monarchs. Both larvae and pupae are vulnerable. This virus forms crystals inside infected cells, and the crystals kill the cells. The virus actually putrefies the insides of the infected individual. Infected Monarch larvae become lethargic, lose their bright yellow and white stripes, and turn light brown, then dark brown, then black. If you pick up an infected larva when it is black, it will break open and a foul-smelling black liquid will spill out. Monarch pupae infected with this virus turn from light green to yellow to black. The best-studied disease of Monarchs is the parasitic protozoan Ophryocystis elektroscirrha. The parasite develops inside the Monarch larva and pupa, and is transmitted from generation to generation by spores, which are shed from the scales of the adult female onto her eggs and the surface of milkweed plants as she lays eggs. The spores are also transferred between males and females during copulation (mating).

|

||||||

OPHRYOCYSTIS ELEKTROSCIRRHA |

||||||

|

This parasite develops inside the Monarch larva and pupa, and is transmitted from generation to generation by spores, which are shed from the scales of the adult female onto her eggs and the surface of milkweed plants as she lays eggs. The spores are also transferred between males and females during copulation (mating). Are there other means of spore transmission? This leads us to another important question, that is, how do the spores persist from year to year? Adult butterflies carrying the most spores, which they acquired as larvae, do not live as long as uninfested adults and few, if any, of these adults seem likely to survive the winter on the roost to carry the spore northward again in the spring. So, how does the spore persist in the population? One possibility is that spores are transmitted passively through close contact from infested to uninfested adults as they roost together during the migration. All the monarchs which had been infected as larvae might die during the winter but the spore could survive by adhering to scales on the wings and abdomen of otherwise healthy individuals.

These findings are consistent with the idea that this neogregarine parasite can persist from year to year through passive transmission of spores from infested individuals. However, more studies are needed. In particular, we need to know whether adults carrying spores which they acquired as larvae, actually survive the winter. We also need to establish the percentage of fall and spring migrants which bear spores and the "spore load" of the infested individuals. In Eastern monarch populations, the proportion of fall migrants with spores appears to be less than 5%. What should we expect from the spring migrants in terms of percentage infestation and average spore load? If you are trying to maintain a Monarch culture, there are steps that can be taken to control this parasite (see below). There are still many questions about infection levels during spring and fall migration, survivorship of infected adults during the winter, and how many spores infected adults in nature actually carry. Can you think of other questions about this parasite and its relationship to monarchs?

|

||||||

CONTROL OF OPHRYOCYSTIS ELEKTROSCIRRHA |

||||||

|

Many of us are distributing Monarch butterflies as a means to excite the public, especially schoolchildren, about the wonders of butterflies, metamorphosis and migration. Unfortunately, there is a good chance that our efforts may be actually harming Monarchs by increasing the frequency of an insidious parasite. We have experienced this parasite in our rearing operations at the Universities of Minnesota and Kansas, and know that we have inadvertently distributed larvae that may have been infected. Since most people that receive Monarchs release them, this is likely to result in a higher frequency of infected butterflies. We have been working for the past year on controlling this parasite, and would like to share our results with you in the hope of preventing further negative effects on an organism that we all view with a sense of awe and wonder. The parasite is a protozoan, with the Latin name of Ophryocystis elektroscirrha. It was first described over 20 years ago, but only began receiving a great deal of attention in the last several years. The parasite begins its life cycle as an inactive spore which needs to be eaten by a larva. It multiplies within the larva, and during the last few days of the pupal stage produces new spores that are on butterfly's scales when it emerges. It is then transferred to the surface of the egg or milkweed during oviposition, and begins a new cycle when it is eaten by the emerging larva. We have shown that the spores can be transferred from an infected male to a healthy female during mating, and that this female can transfer them to her offspring. Spores can also be transferred passively, when an infected butterfly is held in a cage with healthy butterflies (and probably also in the dense overwintering clusters in California and Mexico), although we have not yet learned whether this means of spore transfer results in infected offspring from an otherwise healthy female. You may have experienced this parasite. If you have noticed pupae with dark gray blotches on them just before you see the butterfly through the pupa covering, or if some of your butterflies fail to emerge completely and seem stuck within the pupa, it is probably because they are infected. This is more likely to happen if you rear more than one generation using the offspring from one generation as parents of the next, or if you use the same cages for several generations. However, these symptoms only appear with very high levels of infection, and your pupae and adults can appear perfectly normal and still be heavily infected. What should be done? We have worked out a way to control this parasite that we hope will not be too difficult. Our method requires cleaning up your rearing operation; we have not yet found a way to "cure" a larva once it has eaten the spores, although at the University of Kansas we are continuing to look for such a solution using drugs that have been shown to work on related organisms. We have had limited success with attempts to surface-decontaminate eggs once they have been laid, although this does lower the incidence of the disease. Thus, the only way to solve the problem, and to prevent more releases of contaminated butterflies, is to make sure that the larvae you rear are never exposed to the parasite. There are four steps you will need to take: 1. Clean all of your rearing cages and other equipment. It is difficult to clean wooden cages unless you have access to an autoclave. At Minnesota, we use wood and screen cages to rear larvae, and have successfully decontaminated them in an autoclave. If you use plastic cages, they can be decontaminated by soaking them in a 10% bleach solution (approximately 10 ml Chlorox bleach to 100 ml water) or 100% ethanol for at least 15 minutes, then rinsed well. Use the bleach solution to soak any tools that you use to transfer larvae, rinsing them after they are soaked. Wipe down countertops and other surfaces with the bleach solution in areas in which you have reared larvae or kept butterflies. The spores survive long periods of time (over a year), and can also survive freezing temperatures, so equipment that you used last year or left outside over the winter will still be able to infect larvae. 2. Check all females you use to produce eggs to make sure that they are not contaminated with spores. This is especially important if they have been reared in captivity, but wild females should also be checked. To look for spores, you will need a tweezers or forceps, clear scotch tape (not the "magic", slightly foggy kind), microscope slides, and access to a microscope. Your local high school, veterinary clinic, or the biology department of a university or college might have microscopes that you could use.

3. If your females have no spores, they can be used to obtain eggs. If you mate them, check the males too. 4. You should go through an entire generation before disseminating any larvae or pupae to people that might release them. This step is important if you have used your present equipment, or even rearing space, before, especially if you have experienced the symptoms described above. Since it is impossible to tell if a larva or pupa is infected without dissecting it, you should rear all of this generation to adulthood, and check the butterflies as soon as they can be handled. If fewer than 5 out of every 100 adults are infected, it should be safe to distribute larvae and pupae from the next generation. Be sure, however, to continue to follow steps 1 through 3. Infected butterflies should all be killed. It took us two generations to completely get rid of the disease. In Minnesota, we are continuing to study the disease, and purposely inoculate some eggs with spores so that we can learn more about how it is transmitted. Even though this requires that there are some spores around, by being very careful to keep infected stock away (this means in a different room) from healthy stock and sterilizing all equipment, we have experienced no infected individuals in uninoculated stock for two generations. We continue to check every butterfly that emerges for spores, however. We realize that this might seem burdensome and it seems cruel to kill butterflies that look perfectly healthy. We do not see an alternative, however, and believe that all of us share a common interest and responsibility to preserve the health of this amazing organism. |

All material on this site © Monarch Watch unless otherwise noted. Terms of use.

Monarch Watch (888) TAGGING - or - (785) 864-4441

monarch@ku.edu

LARVA

LARVA PUPA

PUPA ADULT

ADULT

Egg (3-4 days)

Egg (3-4 days) Larva (Caterpillar; 10-14 days)

Larva (Caterpillar; 10-14 days) Pupa (Chrysalis; 10-14 days)

Pupa (Chrysalis; 10-14 days) Adult

Adult TOUCH.

TOUCH. Adults have tactile setae on almost all of their body parts. In both adults and larvae, the setae play an important role in helping the butterfly sense the relative position of many body parts (e.g., where is the second segment of the thorax in relation to the third segment). This is especially important for flight, and there are several collections of specialized setae and nerves that help the adult sense wind, gravity, and the position of head, body, wings, legs, antennae, and other body parts. In monarchs, setae on the adult's antennae sense both touch and smell.

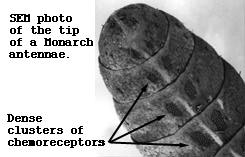

Adults have tactile setae on almost all of their body parts. In both adults and larvae, the setae play an important role in helping the butterfly sense the relative position of many body parts (e.g., where is the second segment of the thorax in relation to the third segment). This is especially important for flight, and there are several collections of specialized setae and nerves that help the adult sense wind, gravity, and the position of head, body, wings, legs, antennae, and other body parts. In monarchs, setae on the adult's antennae sense both touch and smell. TASTE & SMELL.

TASTE & SMELL. Adult butterflies sense most smells through their antennae, which are densely covered with chemoreceptors, especially on the clubs. In monarchs, chemoreceptors on the antennae sense the honey odor associated with nectar and feeding as well as special chemicals released by the male, called pheromones. In general, pheromones help males and females of the same species find each other to mate. Monarch males can produce pheromones, which they secrete through special glands on the wings. In contrast to their close relatives, however, monarchs do not require pheromones for successful mating. Scientists are still studying what role, if any, pheromones play in Monarch mating rituals.

Adult butterflies sense most smells through their antennae, which are densely covered with chemoreceptors, especially on the clubs. In monarchs, chemoreceptors on the antennae sense the honey odor associated with nectar and feeding as well as special chemicals released by the male, called pheromones. In general, pheromones help males and females of the same species find each other to mate. Monarch males can produce pheromones, which they secrete through special glands on the wings. In contrast to their close relatives, however, monarchs do not require pheromones for successful mating. Scientists are still studying what role, if any, pheromones play in Monarch mating rituals.

Students taking Chip Taylor's 1994 course in Experimental Field Ecology examined the possibility of passive transmission of Ophryocystis elektroscirrha spores. Sonia Altizer and Karen Oberhauser suggested that spores could be sampled by applying a strip of clear scotch tape to the abdomen to remove a thin layer of scales. The tape is applied to a slide and examined under a microscope at 100x for spores. The spores are counted in a 1cm squared box drawn on the area of the tape containing the scales. In the classroom study the infestation rate was quantified using a scale of zero to four, with zero being no spores and four being >1000. The students caught 12 wild males, each had an infestation level of zero. The males were housed in a 2 foot square cage with eight laboratory reared males all of which had infestation levels of four (thousands of spores). The cage was provided with "butterfly nectar" so the adults could self feed, and every three days, four of the wild-caught butterflies were sampled for spore infestation. This sampling continued until each wild-caught butterfly had been sampled twice or had died. The students found that 75% (8 out of 12) of the wild-caught butterflies became contaminated with spores. The results indicate passive transmission of the spores occurs through non-mating contact with other butterflies and with substrates where infested butterflies have been housed.

Students taking Chip Taylor's 1994 course in Experimental Field Ecology examined the possibility of passive transmission of Ophryocystis elektroscirrha spores. Sonia Altizer and Karen Oberhauser suggested that spores could be sampled by applying a strip of clear scotch tape to the abdomen to remove a thin layer of scales. The tape is applied to a slide and examined under a microscope at 100x for spores. The spores are counted in a 1cm squared box drawn on the area of the tape containing the scales. In the classroom study the infestation rate was quantified using a scale of zero to four, with zero being no spores and four being >1000. The students caught 12 wild males, each had an infestation level of zero. The males were housed in a 2 foot square cage with eight laboratory reared males all of which had infestation levels of four (thousands of spores). The cage was provided with "butterfly nectar" so the adults could self feed, and every three days, four of the wild-caught butterflies were sampled for spore infestation. This sampling continued until each wild-caught butterfly had been sampled twice or had died. The students found that 75% (8 out of 12) of the wild-caught butterflies became contaminated with spores. The results indicate passive transmission of the spores occurs through non-mating contact with other butterflies and with substrates where infested butterflies have been housed.